Last night, at the end of a busy week at work when I was just in the mood to hang out at home and unwind a little, I decided that it was a good time for me to wrap up my viewing of Criterion ’68 by ingesting an assortment of short films that had accumulated, like the last crumbs of cereal at the bottom of the bag, in my chronological checklist of films that I’ve been blogging about over the years. It was a suitable occasion for me to fully immerse myself into what turned out to be a festival of random weirdness. My wife, recovering from a bout with illness, was feeling a bit better but wanted to find a productive use of her time with the resurgence of energy, so she kept herself busy by working on a new quilting project. That left me free to indulge without guilt in the companionship of my trusty Blu-ray player as I turned my attention to a bizarre little variety show of avant garde eccentricity that I’ll elaborate on in the comments below. Each of the films I watched will receive its own capsule review, of whatever length and breadth seems appropriate as I let the words spill out of me forthwith.

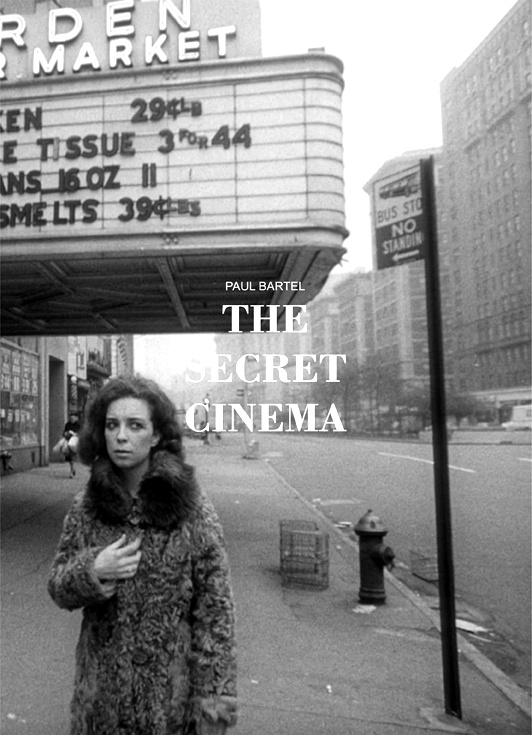

The Secret Cinema (directed by Paul Bartel)

The evening started with the most conventional narrative driven film of the bunch, a half-hour sketch that marked the debut effort of the guy who went on to direct Eating Raoul. My research shows that it was filmed in 1966 and the trained eye can see that from the fashions and general demeanor of the characters in the story. Their look was still a bit more prim and mod than shaggy, indicating that the full blown hippie era had not yet launched. It’s definitely an example of the “bad acid trip” movies of its era, focusing on the psychic breakdown and paranoid anxiety afflicting a vulnerable young woman as she is forced by circumstances to question the reality she lives in and its apparently malevolent intentions toward her. In this case, the effect is more comedic, at least on the surface. The story involves Jane, an office worker that we first meet in a scene where she’s being ogled and hit on by her repulsive fat slob of a boss. The scene is incongruously accompanied by a laugh track – at least, it feels out of place in the moment as the viewer isn’t aware that this is a vintage 1960s TV show. Nor is the scene actually all that funny. I don’t even think that audiences of that time would have found it all that amusing despite the greater tolerance in that era of sexual harassment in the workplace. But we do get the sense that others besides ourselves are watching, and that’s a strange feeling. The strangeness continues as we watch Jane move through a series of encounters with other characters, whose words and actions continue to agitate her – there’s a break-up scene with her boyfriend Dick, who doesn’t like girls but only cares about the cinema. Jane’s response is to go home and vandalize her own apartment, tearing movie posters down from the walls. She shredded nice-looking prints from Gone With the Wind, Louis Malle’s The Lovers and a seemingly forgotten Jean Seberg follow-up to Breathless once known as Playtime (before Jacques Tati claimed that title for his own purposes) but now referred to by its original French title, La récréation. What a shame to see them go to waste! But apparently her fury led her to at least temporarily renounce the cinephilia she had adopted as her own, presumably in an effort to secure her boyfriend’s affections.

From there, she continues her interactions with a variety of people whose words and non-verbal expressions cumulatively build the impression that there’s more going on here than meets the eye, something vaguely sinister and conspiratorial, where everyone except the woman at the center of the story is in on a secret that persistently eludes her detection… until its too late. The conceit is that Jane’s life is being filmed as she goes through the motions of each day, and those closest to her are the very same folks who are steering her from one hilariously frustrating situation to the next, just for the sake of their own twisted kicks and their dedication to the so-called “art” that they think is derived from the cinematic portrayal of her bewilderment and suffering. The story winds up with Jane sitting in the lobby of a “secret cinema,” locked out of the theater itself, where all the people important to her are sitting in the audience, laughing derisively at her misfortunes as she can hear (and mentally recall) her own responses to the things said to her by those very same friends and family members. What a dissociative nightmare! The film is a fairly amusing and clever realization of the common notion, “what if my life was a staged production, manipulated by people who only act as though they like me and consider me their friend?” It’s obvious that Bartel had a lot more imagination than budget to work with, but I thought he pulled it off pretty well under the circumstances. Overall the tone got things off to a good start by invoking a palpable sense of meta-self-awareness as I proceeded further down the path into genuinely deep audio-visual obscurity.

Diatoms (directed by Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon)

The clip above starts off pretty much like a standard Jean Painlevé “science is fiction” film, with a witty but factually sound summary of the then-current knowledge of whatever natural phenomena were up for discussion (even though its in French, and this fragment isn’t subtitled.) Particular attention is paid to the mystery of how the diatom, a single celled organism classified as an algae that is a basic building block of life on earth, is able to propel itself through liquids, since they don’t appear to have any fins or limbs or other visible means to gain traction. But as tantalizing as that mystery is, its merely an entry point into an utterly bizarre and alien realm that is simultaneously mind-blowing to consider and also common as dirt. Scientific considerations are given due attention for roughly the first half of the film, but there comes that point where the visuals and the music just take over and we’re left to contemplate visuals of almost hallucinogenic intensity. This film, just as it is, without any edits, would have been a perfect interlude between sets by the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead at the old Fillmore Ballroom back in 1968.

Saute ma ville (directed by Chantal Akerman)

This supplement from the soon-to-be-upgraded Jeanne Dielman DVD was Akerman’s first film, created when she was a precocious and rather adorable 18 year old. The title translates to Blow Up My Town. As she herself said years later in the video intro she recorded for this release, it contains all the elements of her later masterpiece, being filmed almost entirely in a kitchen and focusing on various domestic tasks involving food preparation and household maintenance. Except in this case, the frenetic, distractable, hyper-active Chantal (who is the only person we see on screen) is just the opposite of Jeanne’s famously methodical self-imposed discipline. Maybe its the contrast between reckless indulgent youth and a more temperate middle age, or the difference between being a person without financial responsibilities or even a strong desire to go on living and someone who feels compelled to carry on with the grind despite the lack of any tangible relief from the struggle in sight, simply because one’s duty must be served. Viewers are left to read whatever meaning they can find in Chantal’s playful orgy of consumerist destruction and self-indulgence. Personally I find the whole thing quite cute. It induces a lot of smiles from me to see her having so much fun. That wasn’t always the case in so many of her later movies, so it’s nice to see her cutting loose to get things started in her artistic career.

Maxwell’s Demon / Surface Tension (directed by Hollis Frampton)

Maxwell’s Demon is Hollis Frampton‘s famous trend-setting workout video of the late 1960s. Commit to doing the routine three minutes each morning, and in just a few weeks you too will be violating the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Be the first on your block! Impress the girls and show those bullies who’s the boss.

Surface Tension tests the viewer’s patience with nearly four minutes of an old fashioned landline telephone ringing over and over again, while a nameless young man wearing a natty vest and scarf ensemble mouths a wordless monologue at the audience as he fiddles with an archaic digital clock. Yes, tension is definitely produced here. It’s broken up a bit near the mid-point of the film as the camera embarks us on a sped-up stroll across the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan where we shuttle past a variety of landmarks and street corners (“did we just pass Paul’s Boutique?”) that I know are more familiar to millions of watchers than they are to me, accompanied by a German-speaking tour guide whose comments may or may not have anything to do with what we see on screen. The journey winds up in Central Park and I was half-expecting that we’d land as an observer of William Greaves as he was filming Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One. Unfortunately, the timing wasn’t quite that perfect. A grating buzzer silences the German, and a goldfish shows up at the end to silently explain it all. I think this is as good an entry point as any for the general viewer to decide how long they care to join Hollis Frampton on his cinematic odyssey.

The Alphabet (directed by David Lynch)

I’m not going to press myself too hard to try and figure out what this portrayal of a childhood nightmare actually intends to communicate in terms of meaning or real-life application, so sorry to disappoint anyone looking to me for such clarification. For such a short and ultimately trivial film, David Lynch certainly impresses me with the technical execution of his concepts and the lingering staying-power of his relentlessly warped and disturbing imagery (sonic as well as visual.) As was the case with Six Men Getting Sick, I was struck by just how ahead of its time this film feels. Not that I have any problem at all with how the cinema of the 1960s “feels” – indeed, I love that era and I’ll be sad to leave it behind whenever I get to that point in my blogging journey. But more than anything else I watched last night, this gruesome psychotic meltdown seems like an artifact that invades our consciousness from outside of time. The primal agony of that poor girl, stuck in her bed while her mind carries her off on a terrifying exploration of the abyss that learning and conceptual thinking opens up before us, summons up memories from a much earlier time of life, before I was aware of calendars and clocks and books and letters. Little did I suspect at the time what kind of complications all that would lead to. So far at least I haven’t had to experience uncontrollable gushings of blood, but Lynch seems to be telling us that it will happen soon enough in any case.

The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins / Mr. Charlie Your Runnin’ Mill is Burnin’ Down / The Sun’s Gonna Shine / Lightnin’ Les / God Respects Us When We Work but Loves Us When We Dance

I’m thankful that this handful of early Les Blank films was lined up in the queue to rescue me from the perilous perch of quivering ghastly astonishment that my evening’s bill of fare had led me to up to that point. Ain’t nothin’ like the bracing world-weary truthfulness spoken by a wizened old country blues picker to bring me back down off the ledge and spare me the inconvenience of accepting David Lynch’s persuasive invitation to rapid self-immolation. I’m not going to post any clips from these films here, even though there are plenty available to view online, simply because they deserve, really even demand to be seen in the best sound and image quality available. They really are that beautiful, and calming, and hypnotically pastoral in their own way, a genuine balm to my soul.

The first four of the films named above are all cut from the same cloth, consisting of footage that Les Blank shot in 1967 down in Texas when he paid a visit to the home of blues singer and guitarist Sam “Lightnin'” Hopkins. Hopkins was a famous, practically legendary figure in the contemporary blues scene, with a pedigree that reached all the way back to his childhood when he was played alongside Blind Lemon Jefferson, one of the seminal artists of that style of music. But viewers who come to this film not knowing much about Hopkins or the blues in general can be forgiven if they draw the conclusion that Blank was just toodling around with his camera and sound recorder one day when he just happened to stumble upon this incredibly charismatic down-home figure from whom the most exquisitely melancholic musical wisdom just flowed. Hopkins definitely had a persona and his delivery is just as perfect for the camera as it must have been for live audiences. The experience of a lifetime, playing in juke joints and fancy night clubs, on street corners and front porches, is all distilled into his riffs of pithy wisdom and hard-earned insight on how life goes, and how the blues feel when they churn a man up on the insides and demand to be released for the rest of the world to know what he’s been through. Les Blank enfolds Hopkins’ lyrical utterances in a rich, beautiful tapestry of local culture, flowers in the sunshine and the rustic landmarks of deep south country village life, seamlessly editing his footage together with an eloquent poise that respectfully mirrors the delivery of the film’s central figure. The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins is an apocryphal gospel tract, one could say, the main event here, with the other short films basically consisting of verses snipped from the final edit of the scripture.

And then there’s the grand finale, as far as the evening’s program was concerned anyway. God Respects Us When We Work but Loves Us When We Dance is the cumbersome title given to a document to the great Los Angeles Love-In of 1967. That event took place on Easter Sunday that year, as we’re informed in the opening credits, and what we experience from that point is what I would call a transcendental pilgrimage back to the prenatal stage of what would soon be called the Summer of Love. Other than the differences in locations, much of this footage could have easily been blended into D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop without anyone noticing.

A large crowd is gathered on the lawn of a public park. Bands perform on a stage set up for the occasion, but they’re not the only source of music, as more spontaneous groups of instrumentalists are seen at various places in the crowd – the sounds of drums, flutes, tambourines and more fill the air, and bodies sway and whirl, shake and tremble in response. The sun is out, the colors are bright, a cross-section of hippiefied humanity assembles on the green in order to take in all manner of stimulations and express their response, individually and collectively. Fortunately for the rest of us, Les Blank was tipped off in time to get his equipment and crew together so that he could capture a fragment of the wild energy unleashed that day for us to gawk and marvel at. Once again, Blank does an incredible job assembling and sequencing the clips into a cohesive and poetic whole. The confident gestures of a beautiful young woman with dark hair and elegant poise serves as a framework at the beginning and the end of the film, as the mood starts off brightly festive, eager and anticipatory, builds in intensity as the physical exertions become more strenuous in response to the quickening pulse of the music, and then launches up to reach a euphoric peak that plateaus into a realm of ecstatic contemplative realization, before making its gradual descent into a pleasantly fatigued appreciation of each others presence and companionship along the way. We see once again that lovely dark haired woman, waving her arms, swishing her skirt, holding her bouquet of wildflowers aloft in the late afternoon sunlight, and suddenly that long rambling title that Les Blank attached to this glimmering composition of sound and light makes all kinds of sense.

Previous: Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One

Next: Mr. Freedom