I’m getting near to the end of my first complete cycle of reviews from the 24 box sets released (so far) in Criterion’s Eclipse Series, and as any regular reader of this column knows, I usually try to tie my review to some current event or holiday occasion. We’re in the countdown to Halloween, but as I scan through my collection, I don’t really see anything fitting into the horror genre featured in our October podcasts and many other movie-related websites this time of year.

That leads me to suggest that Criterion consider putting together an Eclipse entry of obscure scary movies in time for my columns next fall! But in the meantime, I really have to stretch the connection here, drawing an admittedly weak link between the seasonal pastime of pumpkin carving and this week’s selection, Rusty Knife, from Eclipse Series 17: Nikkatsu Noir.

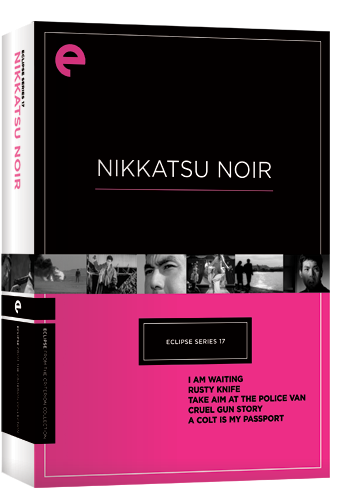

Nikkatsu Noir is unique among the Eclipse Series in that it’s not focused on the works of a particular person but on representative samples of a studio’s crime genre output over a ten year period. Released in 1958, Rusty Knife is one of the earlier selections in the set, and the first of its titles I’ve seen. The liner notes indicate that the film was a big hit at the Japanese box office and it’s not hard to understand why, pairing a couple of popular young actors, Yujiro Ishihara and Mie Kitahara, who had helped kick off a cinematic youth uprising of sorts two years earlier in Crazed Fruit, where they played scandalously sexy but ill-fated teenage lovers. (I recommend seeing that film in close proximity to this one if possible, in order to better appreciate their chemistry and how their on-screen personalities evolved in the early stages of their respective careers.)

Their star power only enhanced the appeal of this fast-paced gangster story set in Udaka, a new city established in the flourish of Japan’s postwar industrial development. The combination of slapped together civic authority and sudden economic prosperity proved irresistible to organized criminal enterprises and difficult for law enforcement to manage when the crooks started feeling a sense of entitlement to the fruits of their corruption. A whole generation of Japanese youth were coming of age, many of them survivors themselves of the kinds of temptations and moral conflicts that drive the dilemma of Rusty Knife‘s protagonist Tachibana, a young thug trying to go straight.

Tachibana’s problem stems back half a decade, when he and a couple of his pals looked to pull off a routine burglary for cash in the office of a local politician, but chanced upon a murder-in-progress designed to look like a suicide instead. After they’re discovered as witnesses, crime boss Katsumata pays them off to ensure their silence, a bribe that’s maintained its effectiveness ever since. This despite Tachibana’s eventual five-year incarceration for murdering the rapist of his girlfriend, a trauma that led to her subsequent suicide.

Recently sprung from prison after serving his time, Tachibana now ekes out a living running a hole-in-the-wall bar in downtown Udaka. He keeps his impulsive sidekick Terada, one of his fellow witnesses to the murder, close at hand by employing him at the bar, but the third member of their crew, Shimabara, shipped off to Tokyo years ago and they’ve since lost touch.

Now the authorities have decided it’s time to move in and crack down on Katsumata’s gang. They arrest the kingpin with the sinister chuckle and put out a desperate call for witnesses, anyone with dirt on the guy who’s willing to talk about it. An anonymous letter arrives at police headquarters, detailing the murder that Tachibana and his accomplices stumbled upon and ramping up pressure from the cops for them to testify about it in court. Word of a potential stool pigeon leaks out to Katsumata and his cronies, and they resort to the usual methods of ensuring that incriminating evidence never makes it into court.

Pinned down by intimidation from the big boss, the pangs of his conscience, and anxiety that his friend Terada’s recklessness in handling his affairs will only lead to trouble, Tachibana veers ever closer to the snapping point that just might force him to pull out that Rusty Knife, the killing tool that’s lain dormant for so long but lurks just below the surface of his increasingly strained self-control.

So the last thing Tachibana needs as he struggles to contain the beast within is a romantic interest who enters his life with new information about the events behind his late girlfriend’s abuse, and the fake suicide he witnessed that led to so much adversity. But that’s exactly what he’s forced to deal with in the figure of Keiko, a pretty documentary filmmaker who happens to be the daughter of the murdered politician.

Keiko has her own obstacles to navigate as she seeks to discover the truth behind the stories she’s heard about her father’s death and the multiple layers of fraud and deceit that surround the supposedly honorable inner workings of Udaka’s political culture. She senses that Tachibana knows more than he’s willing to let on, and urges him to speak up for the sake of the city’s crime victims, if not to simply relieve his own torments. The various conflicts at play throughout Rusty Knife tap into tensions that gripped Japanese society along generational and economic fault lines at this time.

Few are likely to list films like Rusty Knife or the other Nikkatsu Noir offerings among their list of all-time greats, even among Japanese films of the era. A decade earlier, Akira Kurosawa visited similar themes of underworld corruption and the relative impotence of local governments in films like Drunken Angel and Stray Dog, and I think his explorations resonate more deeply and warrant closer scrutiny, partially because of their place in his remarkable oeuvre and partially because they were created at a more pivotal turning point in contemporary Japanese history, in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Where Rusty Knife and its companions in this box set outperform the early Kurosawa films is in their growing mastery of coolness, from the swanky theme song and a deliriously swervy downtown motorcycle ride to a hard-charging high-speed dueling truck drag race and other elements of that jazzy neon vibe, begun in the late 50s and destined to pick up steam in the decade to come as the Japanese take on film noir grew ever more confident and distinctive in its own power and vocabulary. Fans of gripping double-crosser plot twists and testosterone fueled tough-guy showdowns ought to find Rusty Knife plenty sharp enough to leave a lasting impression.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

I almost picked this one up at the last 50% off sale at B&N. Glad you gave comparisons to Kurosawa’s early crime dramas as this looks like something in the same ball park. I particularly liked Stray Dog and from watching the trailer for Rusty Knife I’m putting this set back my to own list.

That’s a good pick, Kyle. I’d rank Nikkatsu Noir near the top of the Eclipse Series for sheer entertainment value. These films are fun to watch, not overly complicated but still pretty fascinating. I plan to return to this series quickly after I’ve completed my first go-round through all the different sets!