With the virtual avalanche of buzz and excitement surrounding this weekend’s release of The Avengers, I figured the best way for this column to tap into the frenzy (without adding yet another Avengers review to the ubiquitous coverage that film’s already generated) would be to find the best example of a popular superhero movie available within the Eclipse Series and talk about it here. Fortunately for me, I didn’t have to search too long or hard, since Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two, from Eclipse Series 23: The First Films of Akira Kurosawa was already in my sights. That’s because I just recently watched Kurosawa’s smash hit Sanjuro, from 1962, for my Criterion Reflections blog. What Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two and Sanjuro both have in common (besides protagonists with similar-sounding names) is that they’re both sequels that Kurosawa was pressured by his studios to make on short notice, in order to capitalize on the box office triumphs of their respective predecessors. The biggest difference between the two pairs comes from their positioning in Kurosawa’s filmography. The Sanshiro films were made when he was just getting started, filmed in the early 1940s when Japan was at war, and surviving only in a few rough prints that reveal a lot of wear and tear. Yojimbo/Sanjuro are accomplished masterworks that benefited from large studio budgets and the best talents in all phases of filmcraft available at the time, and they come to us in pristine condition.

In an illustrious career filled with monumentally revered films, innovative directorial techniques and impressive character archetypes, Kurosawa’s lasting influence on cinema is incalculable. Though later films like Seven Samurai and The Hidden Fortress are commonly regarded as forerunners of the summer blockbuster formula that now provides the foundation for the 21st century Hollywood movie industry, I think a case can be made that even his early achievements in creating well-received crowd pleasing follow-ups contributed meaningfully to the science that now goes into planning today’s lucrative fantasy franchises.

For a fuller introduction to the character and story arc of Sanshiro Sugata, follow that link to my review of Kurosawa’s debut film that I wrote a few months back in similar conjunction with my viewing of Yojimbo (the film Sanjuro built upon.) Or if you’re in a hurry, here’s a quick recap: In late 19th century Japan, various schools of martial arts are competing to recruit followers and demonstrate their superiority. Sanshiro is a rickshaw driver who’s originally drawn to practice jujitsu but converts over to the new technique of judo. Gifted with athletic prowess and impressive strength, he quickly acquires new fighting skills and proves to be unbeatable in competition. But he’s a brash young man who misuses his talent in street brawls and also causes severe injury to some of his opponents, making him a target for revenge. Even as he strives to tame his inner demons and achieve the mental tranquility that will make him a true master of judo, he’s pushed and provoked to fight one last showdown with his vicious rival. It’s the timeless set-up, a peaceful warrior beset by a hostile provocateur to the point that he reluctantly takes up the battle in order that goodness and justice may prevail – the heroic narrative, boiled down to its essence and infused into a local historic context for flavor and variety.

Sanshiro’s character clicked so effectively with wartime Japanese audiences that another helping was quickly ordered up to satisfy their appetite for his self-effacing bravery and unconquerable strength. Given the times and the waning fortunes of Japan’s army, Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two injects some fairly blatant anti-American propaganda into the mix. In fact, the first words heard as the story opens are in English, though it’s a barely comprehensible stream of verbiage that reminded me of the muttered grumblings that Bluto and Popeye directed at each other when fighting in the old Max Fleischer cartoons. An angry American sailor berates his hapless rickshaw driver for going too fast, and it seems like the kid misunderstands him as saying he’s not going fast enough. Of course the driver gets worn out quickly, tempers flare and the sailor gets assaultive. But just in the nick of time, a strong hand reaches out and grabs the cocked fist before it can strike again. It’s Sanshiro (the hero!) who was once a rickshaw driver himself and is now here to put a stop to this pointless cruelty.

The opening scene provides a textbook example of how to efficiently reconnect a sequel’s audience to the world and atmosphere they enjoyed so much the first time around. In the first film, Sanshiro was the driver who witnessed his eventual judo master fend off an unprovoked attack from a mob of jujitsu thugs by tossing them off a dock and into the water. Now its Sanshiro’s turn to echo that scene in Part Two’s initial action setpiece.

After comically dispatching the drunken oaf, Sanshiro is approached by the grateful rickshaw driver he saved from a beating. But the youngster’s praise prompts a troubling thought as it rekindles the vanity and brashness that Sanshiro has worked so hard to tame. The hero realizes that his struggles are not yet complete – he needs more tempering in order to properly harness his physical gifts. Again Kurosawa finds his way to reviving the underlying struggle that provided the first film’s dramatic tension, a dilemma that had apparently been resolved at the end of its story. We’re reminded that even the most venerable heroes and masters never fully arrive, but must continue to practice and strengthen their discipline in response to life’s ongoing challenge.

Sanshiro’s skirmish with the sailor draws the attention of an arrogant American boxer, William “Killer” Lister, who’s eager to test his fighting methods with the best that Japan can muster. (The war time applications for this device are so obvious that they hardly need to be spelled out here.) But the dojo rules prevent Sanshiro from fighting for entertainment purposes, and besides that, Sanshiro knows all too well the damage that playing to the crowd would have on his spiritual quest. The video clip embedded above is quite an anomaly, a Japanese film dubbed into Italian, without subtitles for the convenience of English-speaking audiences. Despite those obstacles, the sequence can easily be understood by any reasonably attentive movie watcher. Sanshiro observes the bloody brutality happening in the ring, sees one of his fellow martial artists step in to participate in the barbaric spectacle, and is moved to publicly object. He implores his countryman to change his mind and preserve his dignity, but upon learning who it is that addresses him, the jujitsu fighter informs him that Sanshiro himself is responsible for setting him on this path. As he turns around to see the appalling beatdown that follows, Sanshiro is forced to reckon even more deeply with his inner conflicts that seem so intent on manifesting in the external world. The scene effectively illustrates Kurosawa’s early grasp of cinema’s culturally transcendent, universal language.

Other super-hero conventions can trace their roots back to things that occur in Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two. As Sanshiro seeks the guidance of his dojo master and fellow judo disciples, his return is noted by an enthusiastic class of boys who refer to him as one the Four Kings of the Shudokan. That’s actually an angle that Kurosawa could have developed more, as the other so-called Kings never really get to show their stuff, the way they would in a hero film made nowadays like, oh, say, The Avengers, or something along those lines.

Still, without some kind of angst stirring up the plot, even the most charismatic of heroes become pretty dull characters in a hurry. Sanshiro’s remorse over the violence and defeat he’s inflicted upon others is just one variation of the temptation toward withdrawal and abandonment of the quest that the classic hero always has to work through. In voicing his indecision to the priest, Sanshiro lays his soul bare, and is sternly rebuked for it. “Fighting is a path to consolidation,” the priest intones. “You shall not feel peace through compromise or confusion.” In spurring on a fighting spirit and rejecting the seeds of doubt and equivocation before they can fully settle in, the priest’s sentiment also serves imperial propagandist purposes in addressing a war-weary populace. The priest’s admonishment to Sanshiro that “it’s not about judo defeating jujitsu, it’s about the survival of the Japanese martial arts,” translates naturally into Japan’s then-current fight for its very existence against the encroaching invasions of American sailors and soldiers.

Sanshiro’s noble quest receives a further shock and challenge when he’s confronted by the bitterly hateful brothers of Gennosuke Higaki, the karate master he defeated at the end of the first film. Tesshin, who succeeds him as both a top-rank fighter and Sanshiro’s mortal enemy, is actually played by the same actor who portrayed Gennosuke, though with a different hairstyle to avoid confusion, since both characters appear in Part Two. Presumably this is because actor Ryunosuke Tsukigata had all the moves down for the critical action scenes, and it provided some continuity for his performance and any fans he may have had. Still, it’s an interesting solution to the problem of who to cast as Sanshiro’s ultimate adversary. The younger brother, Genzaburo, leaves a strong impression as a man driven into mute insanity by the shame inflicted on his family due to their brother’s capitulation to Sanshiro on that grassy windswept hillside some years past.

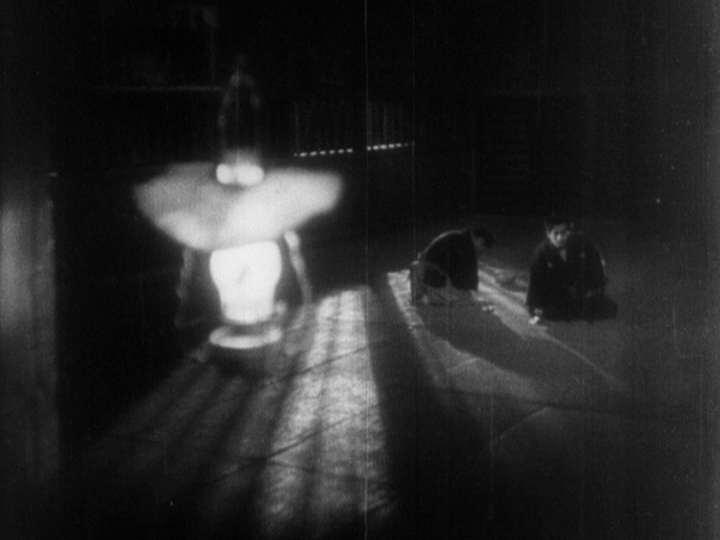

Before Sanshiro is ready to further his ascent toward the attainment of wisdom and inner tranquility, he first has to completely bottom out, again in keeping with the classic heroic narrative. In this case, his rebellion is expressed through overt disregard of the dojo rules against drinking on the premises. Late one night, when everyone else is sleeping, he’s too stirred up to rest. Instead, he grabs a sake jug and proceeds to get drunk right in the middle of the dojo floor. A friend intervenes, trying to talk some sense into him, and then another visitor enters, delivering a message, however indirectly, through actions more than words, that shakes Sanshiro to the core of his being. In his shame, the hero finds a glimmer of redemption, and his descent into self-destructive decadence is halted in time for him to resume his noble quest.

Still it remains unclear to Sanshiro what to do in response to the insults and provocations that the crazed brothers have directed at him, their open mockery of judo and their claim that it will always be inferior to karate. Moments after being advised by Gennosuke to simply avoid the taunts of Tesshin and Genzaburo, he hears a group of school children (in their inimitable squeaky voice choir) singing “stay away from Sanshiro,” and is reminded again of his fighting destiny. Yet he humbles himself to give a rickshaw ride to his former adversary, now a broken shell of a man who knows his end is near. Soon, Sanshiro’s righteous indignation is triggered and his resolve to see this conflict through to its inevitable conclusion is bolstered after a cowardly attack by Tesshin on one of the dojo students. All that, and a brief revisit to the first film’s love interest between Sanshiro and Miss Sayo create some fairly blatant, heavy-handed melodramatic touches throughout Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two, but they’re a necessary part of Kurosawa’s apprenticeship. Over the next decade, he would learn to convey similar feelings but with much greater depth and subtlety.

Sanshiro’s approach toward enlightenment begins and grows as he becomes more adept at balancing the seeming contradictions and ambivalence that surround him in his predicament. Renouncing his pride and pursuing anonymity, he becomes an even bigger celebrity. By showing mercy to an enemy who was intent on killing him, he provokes the hatred of two more who want to make him die. Desiring only peace, he’s still compelled to fight. And understanding the rules of the dojo, but knowing he willfully broke them, he expects to disciplined, so he resigns from the dojo in order to avoid being expelled in disgrace. But the priest thwarts his plan with straightforward permission: “The formalities are supposed to help you start down the path, but if the path requires, you must break those formalities,” and winds up his lesson with this Zen koan: “Concentrate on the man who’s bothering you… until he’s gone.”

Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two doesn’t fail to deliver in its promise of a dramatic, culminating face-off between the hero and his adversaries. First there’s the task of bringing Killer Lister to his knees, as the tall boxer finds his advantageous reach is of no helpful effect against Sanshiro’s precisely modulated force and leverage. It’s the same kind of pump your fist and cheer moment we all feel when a designated nationalistic champion puts a common enemy in his place. Though it suffers a bit from being filmed in difficult conditions from too far away (obviously before AK discovered the potentials of a telephoto lens,) the climactic showdown between Tesshin and Sanshiro echoes Sanshiro Sugata‘s finale in a rugged natural setting. Part Two’s battle takes place on a remote snow-covered mountain, in which both actors actually went barefoot for multiple takes in very deep drifts, all for the sake of authenticity. Those are some very tough dudes.

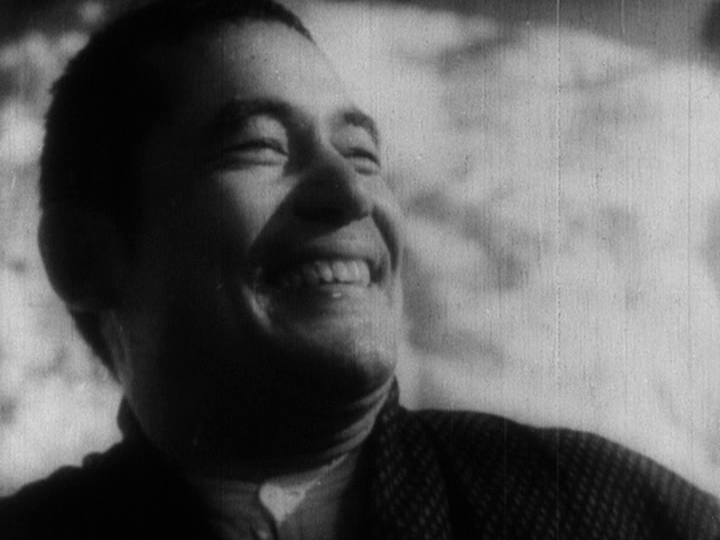

Following that last fight sequence, the story wraps up in a brief coda that offers poignant commentary on the times in which it was filmed. It’s hard to imagine a more devastating, catastrophic year in all of Japanese history than 1945, the year Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two was released. By May, when it opened, the biggest cities of the Japanese mainland were relentlessly subjected to American air raids.Three months later, a pair of atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As the DVD liner notes indicate, most of the theaters where the film would have shown were destroyed, and even those that still stood probably suffered from a dearth of customers. I mean, we all enjoy our movies but when buildings are exploding and people are dying all around, I think we’d have more important priorities than spending time in the theater. So no one can blame Kurosawa or the Japanese public for the fact that this sequel didn’t quite live up to expectations on the financial side of things. But that final exchange between the vanquished Higaki brothers, moving past their grudge and enjoying the bowl of stew prepared for them by Sanshiro, magnanimous in his victory, as they mumble “we lost” through smiles tinged with chastened relief and resignation, speaks volumes to the future that Kurosawa and the rest of Japan’s war survivors were about to face.