For the month of June, I’m trying something a little different for my (more or less) weekly review column here on CriterionCast.com. Going with the old tradition of June as the ideal month for weddings that I alluded to just about a year ago, in my second installment in this Journey through the Eclipse Series that covered Ernst Lubitsch’s Monte Carlo, I’m going to focus on the theme of Marriage. I’ve selected a few titles that concern themselves in various ways, and from the perspective of different cultures and times, with that venerable institution. That basic human phenomenon of coupling up and sealing the relationship with a set of vows is one that we can all relate to in some way, even if we haven’t taken that walk down the aisle (or in whatever other situation our culture and whims might lead us to arrange.) Marriage in its ideal form brings with it the promise of lasting happiness, joy and contentment, though we know that the reality is somewhat more complicated and occasionally disappointing than that, especially since these unions take place between actual people living in the real world. Let’s take a look at what some of the obscure treasures found in the Eclipse Series have to say about the pleasures and pains that accompany committed monogamous relationships. For starters, I’m going back to Lubitsch, the master of sly saucy comedy, and his final musical production, One Hour With You.

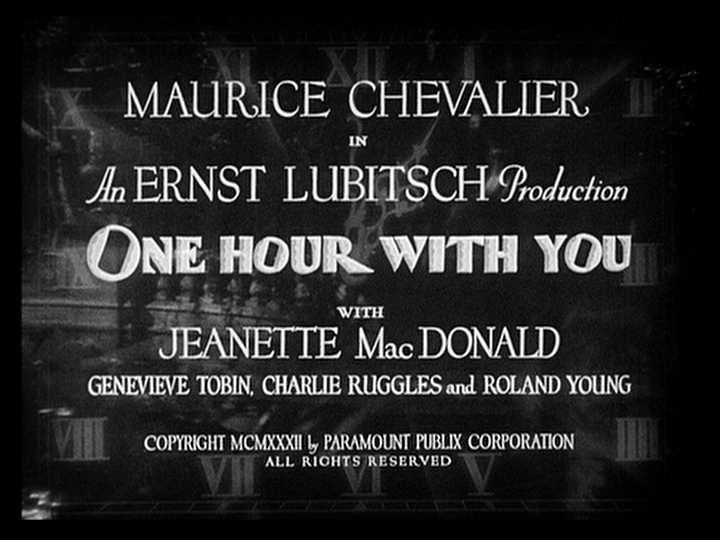

This film features a reunion of two great stars of the early musical-comedy era, Maurice Chevalier and Jeannette MacDonald, who each had their Hollywood breakthroughs in 1929’s The Love Parade, the earliest film in Lubitsch Musicals: Eclipse Series 8. They both proved so charismatic and popular with the public that they were each rushed into other productions as quickly as they could, but previous commitments prevented them from recreating their on-screen chemistry until One Hour With You was hastily thrown together in 1932, just as Lubitsch’s contract was winding up and he was en route to becoming one the titans of the Depression-era movie biz. The unusual credit of “directed by/assisted by” hints at a backlot tussle for control between Lubitsch, who originally only intended to produce the film, and George Cukor, then still an emerging talent who went on to a long and award-winning career. (He’s probably best remembered for directing The Philadelphia Story, the 1954 version of A Star Is Born and My Fair Lady.) Just a couple weeks into the production, Lubitsch took over the shoot, forcing Cukor to eventually sue in order to get his name back on the credit. Oddly enough, later that decade Cukor was also booted from his job as director of Gone With The Wind when David O. Selznick grew dissatisfied with the pace and quality of his work.

Like most of the great Lubitsch comedies (with Heaven Can Wait as a notable exception), One Hour With You is placed in a European setting, though it’s really more of a comic-fantasy version of Europe, populated by preening idle aristocrats and their servants, some of whom are hopelessly fastidious and uptight, the rest more or less content to let their libidos lead them freely, at least until they’re caught taking things a little too far, at which time, a hastily contrived alibi and touch of wit is employed to lower the tensions and ease their way out of trouble. No one epitomized that slippery, ingratiating charm more than Maurice Chevalier, perpetually beaming in on the ever-fluctuating opportunities for amorous encounters that seemed to come at him from all angles.

The film opens with a rhyming exhortation of the chief of police of Paris, lamenting the negative financial impact that too much “free” love-making in the local parks after nightfall has had on the local cafes and other establishments that rely on people spending money in order to find their next hook-up. It’s not the public displays of affection or the frisky romping around that draw the chief’s ire: it’s just that there’s not enough commerce involved in the transactions! So he sends his men out to break up the moonlight necking sessions that draw would-be lovers to Paris from all corners of the world, sending them to the hotels and restaurants where they’ll have to shell out some cash for their pleasures.

One of those sorties leads us to the Bertiers, Andre, a doctor, and Colette, the stars of our program, who contrary to all the build-up that’s taken place til that moment, really are a happily and respectably married couple, who just can’t seem to keep their hands off each other. Rich, attractive and endlessly delighted in their perfect match with each other – it’s just about enough to make you sick with jealousy, isn’t it?

After the cop shoos them back to the privacy of their stylishly appointed boudoir, Monsieur Bertier turns to the camera and directly addresses the audience for the first of several times in the course of the film, and it’s a pretty effective breaking of the fourth wall, especially for such an early stage in the development of sound cinema. For one, it makes his character, whose headed on a course of mildly resistant but ultimately weak-kneed infidelity, a lot more sympathetic, and funny, as we realize that despite his happy marital arrangement, deep down he’s still the same old scoundrel that we would have imagined he was – it’s just much more refreshing when he comes right out and admits it without us having to call him out on his hypocrisy.

And what makes his inevitable lapse all the more humorously ironic is that it’s his wife Collette’s best friend, the sex-crazed and relentlessly prowling Mitzi, who briefly but most definitely leads him astray. As luck would have it, one rainy afternoon Andre and Mitzi (still complete strangers to each other at the moment) wind up in the back of a Parisian cab, which given the mores of the time, their married status, and the presumption of perpetual arousal that all unaccompanied young spouses lived in, was practically grounds for divorce all by itself. Mitzi’s eye-rolling, innuendo-laced seductive verbal entanglements with Andre are simply delightful and hilarious, setting the stage for all the hijinks that follow.

Lubitsch and/or Cukor are also quite willing to toss in a few gratuitous flashes of skin and sight gags, all well within the bounds of propriety by today’s standards but so skillful in maintaining the mood of sophisticated, slightly naughty levity that pervades these Pre-Code films. It’s pretty sad to think of the shackles that were put on creative talents like Lubitsch and who knows how many others over the subsequent decades. Sure, the argument can be made that working within enforced limitations sometimes pushes artists to new levels of ingenious subterfuge, but I have a hard time avoiding the conclusion that a lot of very funny and insightful films aimed toward adult audiences never got made, or were pointlessly watered down for the sake of reinforcing ridiculous taboos.

And even though these old films are far from state-of-the-art in the visual and sound department, anyone who likes that vintage Art Deco look will find lots to relish in the set designs, wardrobes and stylish accents scattered generously throughout One Hour With You.

So let’s get to that marriage theme. As the stills above indicate, both Andre and Colette have to work through the zealous advances of their ardent pursuers. We’ve already touched on Mitzi, Colette’s pal who manages to go hard after her best friend’s man without ever tipping her hand to her supposed confidante. Mitzi is a certified home-wrecker, dissatisfied in her own marriage to an aging Swiss businessman who’s quickly realized he got in way over his head when he took that platinum floozy into his home, coming up short in every way when it comes to keeping her satisfied. But Collette has her hands full with Adolph, a close chum of Andre’s (he’s the guy in tights who was misinformed into thinking that the anniversary party that the Bertiers are throwing is a costumed affair.) Adolph’s passionate lust for Colette isn’t ever explained all that clearly (or maybe I was too busy laughing to take note when that particular bit of exposition rolled past) but the man is clearly smitten, and his earnest entreaties to sweep Colette off her feet will evoke chuckles and perhaps some wincing from guys who’ve had the misfortune to find themselves so pathetically exposed when pursuing a woman way beyond their reach.

But why rely on my description of these frisky roundabouts when I can just drop a short clip in here that will doubtlessly help you decide whether or not this kind of rom-com classic is right for you?

If there’s a lesson about marriage to be sifted out of all the nudging and winking inspired by an eighty-minute spin through One Hour With You, it’s that despite the disappointments that we may feel at the failures, inconsistencies and other all-too-human foibles of our dearest loved ones, we do ourselves the biggest favor by maintaining that readiness to forgive and remember what drew us together in the first place. Yes, Andre really does fall into temptation, and yes, he really ought to have known better than to meet his wife’s flirtatious friend for a midnight rendezvous while her husband was away (but with a private eye on duty.) Even with the overlay of randy comedy and Chevalier’s endless joie de vivre, Lubitsch is wise and realistic enough to stage a brief but important day of reckoning between the estranged couple, where he gets his face slapped and suddenly realizes just what he is in danger of losing – especially when his true sweetheart is just so damned cute!

Without getting all mopey about it though, just as important as forgiveness and grace is the ability to keep a sense of humor and a light touch when it comes to managing the affairs of our hearts. Sure, the swift and painless resolution that brings One Hour With You to its happy moment of closure, this time with Jeanette and Maurice both addressing their female and male counterparts in the audience, is a little too convenient and tidy to be fully believable, but Lubitsch is far from being any kind of a realist when it comes to his movies. A cynical view of the film might see it as an apologetic for cheating, minimizing the hurt that extramarital affairs definitely cause – and that view gains credence when it’s noted that Lubitsch chose this plot, a remake of an early German silent titled The Marriage Circle he shot in 1924, during the aftermath of his own divorce. Still, even acknowledging the reality that so often falls short of our ideals, One Hour With You, like all the other jauntily amoral Lubitsch musicals, beats with a joyful, life-affirming intelligence that understands just what it is, that endless pursuit of desire’s sweet fulfillment, that gets our heart beating and keeps our blood pumping.

Check out this new indie film:

http://xfinitytv.comcast.net/movies/Jelly/155899/1464430233/Jelly/videos