David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

Profound Desire(s) of the Gods is a sprawling, disturbing, ambitiously weird would-be epic about a clash of societies within the territorial boundaries of a rapidly modernizing Japan. It’s set on the fictional southern island of Karuge, where ancient tribal customs and animistic worship rituals still held most of the inhabitants in a strong (though inevitably loosening) grip. The narrative conflict stems from outsiders who want to convert the arable land into a sugar cane plantation and exploit the island’s inherent value as a tourist destination. But the forces of commerce and technological efficiency are ill-prepared to deal with the stubborn resiliency of the people they encounter, or the baffling complex of myths and taboos that compel them.

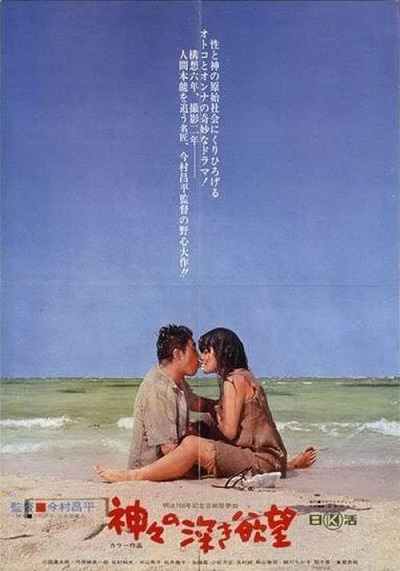

The film was a major throw down by Shohei Imamura, a director who had achieved enough commercial success with his earlier explorations of the more grotesque elements of Japanese society in films like Pigs and Battleships, The Insect Woman, Intentions of Murder, and The Pornographers by convincing Nikkatsu Studios to provide financial backing for what was indisputably his boldest and riskiest project to date.to earn significant funding support from his studio. Using the resources at his disposal, he created a film that was guaranteed to offend and provoke his viewers, asking uncomfortable questions and putting audiences into an awkward space about who, if anyone, they should be cheering on as the raucous, disturbing story line unfolds. Currently only available on Criterion’s Hulu channel, Profound Desire(s) of the Gods definitely deserves to be released on Blu-ray, (it is currently available in Region B through Masters of Cinema) with the full benefit of supplements and a top-shelf transfer, as this is a visually sumptuous feast.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

This is a hard question for me to answer, but as far as I can tell, the film under-performed at the box office upon its initial release, even though it did win some awards from the critical establishment in Japan the following year. This included a submission as Japan’s official entry into the Oscars competition for Best Foreign Language Film, though the Academy did not accept the bid. So my hunch is that mainstream audiences probably found the film too demanding and unsettling to recommend to friends and generate positive word-of-mouth, while those more aesthetically inclined recognized the inherent quality and power of Imamura’s statement, along with the utterly unique and inimitable aspects of a film that captured a transformative moment in Japan’s cultural development, especially as it affected the lives and sensibilities of its dwindling aboriginal subcultures.

The failure of Profound Desire(s) of the Gods to catch on with the general public did have the unfortunate effect of sending Imamura into a bit of a retreat where he focused on small-scale documentary work, as Japanese cinema steered off into more flatly predictable directions, but he was not finished altogether, as he would eventually return to direct a succession of excellent features, including Vengeance is Mine, The Ballad of Narayama, Black Rain and probably several others that I don’t know all that much about at this moment.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

I’ve been stuck on Profound Desire(s) of the Gods for a few weeks now, unsure of just how much time and effort I need to invest in order to properly understand and write about this movie. It’s quite clearly a masterwork, though rendered somewhat unwieldy to summarize due to its perverse subject matter, protracted length and remote setting in an exotic, tropical locale and culture that relatively few viewers have any ability to personally interact with.

Despite all that, a dedicated observer can find so much to enjoy here: beautiful, vibrantly colorful widescreen cinematography that’s deployed to present a fascinating document of culture clash between technologically advanced, money-driven modernity and the raw physicality and emotional bondage inflicted by indigenous tribal customs. The performances, presumably by a largely native and relatively amateur cast, and the abundance of atmospheric elements depicting southern Japanese island life are wildly exquisite and rather unique. I feel confident in asserting that most viewers have never seen anything quite like this spectacle that Shohei Imamura unleashed in the summer of 1968.

So my recommendation comes with a hefty qualifier: this is a brilliant, memorable and affecting film, but it’s likely to challenge and offend most anyone who pays close attention to what’s going on and the psychic toll being inflicted on the central characters. With a nearly three-hour running time, a lot of territory is covered, and it’s explored in relatively leisurely detail, which may create a feeling of narrative drag, at least upon first watch.

(About the title – I’ve seen it translated both ways, as Desire (singular) and Desires (plural) and I’m not sure which is more accurate. I suppose that it does make a difference whether the gods have just one profound desire, or many! I just don’t know what Imamura intended.)

The story initially concerns an eccentric island family, the Futori, that consists of several volatile personalities:

• Yamamori, the selfish elderly patriarch who abuses his authority and knowledge of native lore to justify his own depraved exploitation of his children;

• his son Nekichi, who’s fallen badly out of the old man’s behavior (and who was born of an incestuous relationship between his father and the father’s now deceased daughter – so that the son’s mother is also his half-sister.) The disfavored son has been condemned for dishonoring his family by using dynamite as a shortcut for his midnight fishing activities and is now bound by leg irons to dig out a pit below a monstrous boulder that, once loosed, will unblock a freshwater spring that the islanders desperately need to revitalize their dwindling sources of hydration.

• Uma, a female shaman, daughter of Yamamori and lusted after by her brother Nekichi, for whom she feels a romantic love but refuses to indulge his advances to avoid risking further contempt by the other islanders;

• Kametaro, son of Nekichi (I’m not sure who his mother is) who seems the most psychologically normal of the bunch, mainly because he’s a simple laboring man who just wants to find a way to get off the island and get away from the madness that has swallowed up his family;

• and Toriko, the youngest female descendent of the clan, who suffers from cognitive disabilities due to multi-generational inbreeding. Most likely in her late teens or early twenties, Koriko is well known by the islanders for both her sexual promiscuity and her behavioral volatility.

For the most part, the other natives (inhabitants of a fictional island called Kurage, reportedly based on Okinawa) are portrayed as basically level-headed common folk doing their best to balance out the traditional way of life they’ve grown up with and the changes they see coming and already experience as corporations from Japan’s mainland move in to capitalize on the resources they identify there – productive sugar cane plantations and a potential tourist trade, once the necessary amenities have been developed for the convenience of travelers.

A pair of other characters needs to be mentioned as well:

- Ryu, the apparent leader of the tribe who’s also assumed the role of chief liaison between the corporation seeing to take over and manage the island’s resources. He’s a manipulative conniver, corrupted by greed and hypocritically positioning himself as a defender of his people’s traditional way of life.

- A handicapped singer who is given a name in the film but I can’t find it right now (sorry), who serves as a chorus of sorts, periodically croaking out strategic bits of the mythic origin story of how the island was created, through the erotic union of brother and sister gods, just the kind of cultural subtext that drives and informs the warped incestuous ties that bind the Futori family, and in a sense, the rest of the native population. This aspect of the film was a particularly effective reminder to me about the importance of the origin stories we tell ourselves, about who we are, where we came from and the direction of the society we inhabit, as these stories really do have a profound effect on our lives, and our desires. In a culture populated with so many competing narratives, we do have a responsibility to think through which stories we listen to, accept, and act upon in our personal relationships with the world around us.

Into this potent, lurid hothouse atmosphere enters the engineer Kariya, charged by his bosses in Tokyo to get a handle on this sprawling ungainly project that’s been slowed down by the aforementioned lack of a reliable freshwater supply and the messy superstitions and customary obligations that distract the local hirelings from becoming the efficient drones that help pad the bottom line. Kariya initially presents himself as The Man In Charge, but soon finds himself overwhelmed by the raw seductive power of the culture and people that he’s been paid to subjugate. His entanglement with forces beyond his comprehension is intended to roughly approximate the bewilderment and vulnerability that audiences might feel as they immerse themselves into the environment that Imamura and crew create on the screen. For those who are willing to go along for the the ride, Profound Desire(s) of the Gods should prove to be a striking and unforgettable experience. But I’m pretty sure that there continue to be a fair number of potential viewers who wouldn’t enjoy their time on this island, and who’d be scrambling to get on the next boat back to the mainland as soon as their passage arrives.

I really do hope that Criterion releases this one someday… maybe they’re waiting for a 4K restoration to happen? I’d love to discuss this one on a podcast in the relatively near future.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

Previously: Kill!