David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

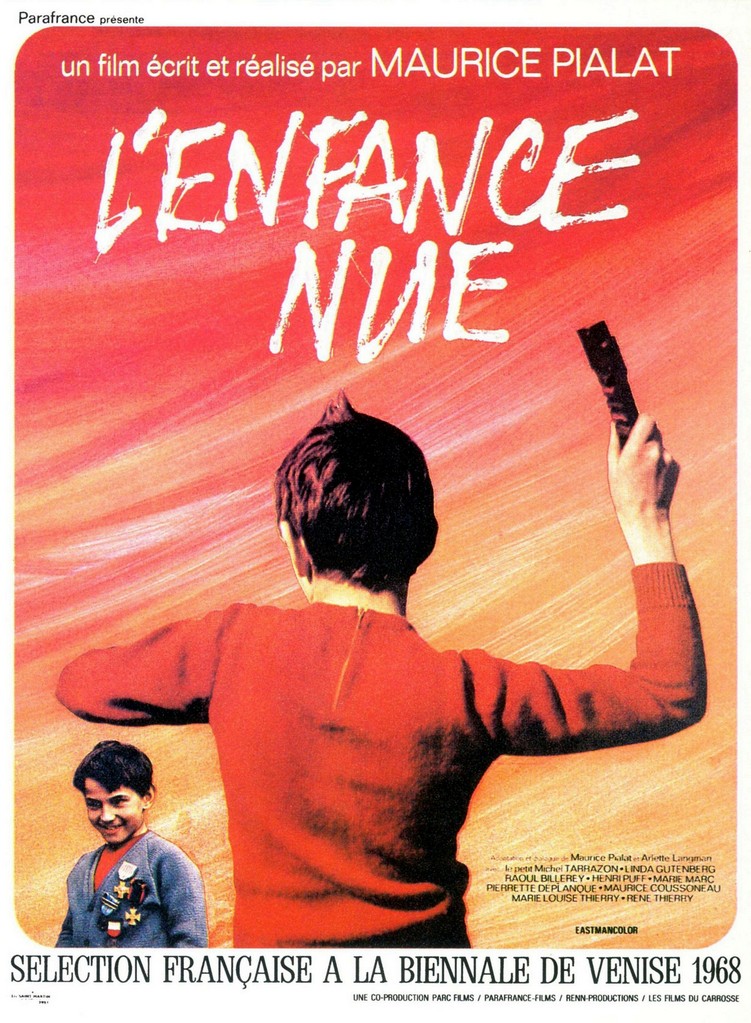

L’enfance nue (translated into English, “Naked Childhood”) consists of a series of sharply observed and well-chosen moments in the troubled life of Francois Fournier, a ten-year old ward of the French foster care system. Director Maurice Pialat made his feature debut, with the support and assistance of Francois Truffaut and Claude Berri, among others, presenting a story that some might find reminiscent of The 400 Blows but without the romantic charm and lovable mischief we associate with Antoine Doinel. (There are no picturesque romps through the streets of Paris or heroic-epic pilgrimages to the ocean in this one, though there is a mad dash tracking shot of a kid nursing a sprained wrist after he’s tossed to the ground following his assault of one of his peers.) Here, the cast is populated by ordinary people in the most quotidian situations, with a story told in elliptical style. Hard cuts jump us from one moment to another after significant changes and developments have taken place in characters’ emotional connections with each other over an indeterminate amount of time. Brutal and senseless acts of childhood violence erupt without warning, context or explanation, harsh enough in their callous cruelty to make a viewer genuinely angry at a child who seems old enough to know better but obviously is missing key empathetic connections (even though he appears to show a caring, affectionate side of himself from time to time.) L’enfance nue is a low-key and easy to overlook title in the Criterion Collection, one of the last films they offered as a DVD-only spine number, but very deserving of attention for anyone who enjoys a clear-eyed, reality based portrayal of real human concerns presented in a context free of sentimentality or easy moral platitudes.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

The opening scene places L’enfance nue directly into the now-historic, then extremely contemporary situation of large organized street protests of laborers demanding justice and reform from their government. After that brief sequence runs its course, issues of fair wages and increased job opportunities recede from the story, but the demonstration underscores the fact that this is a milieu of people struggling to make ends meet, scratching out whatever modest comforts they can from a constricted flow of resources.

Pialat claimed that his intentions for L’enfance nue were not to create an outcry for social justice or advocate for major changes in France’s child welfare system, and that should be clearly obvious to most viewers in any case. He eschews any suggestion of a solution to the problems faced by Francois or others like him. The boy is maddeningly difficult to figure out. He’s impulsive and unpredictable, blind to the damage that his penchant for random cruelty can inflict on others, seemingly craving a sense of belonging and security, but quickly prone to sabotage whatever meager chances he might have at improving his lot in wicked behaviors that don’t even offer anything in the way of temporary satisfaction. Pialat’s objective in all of this is certainly to draw the attention of his viewers to the fact that children like this do exist in the society they live in, and perhaps at some level to point out the inadequacy of the solutions that this same society has managed to come up with. But it feels to me like his vision transcends the problems of youth – he’s out to depict something even more deeply dysfunctional, a conflict more trenchantly irresolvable, within the basic human condition. And in that sense, this film is truly timeless and inexhaustibly relevant to the concerns of our times, and presumably decades, even centuries, to come.

And with a feature debut issued in late 1968, Pialat can rightly be considered a “post nouvelle vague” director, an important distinction as figures like Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, et al. had by this time become part of the mainstream of French cinema in their own way. (Godard was of course breaking off into uncharted territory, but he was in any case no longer part of a new wave…) Pialat shows himself to be completely unconcerned with paying any kind of tribute to the history of cinema, whether it originated from Hollywood or any other territory. L’enfance nue feels particularly set in the moment it was created, incorporating elements of direct cinema and impromptu hand-held camera techniques being used at the time in documentary films, even though they’re employed in a fictionalized scenario. And in this case, many of the scenes are unscripted, with the actors simply being given a description of the circumstances in a given scene and permitted to come up with whatever spoken words seemed appropriate to them at the moment. The midshot framings are effectively accurate, keeping us at an observational distance, refusing to seduce us with close-ups that linger on a character’s emotional interiority. We have to use our own empathetic intuition to identify as best we can with the struggles captured on screen, and some scenes it’s easier than others. The technique is formally sound, a lack of craft never gets in the way, but neither is Pialat going anywhere out of his way to make his audience feel at ease. This is the kind of film that critics and devoted cinephiles of a more acerbic temperamant will appreciate more than the general viewer. And that’s probably why Maurice Pialat is far from a household name, even in art house circles.

This trailer, created prior to the film’s release, actually does a disservice to L’enfance nue in my opinion, by dressing up the footage in a swelling melodramatic musical soundtrack and introducing heart-tugging voice-over narration that Pialat never employs in the finished work. But this is how it was sold to audiences at the time:

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Speaking of “naked childhood,” I wrote a review of L’enfance nue way back in 2010, when I was still a naive and callow young man, just getting started as a contributor to CriterionCast.com. It was a new release at that time, and having just re-read the article for the first time since I published it, I think it still holds up fairly well in summarizing my thoughts on the film, so I’ll advise you to follow the link if you want to read more of what I have to say about it. I’ll just add here that I have a strong fondness and affinity for films like this – not so much the vaunted/dreaded “coming of age” stories, more like “the kid’s messed up and we’re at our wits end trying to figure out how to help” variety.

Criterion has a considerable subset of such films in the Collection. One that clearly comes to mind now is The Kid With a Bike, from 2011, directed by the brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. The strong thematic resonance between that film and L’enfance nue shouldn’t be interpreted as an indictment that “nothing has changed” over the 43 years that separate them as much as it reinforces the intractable nature of the problems these movies portray. (The cover art for both films even seems to suggest a 2-disc box set.) I work with behaviorally challenging children of this sort in my day job, not so directly any more, but I do consult closely with the staff who have the responsibility of finding ways to connect with young people whose trauma and emotional dislocation have stirred up powerful irrational outbursts of aggression and self-harm. Because these kids create so many problems for themselves and others, they’re often sent away into secured settings where in the experience of many, they’re now “out of sight and out of mind.” I always appreciate the opportunity to recommend this kind of film to anyone who might not otherwise have a chance to connect with the plight of abused or neglected children. Especially when the presentation is as clear and unaffected by sap as L’enfance nue – that unique straight-on approach makes this an important film deserving of more attention.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

Maurice Pialat:

- Film Comment (Kent Jones)

- The New Yorker (Richard Brody)

- Harvard Film Archive

- BAMPFA Retrospective

Reviews of L’enfance Nue

- Cineoutsider

- Film International

- Film Forward

- Movie Martyr

- Only the Cinema

- Ruthless Culture

- Slant

- Strictly Film School

Previously: The Immortal Story

Next: Beyond the Law