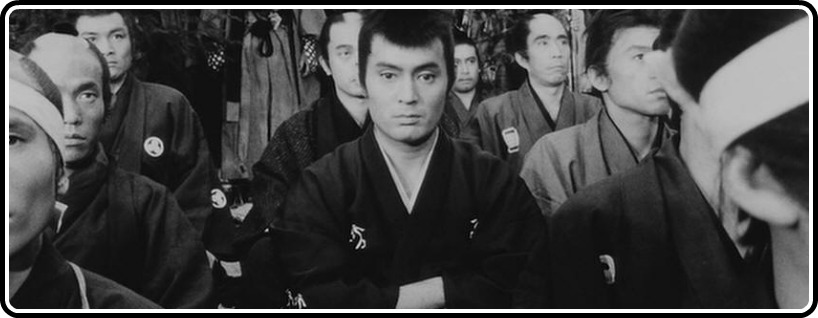

We open on a mountaintop. An elderly man (Kamatami Fujiwara) and his granddaughter (Yoko Naito) emerge. He tells her the Buddhist origins of the lands surrounding them. They stop to rest and eat their lunch before beginning their downhill descent. The granddaughter, whose name is Omatsu, goes to find water. The elderly man prays for death so that his granddaughter will be happy and ‘no longer a pilgrim’. Suddenly, a deep voice calls out ‘old man’. He turns around and sees a man in black garb, his hat covering his face, smoke all around him. He approaches the elderly man and tells him to step forward and look to the west. The elderly man realizes what is about to happen, but before he can elicit a response; he is struck down with his wish cruelly fulfilled. The murderer is a samurai named Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai), and he is The Sword of Doom‘s protagonist.

The Sword of Doom, a jidaigeki set in the tail end of the Edo period, follows the likely psychopathic Ryunosuke through several ‘˜incidents’. The first involves an upcoming duel with Bunnojo (Ichiro Nakatani). Bunnojo’s wife Ohama (Michiyo Aratama) goes to Ryunosuke begging him to lose the match because Bunnojo is so scared to face him. Ryunosuke agrees to if she gives up her chastity to him. She does, but Bunnojo ends up dead anyways. Outcast, the samurai now lives with Ohama (they also have a son) as a member of the Shinsengumi. It turns out Bunnojo’s brother Hyoma (Yuzo Kayama) has been training with a master swordsman (Toshiro Mifune in a rare supporting role) in order to exact revenge on his brother’s killer. We also follow Omatsu, the young woman from the film’s opening scene, as she tries to find her place in the world and makes a connection with Hyoma.

It is difficult to give a synopsis of The Sword of Doom because the film is, to a degree, open-ended. The source material is “Daibosatsu Tobe” (The Great Buddha Pass), a newspaper serial by author Kaizan Nakazato that ran for three decades. Many versions of the tale have been told, and it is presumably a very familiar story within Japanese culture. There were supposed to be sequels to Kihachi Okamoto’s adaptation, but they fell through, making The Sword of Doom forgivably scattered at times.

At the center of Okamoto’s standout samurai film is the great and legendary Tatsuya Nakadai, forever searing himself into the memories of all who watch The Sword of Doom. Ryunosuke seems at least partially convinced he is thrust into situations that force him to kill, and he does so with a sense of duty and fierce indifference. Nothing affects him; his eyes are glassy and empty but with the slightest hint of longing. He stares off into space, rarely the active participant in a conversation. His interactions with others suggest boredom. He waits for something to instigate a reaction; it is almost an unspoken challenge to everyone who speaks to him. He lives entirely in his own world, without feeling, remorse or connection.

Once Nakadai and director Okamoto get the concrete lifelessness of Ryunosuke across, the viewer’s fascination comes from seeing our protagonist slowly unhinge. Take Shimada’s (Mifune) swordfight in the snow and Ryunosuke’s reaction to the decimation of his associates. For the first time, we are seeing fear on Nakadai’s face. That fear emerges as he realizes he might have met his match in Shimada. That fear carries over into the next scene with Ohama, which Okamoto executes to marvelous effect. The camera is close to Ryunosuke, on his right, and we see that he is still very much shaken over Shimada’s swordsman skills. The emptiness in his eyes has been stirred and something frightened now lies behind them. The camera cuts to Ohama’s perspective, on his left and much farther away. It is clear that she cannot see any difference in his behavior, and from her point of view, it certainly looks like he is acting the way he always does. That first shot though, has shown us that he is not. We can see that Ohama is not failing to see what is in front of her face, because Ryunosuke’s internal dilemma truly is invisible from her point-of-view. Okamoto uses the camera to show how both Ryunosuke and Ohama perceive their conversation within the same scene.

Choreography becomes equivalent to performance art in The Sword of Doom. It is said throughout that Ryunosuke’s style of swordsmanship is very unorthodox; and it does not take an expert to see that. His stance and body language are off-putting and methodical; it is impossible predict what he is thinking, doubly so during a fight. He is alert yet slack and swift as a machine. My experience in this genre may be limited, but Ryunosuke’s style is unlike any samurai fighting I have seen. Several scenes show us how Ryunosuke fights, so we can compare said scenes to the final ten minutes.

The final ten minutes of The Sword of Doom are justifiably well-known to samurai film enthusiasts. It is gutsy and exhausting, showing a kind of physical representation of nihilism. Yes; this is what insanity looks like. Okamoto uses subtle theatrical techniques with lighting and space as Ryunosuke destroys everything in his path. Nakadai is entirely frightening here, and when I say this is a piece of performance art, I mean it. The use of choreography to represent psyche here is shockingly effective. Ryunosuke is haunted by his guilt as he slashes alternately at nothing and at dozens with uncontrolled precision. He stumbles with broad movements. How long can he last like this? This is a man truly unhinged. The Sword of Doom may leave us wanting the sequel we would never get, but in a way, it doesn’t get any more final than that concluding freeze-frame shot.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)