David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

This subdued hour long late-career enigma from Orson Welles initially feels a bit sad and anti-climactic when it’s presented as his “final completed fictional feature” (as stated on the back of the new Criterion Collection release.) A quiet, languidly paced adaptation of an Isak Dinesen short story, there’s very little action to stimulate the senses much of the time, with most lines delivered by actors sitting down, standing still and speaking rather quietly. When the tension ramps up a bit toward the end, the self-conscious art house touches run a great risk of falling flat and coming across as unintentionally comical. But the excellent 4K restoration, a well-curated selection of supplemental features, and above all else, the compelling presentation of a great man and cultural innovator entering his artistic decline makes the new Blu-ray package of The Immortal Story a practically essential addition to the home media collection of anyone who’s been enchanted by the protean genius of Orson Welles.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

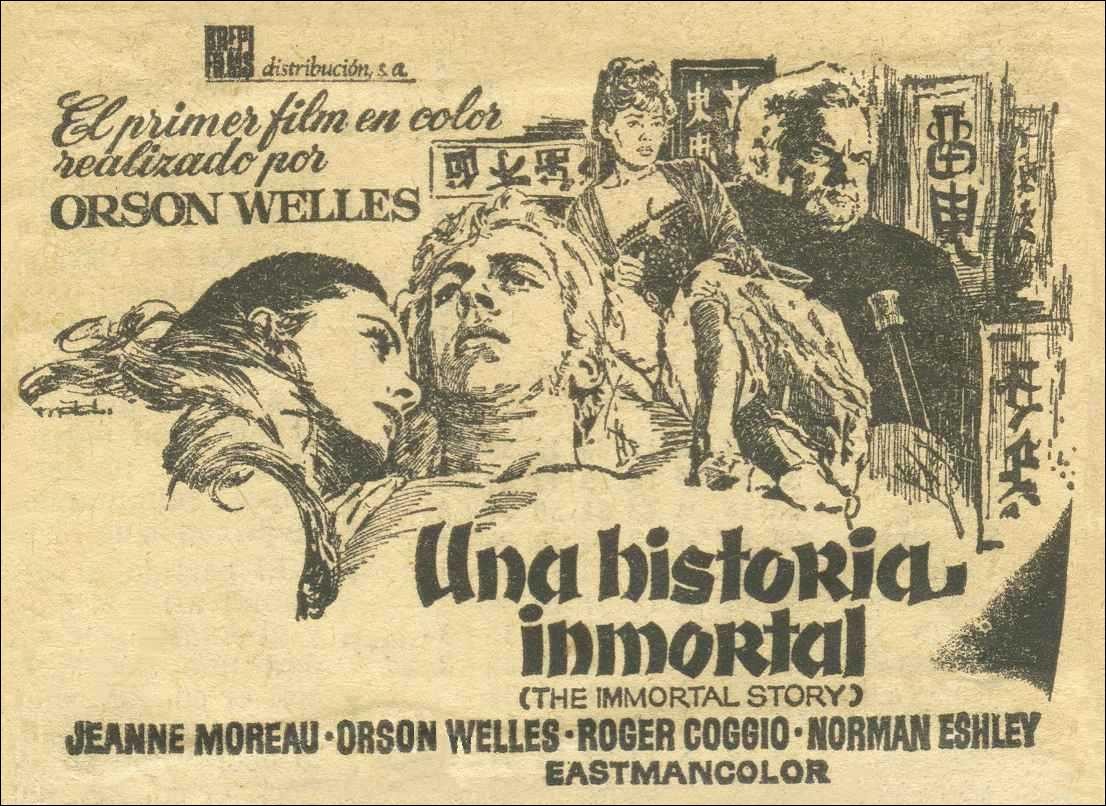

The original intention of The Immortal Story was to pair it up with another Dinesen adaptation of similar length, resulting in an anthology film based on the work of Welles’s second favorite author (besides William Shakespeare.) That other part was never made due to production difficulties Welles encountered in Budapest, so we can at least be thankful that this one was finished, even though a few rough patches and expedient compromises are apparent. Filmed mostly in small villages located in Spain, Welles uses his sleight-of-hand magic to convince us that we’re watching scenes set in the former Portuguese colony of Macao (just across the Pearl River Delta from Hong Kong.) Actually, it’s not really all that convincing, but just go along with him, it works better that way.

The story involves Charles Clay, a grizzled, extraordinarily wealthy but lonely and embittered old man, played by Welles himself, of course, who possesses but one last unrealized ambition: to witness the fulfillment of a captivating sailor’s tale that he once heard while passing the time as a passenger on a ship. Terminally bored by the contemplation of his business concerns, impatiently contemptuous of the yet-to-be-fulfilled promises of biblical prophecy, Clay recognizes his own impotence as the collapse of his physical and emotional strength becomes ever more impossible to deny. All that’s left to him is the power that his money and his strength of will can exert. So he summons his waning resources and applies them to the creation of a scenario presented to him in the story of a young shipmate who’s hired for a generous price to enter an heirless rich man’s house and impregnate his young, beautiful wife.

Since Clay is unmarried and seldom leaves his compound unless it’s absolutely necessary, he depends on his assistant Levinsky to assemble the elements needed to make the story come to life. Finding a sailor willing to take on that assignment is presumably the easy part, so Levinsky saves that for last. Finding a woman who’s both sufficiently beautiful and at ease with the moral laxity that such a task calls for presents the bigger challenge, but all it takes is one. He turns to Virginie Ducrot, played by Jeanne Moreau, a woman who just happens to be the daughter of Clay’s former business partner, a man driven to bankruptcy and suicide by Clay’s treachery. Virginie is indeed gorgeous, but also nervously aware that the bloom of her youth is now fading. Being drawn in by the man she regards as her father’s tormentor for a nauseating but lucrative act of prostitution ratchets up the dramatic tension of the story, and the tale does arrive at a memorable climax, of sorts. But the impact of it all is somewhat muted by flat line readings; distracting make-up and occasionally grandiose staging of the mannered “art house” style in vogue at the time that drains energy from many of the scenes. Welles was aiming to deliver an earthquake, but what most audiences experienced at the time was crickets. Lots of crickets.

It’s natural to wish that Welles would have presented his fans with a more vivid send-off to wrap up his cinematic career, but as it turned out, the essay film F for Fake turned out to be a memorable capstone several years later. I’m sure that at the time he was making it, Welles would have been appalled at the idea that The Immortal Story was destined to be his last literary adaptation for the big screen – especially since the film was expressly created to be shown on TV. As networks in Europe and elsewhere were converting over to broadcasting shows in color, the Organisation Radio-Télévision Française contracted with Orson Welles to create a prestige program that was originally intended to go on the air in the fall of 1967. It seems practically inevitable that in this case, as in so many others, Welles failed to meet his deadline, as his artistic ambitions, his meandering approach to production and the meager resources sent his way so often seemed to conspire against an efficient resolution of his projects. Here, I think we can cut Welles some slack in that he was working in color for the first time, composing for a small screen format (even though an eventual theatrical release was also part of the original plan.) I can also imagine that early audiences were somewhat dismayed by the sight of Welles, physically enormous as he was in both Touch of Evil and Chimes at Midnight, but unlike those roles, here, by comparison, he is now so static and lacking in vitality, a brooding ogreish presence in heavy makeup who mainly just sits in his chair grunting, croaking and glaring at the world from the solitude of Mr. Clay’s withered, miserable existence.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

The new Criterion Collection edition of The Immortal Story just established itself as the preeminent example of what a difference physical media can make in elevating the stature of a film that had previously only been available via internet streaming for most viewers. I watched the film on Hulu a couple years ago, and my experience basically confirmed the mediocre reputation that is reflected in quite a few reviews that preceded the Blu-ray release. Without the enormously helpful context provided by supplemental materials and an insightful commentary track featuring Welles scholar Adrian Martin, a viewer is left unsupported and at the mercy of what looks like a VHS loan from the local library when viewed on the Hulu channel. Thus, it’s rather easy to miss some of the more subtle touches that Welles and cinematographer Willy Kurant bring into play when it comes to the visual aspects of this film. The superb clarity delivered by a new 4K transfer makes an enormous difference, and the convenience of having this film on disc gives us the advantage to replay certain sequences, hit the freeze-frame buttons on numerous occasions whenever we see fit to do so, and find a whole new level of delight in discovering what Orson was striving to communicate to his viewers. I’m extremely grateful that Criterion chose to issue The Immortal Story as a standalone release instead of including it as a supplement or just leaving it on the stream. This feels like an essential acquisition for anyone who has a serious interest in tracking the mercurial career of Orson Welles. And even for those who are not yet fanatical about all things Wellesian (you will be soon enough, if you pay close attention), there is plenty of substantial real life merit here to warrant a closer look.

The fundamental drive behind this production is a contemplation of mortality, and how the art of storytelling offers a prospect of extending the implications of our lives beyond the duration of our physical existence. The character of Mr. Clay, and Welles himself, are both quite aware of the limitations that our feeble, fragile bodies place upon the ability of our minds to influence the world around us. Even those privileged to have vast financial resources (like Mr. Clay) or abundant creative genius (like Welles) must grapple with the barriers that prevent their most heartfelt understanding of truth to be comprehended by the vast majority of humans that they seek to connect with. In Clay’s case, he has made the fundamental decision to detach himself, to basically give up, because the distance between him and the common man has become insurmountable, too painful to contemplate any more than is absolutely necessary. His lifetime pursuit of wealth and power has proven to be fruitless and unfulfilling.

For Welles, I won’t presume that the situation had become anywhere near so desolate and desperate. But he was still aware of the obstacles that stood between him and the masses he sought to reach. The vehicle of story telling, that timeless tradition of one person enthralling listeners with a finely wrought tale that pulls them, even for a moment, out of the space and time they inhabit into a broader realm of imagination and new possibilities, is the focus of what Welles had in mind here. Each of the characters spend a significant portion of their time recounting incidents from their past, and its only afterward that a reflective viewer wonders which among any of the tales told might actually be true. Depicting the would-be puppet master Clay’s quietly lethal frustration at the impossibility of faithfully recreating one of the great anecdotes of his era, despite all the meticulous effort put into its planning, makes The Immortal Story every bit as “meta” and futuristic in its self-referential bona fides as the more widely admired and celebrated F for Fake, once the viewer has settled in and calibrated with the slower, and less obviously entertaining pace of the film.

The supplements included on this disc also steer our attention in ways that help us to better appreciate the main feature. Particularly valuable is Portrait: Orson Welles, a documentary shot right around the same time as The Immortal Story and paired with the film in its television debut in September 1968, gives us a candid, creatively rendered look at the man himself at this stage of his life: vibrant, engaged, and intense, always on the verge of bubbling over into laughter that could just as quickly transform into terse contemplation of some dilemma or another related to the human condition. I also enjoyed the interview with actor Norman Eshley, who was recruited to play the part of the sailor seduced by the allure of five guineas and a unique opportunity to become a literal living legend. He serves as a surrogate of what it was like to be thrust almost at random into the working world of Orson Welles at this time in his life. None of these accounts, nor any of the other bonus shorts found on this disc, bring us that much closer to answering all the questions we might have about what made Welles tick. Indeed, they only draw us further into the mysteries. But that’s exactly what makes this disc such an enjoyable resource to delve into… a story worth revisiting every now and then.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- wellesnet

- New York Times (1969, reviewed as part of a double feature with Luis Bunuel’s Simon of the Desert)

- Cinepassion

- Cine-vue

- Criterion Confessions

- Cut Print Film

- DVD Blu Review

- DVD Verdict

- Eye for Film

- Ozu’s World

- Rough Cut / cageyfilms

- Senses of Cinema

- Slant

Previously: Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell

Next: L’enfance nue