Last month, in the course of reviewing Hiroshi Shimizu’s The Masseurs and a Woman, I impulsively committed myself to review “next week” another 1930s Japanese film by Kenji Mizoguchi, in order to complete the sampler I’d started with recent articles on Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse from that same era. Of course, I followed up on that commitment seven days later with an article on The Rise of Catherine the Great, from the Alexander Korda’s Private Lives Eclipse set. And then last week I postponed my Journey through the Eclipse Series altogether, opting instead to write a column on Ten Criterion Films for Mothers Day.

So I didn’t really know which “next week” I was referring to, until now, when it’s finally time to make good on my promise. I guess it’s only fitting, after offering my thoughts on one of the most powerful women who ever lived (Russian empress Catherine the Great), and then turning my attention toward the many moods of motherhood last week, that I complete this informal survey of feminine role models by contemplating a prime example of the subject that helped make Mizoguchi famous: women beset by tragedy, scandal and social disgrace, at least in the eyes of a dominant patriarchal establishment. In fact, that archetype is so central to the director’s oeuvre that it’s embedded in the subtitle of this career-bookending box, Eclipse Series 13: Kenji Mizoguchi’s Fallen Women.

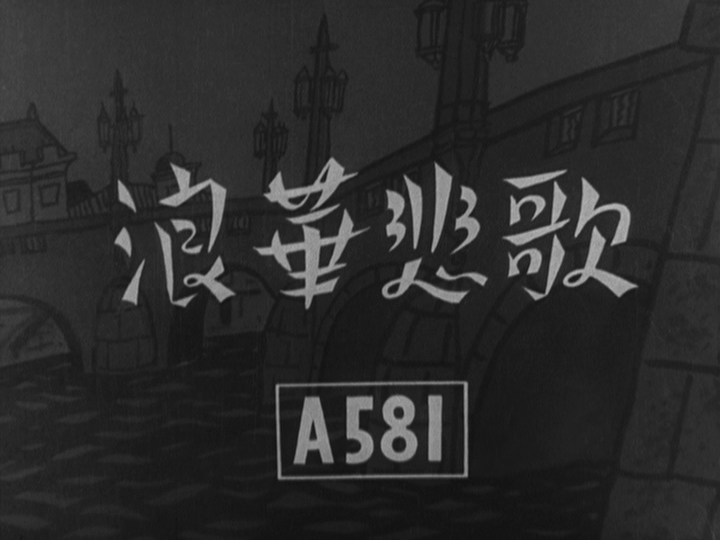

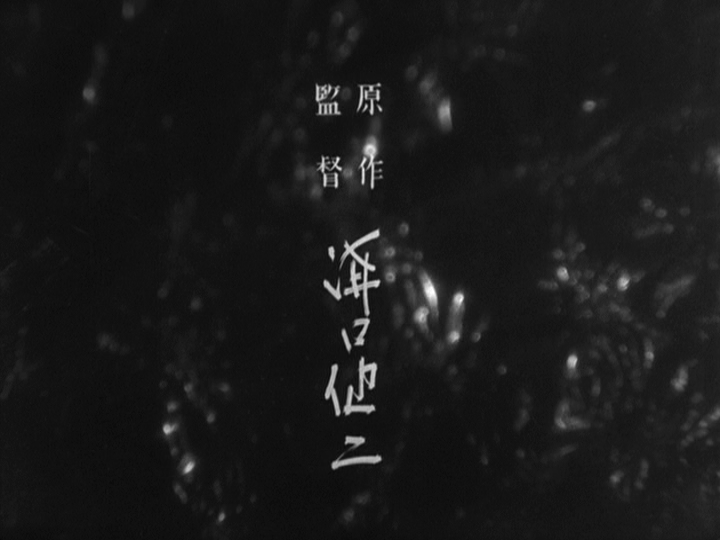

The film I’ve chosen is the one that authoritative sources, including Mizoguchi himself, cite as his breakthrough into artistic maturity, Osaka Elegy, from 1936. Having perfected his technical chops for over a decade cranking out dozens of short features in Japan’s silent film era, Mizoguchi found his voice in this story that depicts a modern, independent-minded woman’s struggle with the burdens imposed upon her by cruel and manipulative men. Among her exploiters are her own father and brother, oblivious to the sacrificial lengths she goes to in order to enable their security, as well as the corporate bosses who employ her, first as a switchboard operator, and later for their own carnal pleasures.

But rather than serving up Ayako’s downfall as a moralistic cautionary tale to warn young women about making the wrong choices at the formative stages of life, Mizoguchi has a larger point to make about the society he was a part of and the corruption at the top of the class hierarchy that created the wretched scenario of Osaka Elegy. And so he begins his story by focusing on a sad and rather repulsive couple, the Asais. Sonosuke Asai is the president of Asai Pharmaceutical Company, a prominent businessman in the industrial city of Osaka, who ascended to that highly respectable station in life by marrying his wife Sumiko, heiress to her family business and considerable wealth. That crass motivation is about the only thing that holds them together, as we quickly learn over the course of a painful breakfast encounter where they shamelessly quarrel and mock each other in front of their guest, Dr. Yoko. You can tell that Sonosuke is an evil corrupt man by the harsh light that flares off his lenses in the picture above, and the pained expression on Dr. Yoko’s face as his supposedly respectable hosts do their best to humiliate each other in his presences speaks eloquently as well.

The hostility that has saturated his miserable marriage pushes Sonosuke toward some kind of outlet to burn off resentment and reclaim some measure of self-respect. Unfortunately for Ayako, his path to that flimsy imitation of redemption crosses her own, as she finds herself in a vulnerable position not through any mistakes on her part, but because of her scoundrel of a father, who’s gotten in trouble for petty embezzlement that is beyond his capacity to repay when suspicious company officials come around, offering him a last chance to avoid public exposure of his crime. Instead of manning up and taking responsibility for his actions, he flatters himself with excuses and berates his daughter for confronting him (bluntly, for sure, but deservedly so) with the truth.

Sensing her vulnerability instinctively like the opportunistic vulture that he is, presuming a lack of virtue because of her unapologetic modernity, and clearly recognizing her beauty, Sonosuke summons up what little charm he can muster to make a move on Ayako, and backs it up with his undeniable advantage: money.

Though she bravely thwarts his proposition at first, Ayako’s own predicament suddenly gets worse when her father all but kicks her out of the house after an unvarnished exchange of words brings them both to the boiling point. Ayako has had enough. She leaves home, giving up her menial job, even disappearing for a short while from her young and genial boyfriend Nishimura, in order to take matters into her own hands. She accepts Sonosuke’s offer of an exchange: if she resigns herself to the boredom and debasement of being his kept woman, he’ll provide a discreet apartment and resolution of her father’s legal crisis. Ayako does this mainly for the sake of her younger sister who has no ability to care for herself, but also because she recognizes that there’s no one else capable of managing the problem any better.

As the plot grows more complex and Ayako becomes ever more entangled in the web of exploitation, Mizoguchi throws in other elements that add a touch of fascination to Osaka Elegy. Part of the “luxury” that Sonosuke offers to placate Ayako, perhaps to obscure the extent that she’s being used, is an evening’s outing to the theater, where she accompanies him in the attire of a respectable married woman. The night’s entertainment is a puppet show, featuring another squabbling couple, with a female manikin poignantly operated by a male puppeteer. Tipped off that her husband is out on the town with another woman, Sumiko arrives to create a scene aimed at shaming her husband, but once again a crafty man in charge steps up to improvise a false alibi on the spur of the moment, that at least buys Sonosuke a bit of time before his house of cards inevitably falls.

The whirlwind of deceit and hypocrisy continues to pick up speed, to the point where Ayako herself gets caught up in the maelstrom, resorting to her own devices of trickery in order to gain a measure of revenge and, if they’re willing to see it, reveal to the manipulative men around her just how depraved they’ve become. Turning the tables on Fujino, to whom she became a mistress after her arrangement with Sonosuke collapsed, Ayako thinks she’s achieved the upper hand in her dealings with men, especially now in her newfound confidence that Nishimura will take her as his wife.

But that sense of optimism is so very short-lived, as Ayako discovers that even the kind-hearted man she had confidence in is no match for the cynical determination of those in authority to crush any challenges to their rule. As Fujino brings in the law, supremely assured of its willingness to side with him against a lowly and easily vilified woman in this dispute, whatever feelings of love Nishimura once expressed for her quickly whither under the pressure of an investigator’s reprimands. The tough cop, played by a young and only distantly visible Takashi Shimura (years before he became a favorite lead actor of Akira Kurosawa’s), demonstrates the pitiless severity of a patriarchal status quo that doesn’t have to exert much effort in order to keep its citizens in line. Even those who, like Ayako, find it within themselves to rebel against injustice quickly find themselves isolated and without allies, however plain and morally defensible their cause might be.

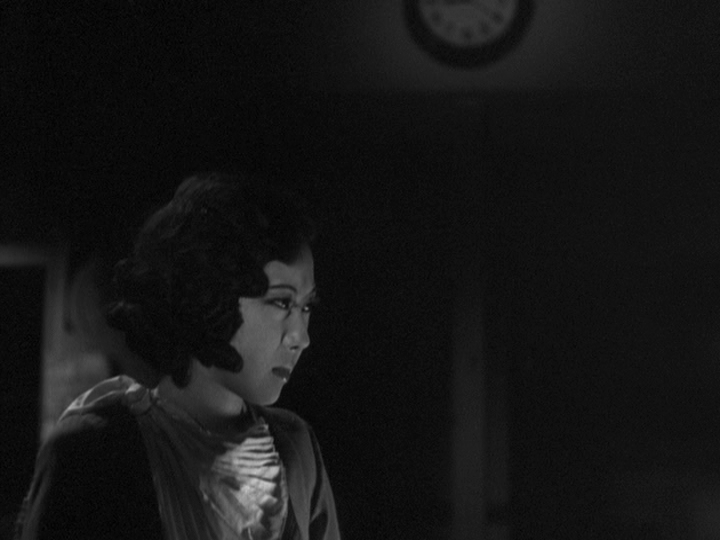

In addition to the conniving of her adversaries and the maddening series of desperate compromises to which she resorts in order to rescue her ungrateful family, Mizoguchi pulls us into Ayako’s dilemma through forebodingly bleak visual compositions. This is indeed one of the darkest films I’ve seen in a long time – not merely thematically in its portrayal of social relationships, but also in the utter absence of light. Huge swaths of opaque blackness crowd in around the perimeters of most scenes, with most shots framed at a distance and only a few strategically placed close-ups to bring us near to the perspective of our protagonist. This video clip, an interesting fan edit of “the second film hidden between the moments,” offers a good sampling of Mizoguchi’s technique, sans actors. Some of the charcoal haze through which we view Osaka Elegy is undoubtedly attributable to the effects of time and minimal efforts at film restoration. While a more pristine print would be nice to have at our disposal, this is an instance where one could argue that erosion enhances the atmosphere Mizoguchi intended to create.

Those who’ve seen Osaka Elegy are most likely to think, when first prompted, of its final scene, with Ayako now cast aside and rejected by her family and the men who once flattered themselves through their purchase of her services. Mizoguchi’s coup in bringing this briefly told tragedy to its close is to not take what would have been the obvious route, showing Ayako finally broken, tearful, perhaps penitent but in any case pitiful. It would be a natural tendency for any director; one could not fault him too much for choosing to give the audience what it both expects and enjoys.

Instead, Mizoguchi has Ayako striding purposefully, not so much with confidence as with sheer determination, into a future certainly fraught with risk and with little promise of reward or lasting vindication. But Ayako will face it on her terms – her abrupt turn and straight-on gaze into the camera at the end has a 23-year jump on Antoine Doinel’s similar move at the conclusion of The 400 Blows. (Maybe if Mizoguchi had gone with the freeze frame here he’d get more credit? I dunno.) Audiences of the time probably had little sense of how impressively Mizoguchi would build upon this final flourish, or the magnitude of achievements yet to come. For those like me who mainly know him for his later award-winning masterpieces like Ugetsu or Sansho the Bailiff, Osaka Elegy is an essential re-introduction to a phenomenal cinematic artist.

A few other bits of information I forgot to include: last Monday (May 16) was Kenji Mizoguchi’s birthday, and May 28 is the 75th anniversary of Osaka Elegy’s original release, if you’re looking for a special occasion reason to watch this film. It was also recently added to the ever-growing lineup over at Hulu Plus!

So I think you’re saying there’s no excuse now to not check out this amazing film? :)