If he keeps on the same track with his next movie, Roman Polanski will have carved out a pretty nice late-period trilogy of chamber pieces in his storied career. Following 2011’s Carnage, a film adaptation of playwright Yazmina Reza’s stage play God of Carnage about prickly Brooklynites played by Jodie Foster, Kate Winslet, Christoph Waltz, and John C. Reilly whose petty squabbles escalate into a delightfully buffoonish mix of mouthing off, Polanski is back with a new film Venus in Fur. Much like Carnage, this film is an adaptation of a stage play (of the same name by playwright David Ives) and the main action takes place all within one setting. Whereas Carnage’s theatricality became evident because of its cinematic reworking and thus possibly detracted from the need for such an adaptation, Venus in Fur is essentially unrepentantly theatrical through and through, making it a cheekily layered minimalist film of vibrant energy, wry humor, and clever subtext that is perhaps the best among Polanski’s recent output.

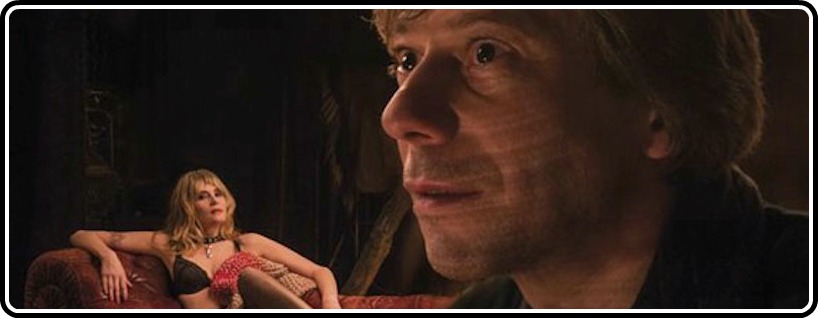

Mathieu Amalric is Thomas, the frustrated writer/director of a new Parisian stage adaptation of the Leopold von Sacher-Masoch novel Venus in Furs to be produced in a small ramshackle theater off the Champs-Élysées. Tired of churning through terrible auditions to find the right actress for the female lead Wanda, Thomas all but gives up before a disheveled but mysterious woman named Vanda (played by Emmanuelle Seigner, Polanski’s real-life wife) shows up to audition for the part. Initially she is unfamiliar with the play and admits to not being prepared, but Thomas gives her a chance anyway. Soon she strangely runs through the play verbatim, and the split between reality and fiction, performance versus actuality begins to blur. The sexually tinged power dynamics of the tête-à-tête between the two begins to unfold.

The film would fall apart if the two characters (the only two in the entire film) weren’t believable, or if the slippery nature of their knowing performances weren’t as deftly handled as Amalric and Seigner manage to make them. It’s a film that hinges on the reconciliation between the ability to recognize histrionics and the ability to carry the concept out, and Seigner’s firecracker of a performance hits every mark. The way she is able to turn the narrative tables for both Alamric’s character and the audience with a winsome look, a giggle, or a glance is an absolute delight.

Of course Polanski’s staging and direction much be mentioned. The old-but-still-kicking veteran has perhaps learned to sheer away certain tendencies that displayed the theatrical shortcomings in Carnage, and instead makes the rapid but contained movements of the two characters and the Karostami-esque meta-narrative in Venus in Fur among its strengths. One could dig deeper into the story and see a little bit of Polanski in the Thomas character—a frustrated and slightly aging playboy director caught up in his own creation. Whereas Thomas gladly submits to the exploration of sexual identity found in the material because he’s a broken person, Polanski is emboldened because he submits to the way in which his previous films inform this one with some of the same subject matter. This is to say that for however much this wouldn’t superficially resemble a quote/unquote “Polanski film,” it most definitely is, and he succeeds.

People will say that this movie is slight in comparison to the greatest hits in Polanski’s career, but if only they’d look deeper they’d see a director with such an assured hand that suggests he doesn’t care about the greatest hits. Polanski is admirably doing his own thing because he’s earned the right to do his own thing, and if it’s churning out adaptations of stage plays then that’s fine with me. If they’re all as good as Venus in Fur then Polanski is most definitely not out of gas one bit.