Just a few days before the end of 2010, a great Japanese actress passed away. Hideko Takamine had spent the majority of her lifetime in the movie business, debuting in 1929 as a child star that some called the ‘Japanese Shirley Temple’ when she was only five years old, and continuing to perform on screen for the next 50 years.

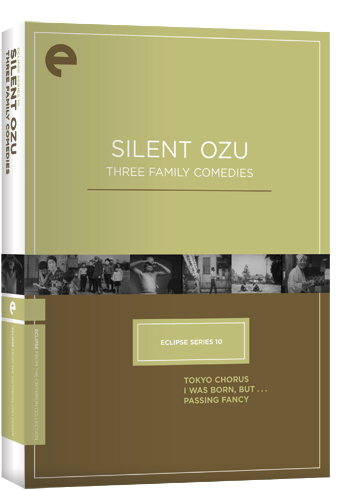

Particularly famous for her roles in the films of Mikio Naruse, her passing drew a flurry of responses a couple weeks ago, quite appropriate given the magnitude of her accomplishments, even if she’s not exactly a household name to most American movie fans these days. For this week’s Journey through the Eclipse Series, I’m taking the opportunity to showcase one of her earliest appearances on film, Tokyo Chorus, from Eclipse Series 10: Silent Ozu.

As it turns out, Takamine’s role here doesn’t amount to a whole lot, certainly nothing that would approach or significantly add to the lustre of her accomplishments in the Naruse films or in her triumphant performance in the 1954 classic Twenty-Four Eyes, in which she plays a beloved school teacher whose courageous stand in the face of pre-WWII paranoia and oppression prompted an emotional catharsis for Japanese viewers at the time.

That role, and a number of others, established her place in the highest pantheon of female Japanese film stars. As for what she achieved in Tokyo Chorus, I’ll give her credit for a measure of cuteness and charisma, but to be perfectly candid, her role here is pretty basic; any number of child actors could have pulled off what was asked of her. Still, the fact that the same little girl we see in this film went on to have such a celebrated career is significant in and of itself. I have to conclude that her early involvement in cinema played an important part in preparing her for future glories.

As for the film itself, Tokyo Chorus marks the emergence of Yasujiro Ozu as a major director, where his classic form and style first come to full fruition, in the service of a low-key family oriented story that helped orient the director’s future efforts in that vein. Though released a few years after sound had been introduced into the movies, Tokyo Chorus is a silent film, Ozu’s preferred mode up until 1936, when it became commercially unfeasible to avoid the use of spoken dialog.

In addition to this, today’s viewers are further challenged by the fact that Tokyo Chorus comes to us in very rough shape. The film is so worn and tattered that I can’t help but wonder if we are watching a transfer of the one and only existing print. Though the blotches, scratches and scars are severe enough to distract us from the story at hand from time to time, they also lend an air of solemnity and reverence to the experience of watching this venerable relic of a bygone era.

Ozu starts off his film with a prologue of sorts, showing his protagonist Shinji Okajima as a high schooler several years prior to the film’s main action. It’s a brief vignette intended to show his characteristic traits as a likable slacker and goof-off, tendencies that follow him into adulthood and his career path as a salaried employee in a Tokyo insurance agency.

The comical scene ends with an early example of Ozu’s trademark ‘pillow shots’ that employ relatively static images of nature and civilization in a degree of tension to serve as transitions from one scene to the next.

When we next meet Shinji, he’s married, with three children and burdened with the anonymous drudgery that is the fate of struggling workers still stuck on the lower rungs of the career ladder. He’s doing his best to be a good husband, a decent dad and adequate bread winner.

But the arbitrary and unjust principles that govern the business world rankle him, and in a fit of impulsiveness, he decides to stick up for a co-worker who’s been treated unfairly. This results in his firing, and of course he has a bit of difficult explaining to do when he gets back home to a disappointed wife and family.

On top of all that, his daughter Miyoko (yes, performed by Hideko Takamine) falls ill, requiring expensive medical treatment and hospitalization.

The crisis presses the young family to its financial breaking point, and a reminder is in order that this film was made in 1931, as the Great Depression was impacting economies all around the globe.

The above clip, in which Ozu brilliantly captures the subtle dynamics of a husband and wife in conflict who nevertheless have to work it out quietly and stoically for the sake of the children and domestic tranquility, provides a striking example of just how assured his film making technique had become even at this relatively early point in his career.

Yes, the image resolution is low, and it may not seem quite as poignant to the first-time viewer outside the context of the full film, but I think anyone who’s come to appreciate Ozu’s emotional and technical prowess will understand just how effectively he composed that section of the film.

Beyond the family-oriented exchanges that anyone who’s had to raise children on a limited income can easily relate to, Tokyo Chorus offers a variety of other pleasures, including some nice vintage exteriors from the old city of Tokyo, before it had been transformed even further into the gleaming neon metropolis we’ve known for the past several decades. And it’s also easy to admire Ozu’s social conscience and earnest desire to boost the morale of Depression-era Japan.

No doubt, Shinji’s plight, to provide for a family and prop up his own self-esteem even as discouragement and futility loomed large in the circumstances surrounding him, resonated with quite a few men who watched this film in its original context, and let’s face it, things aren’t a whole lot better for many of us these days as our own economy struggles, jobs are hard to come by and people capable of a lot more than what the job market offers have to settle for whatever is available at a given moment.

Even though Tokyo Chorus bears all the marks of an antiquated old artifact of a film, there’s still a potent and relevant message about personal reslilience and determination through adversity that we can glean from it today.

I just watched that video clip again and want to assure anyone interested in this film that the DVD looks a LOT better than what you get thru YouTube! The film has a lot of blotches and scratches, but the underlying image quality and contrasts are much clearer than this brief sample might lead you to think.

I think that Takamine’s role should not necessarily be overshadowed by, as you state, “any number of child actors could have pulled off what was asked of her”. Back then, children typically played very morose roles, clinging to their suffering mothers as a trope that dates back to kabuki. That Takamine was a vibrant, active child a la Shirley Temple, The Little Rascals, etc. was something new for Japan and one of the things that set her apart from other child actors at the time.

I appreciate you putting in a good word for Hideko! Sounds like you’re more well-versed in the conventions of Japanese film from that era so I’m definitely open to your insights. My main point I guess is that her role is fairly small in this film, though she does a fine job in it – definitely conveys a bright and energetic personality. It’s probably hard for me and other modern viewers to adequately understand what made her unique among her peers, especially as we’ve gotten so accustomed to generations of kid actors who’ve been taught the ins and outs of showbiz almost from infancy.

Yeah, that’s understandable. I would certainly see things that way, too. Takamine is my all-time favorite actresses and I’m actually writing a tribute to her which will also include a bio of sorts with her numerous contributions to film.