As far as enigmatic movies go, Olivier Assayas’ Clouds of Sils Maria is among the most mainstream, and that definitely isn’t a bad thing. Compared to something like the Dardenne Brothers’ misstep, Two Days, One Night, Assayas’ film uses its star power and the real-life connotations of its subject matter to tell an outwardly casual story that has deep sub-textual ramifications. Vague and guarded when it needs to be, it also manages to be equally melodramatic and external when it wants to be, making for a sly meta-commentary on broad themes like desire, womanhood, obsolescence, waning sexuality, and the bitter pull of Hollywood.

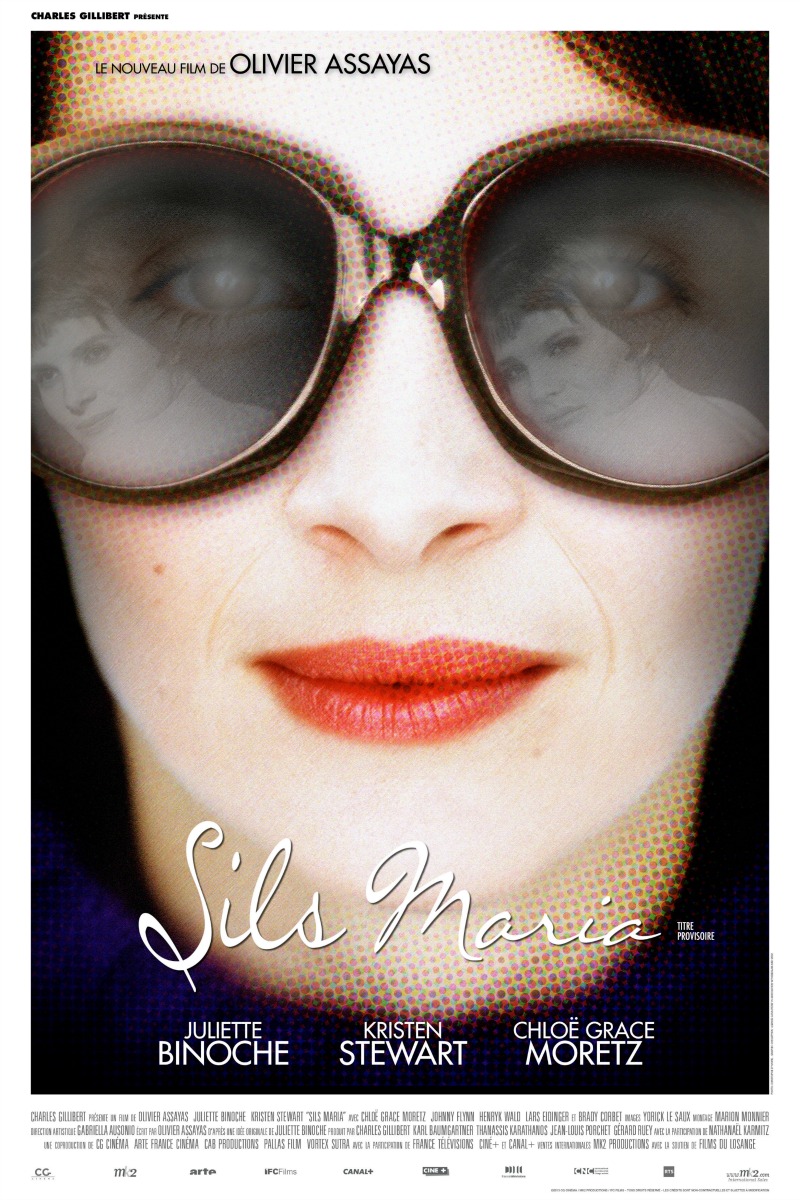

Anchored by two delicately confrontational performances by Juliette Binoche and Kristen Stewart (the latter finally proving she’s more than just a barely-interested tween icon), Clouds of Sils Maria marks a brilliant and moody return to the similar themes Assayas explored in 1996’s Irma Vep. Binoche is Maria Enders, an over-the-hill former French film icon who is approached to star in the remake of the movie that launched her storied career a few decades earlier. Called “Maloja Snake,” the film is a sort of sexual tete-a-tete between an older businesswoman and her dynamic young female secretary who enter into a volatile lesbian affair. Fans of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant will see more than a few the similarities here. Enders ostensibly burst onto the scene playing the precocious secretary—a role that haunts her and preoccupies her memory till this day—but the filmmakers for the remake want her to now reinterpret the older role of the has-been, which was previously performed by a co-star who died in a car accident a year after the original movie was released.

Riding along on Enders’ coattails is her assistant Val (Stewart) who goads Enders into thinking about, and then accepting the new role. The two run lines together, and argue about what each perspective represents to them and the characters. The mirroring and co-dependency between real life and the fiction in the film are not hard to miss. Assayas wrote the 1985 film Rendez-vous, which launched Binoche’s career, and the film-within-a-film conceit works on the film’s obsession with the passage of time and how such a simple thing could effect the vitality of actresses both at the start and in the twilight of their careers.

Much like Binoche’s turn in Abbas Kiarostami’s similarly-meta Certified Copy, the film uses its magnetic leads to seductively pull the viewers in to the film’s mysterious and open-ended psychological underpinnings. Just as you think you’ve got things figured out—insofar as the film needs to be “figured out at all—it seems to dissolve into elliptical directions punctuated by a series of elegant fade-outs that transition us from scene to scene. It is a film that always seems just one step ahead and you’ll gladly let it lead you wherever it wants to go.

Past versus present, real life versus performance, Clouds of Sils Maria blurs the lines between the blurred lines to create a mesmerizing drama of oblique emotions and gorgeous visuals. Its dreamlike quality lulls you into its grasp, and even when it may over step its welcome to become too on the nose it’s still worth keeping up with. Olivier Assayas remains one of the most vital voices in cinema today, and Clouds of Sils Maria is ample evidence of his artistic genius.