David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

Zatoichi and the Fugitives, the 18th installment in the series, is pretty solid overall, a well-made and swiftly paced action-adventure that adheres pretty closely to the standard Zatoichi formula. Once again, the ever-wandering blind swordsman gets drawn into a cruelly unbalanced conflict between merciless criminals and honest village folk who are just trying to trudge a path through life that keeps their suffering to a minimum. If allowed to pursue their brutal agenda without interference, the bosses will grind their subordinates into the dust and inflict a lot of personal anguish upon them through various acts of robbery and exploitation. Zatoichi recognizes the bestial nature of the men in charge and reluctantly takes it upon himself to defend the weak and vulnerable. I like these stories because of their relatively pure and straightforward approach to the heroic formula. That’s kind of a rare thing to see in films these days as even the most traditional of such figures (Superman, Batman, the Marvel characters, etc.) are all so weighted down in contrived ambivalence and ham-handed explorations of internalized psychological conflict that it’s hard to just sit back and enjoy the show. But I digress.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

There isn’t all that much I can see here that places the film more in “1968” than in any of the other years that immediately preceded or followed it, so I can’t comment much on that point. But my hunch is that this was probably viewed by fans of the franchise as a successful entry that incorporated timeless themes into its narrative. Beyond the generic structure I mentioned above, this story touches upon unresolved conflicts within families – a father who’s disowned his son for inexcusable acts of violence that violate the patriarch’s ethical code and a daughter/sister who is desperately trying to work out reconciliation between the two stubborn men before it’s too late.

There’s also a thoughtful portrayal of a young woman who gets mixed up with the wrong sort of guys as her traveling companion and quickly finds herself enmeshed in plots of violence and corruption that are too entangled for her to escape – until Zatoichi’s flashing sword arrives on the scene to cut through the knots and give her a chance to start a new life for herself. (He kind of forces her to that option anyway, since all of her traveling companions get hacked up before the film reaches its grim inevitable conclusion.)

You can hear Shintaro Katsu (star of the series for those who don’t know him by name) sing his evocative theme song starting around the 3:30 mark in the clip above.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

There are two aspects of the film that make it somewhat distinctive from the others, in my mind anyway. One is the continued escalation of violence and cold-hearted viciousness on screen – we get more blood-spurting, severed limbs and gleeful sadistic mayhem with each passing episode by this point in the series. If it hadn’t been titled Zatoichi and the Fugitives, they could have gone with “Zatoichi Bleeds” and scored 100% on the truth-in-advertising fact checker. I expect that this trend of making the protagonist pay a higher physical and spiritual price following his innumerable conflicts will continue, as Zatoichi’s character seems to have veered away from the more comedic takes of a few titles from mid-series into a sustained study of man who’s enduring profound loss, pain and estrangement with each new twist on his journey.

But the main attraction here is the presence of Takashi Shimura, the great leading man from so many of Akira Kurosawa’s films of the 1940s and 50s (Stray Dog, Ikiru, Seven Samurai and so many others), before the roguish vitality of Toshiro Mifune pushed Shimura’s aging profile into the background of Kurosawa’s late 50s masterpieces. Here he plays a kindly old doctor, his distinguished silver hair pulled back into a modest pony-tail, and it’s a fine role for the venerable actor. His familiarity as an icon of stoic compassion and world-weary wisdom in so many of his previous roles serves him and the audience well, as he hardly needs to emote all that strenuously for us to instantly understand his good intentions and the presumable burden of suffering and endurance that he has learned to carry in order to serve the hard-pressed inhabitants of this humble agrarian village.

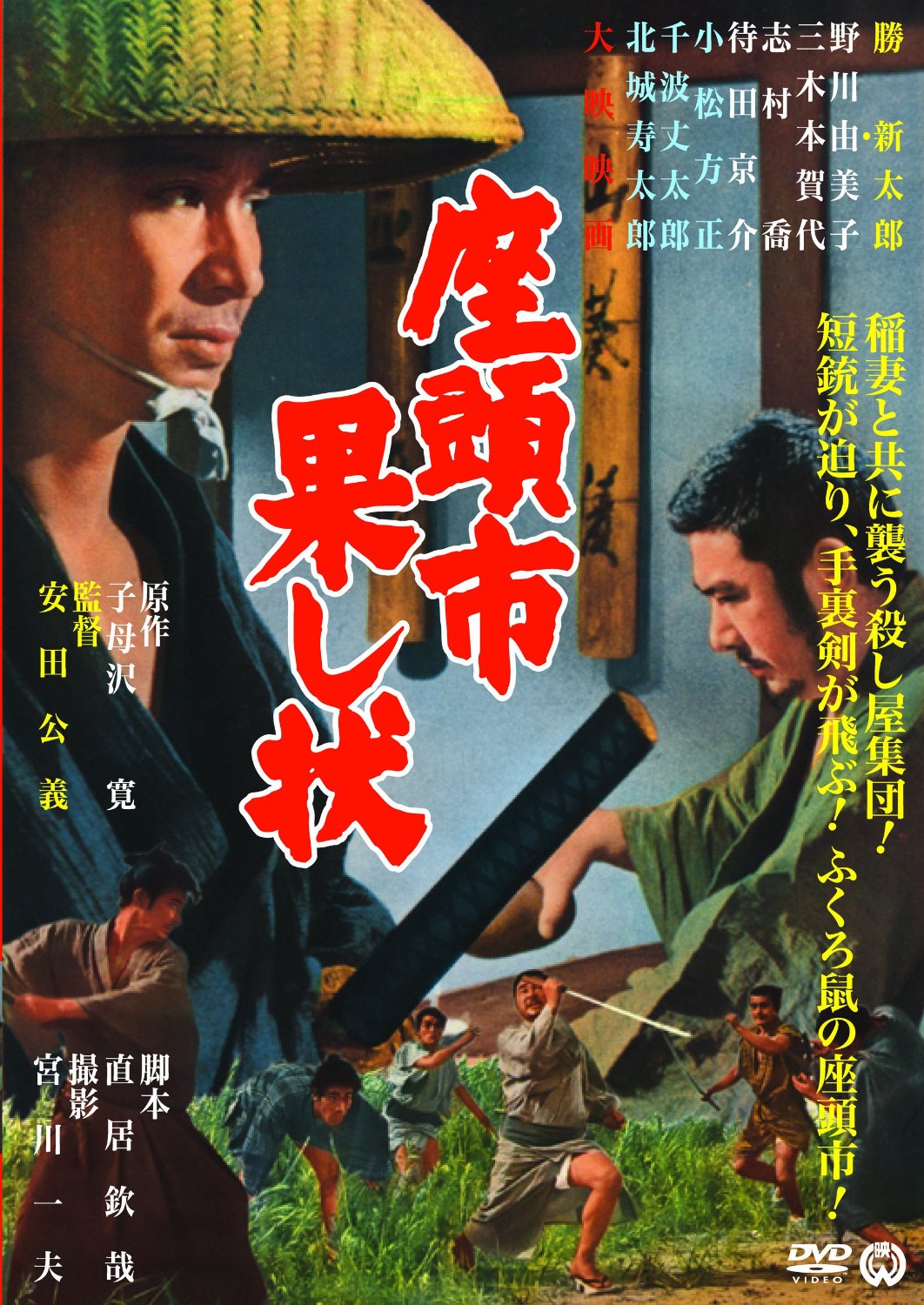

It strikes me as kind of crazy that Shimura only gets fourth or fifth billing here (I’d put him right up behind Shintaro Katsu, but that’s just me). And he’s not even featured on the poster! I suppose his star power had faded by that time, and maybe in 1968 he wasn’t quite regarded as the living legend that I and many others regard him as in the 21st century. (Well, he’s no longer living, of course.) Back then, he was probably just another old actor still kicking around, popping up in movies every now and then, aging gracefully. And this is hardly an elegiac role – he’ll be back in a few years, appearing as a different character in another installment (Zatoichi’s Conspiracy), so lets see if they come up with a new hairstyle. But in any case, I especially enjoyed all the scenes that he appeared in, just because he’s Takashi Shimura. Enough said!

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

I also want to give a special nod of affirmation to a couple of guys who just started doing The Blind Podsmen podcast, a series dedicated to discussing the Zatoichi series in all of its various incarnations. They’re going into this set of films fairly blind (as they explain in their introductory episode.) As of today, they’re only up to #2, The Tale of Zatoichi Continues, the last of the monochrome features. So it will be awhile before they catch up with me, but I admire their ambition and want to encourage them in their effort and perhaps send a few readers here to become listeners there.

Previously: Profound Desires of the Gods

Next: Stolen Kisses