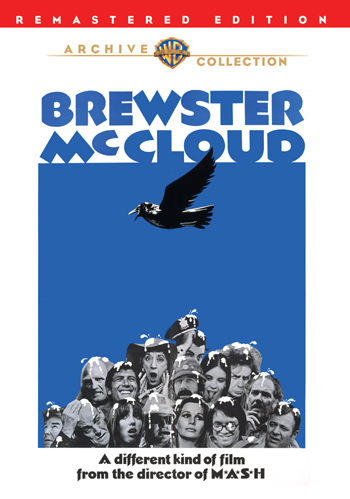

The 1970s was the start of a golden age of American Cinema. Filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma and Francis Ford Coppola paved the way to make American Cinema transcend the box office into artistic expression. Their influence of foreign filmmakers like Kurosawa, Fellini and Godard with the sense of kinetic energy, passion and a disregard for rules and convention could be seen on the screen. Namely in which with Robert Altman who gained stature in 1970 with the extraordinary film, MASH, started a decade of social commentary by way of playful genre. In Brewster McCloud, Altman explores the themes of purpose and an absurd, purposeless world. The once extremely hard to find film (until now the only way to see it was on VHS or in theaters as part of an Altman Retrospective) is now available on DVD for the first time via the Warner Archive.

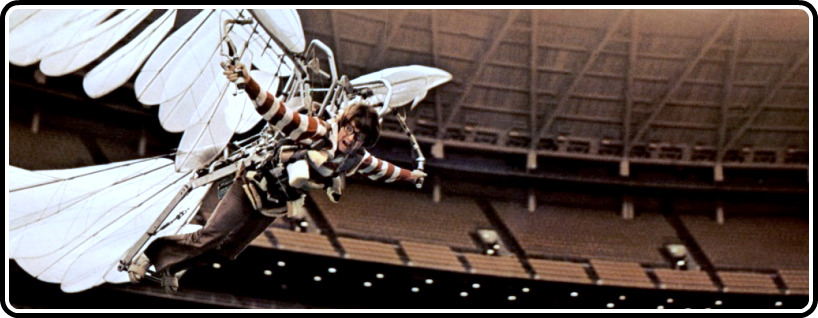

Bud Cort plays the title role of Brewster McCloud, a young, owlish man who lives in a sweaty storage room under the Astrodome in Houston, Texas. He spends most of his days building a pair of mechanical wings in the hopes of one day of flying. This journey takes him through the city of Houston born out of simple, oafish citizens who belittle and mock his attempts and manner. But when Brewster McCloud gets fingered as a serial strangler, the incompetent Houston Police Department can’t seem to catch up with him.

The story is somewhat absurd but I think that’s the point. The ridiculousness of Altman’s cinema is part of the filmmakers charm but in Brewster McCloud, he misses his own mark. Brewster McCloud can easily be seen as a minor work of Robert Altman, and it really is, but what he tries and fails to do in Brewster McCloud, he will later succeed in his future film, Nashville. The film plays like half instructional video (the relationship between the mating patterns of birds and what is on the screen) and half narrative (on the screen). The theme of purpose brought up in McCloud is not as tight as in Nashville. But what doesn’t work is the general randomness of this world. In Nashville, Altman created a familiar world that is slightly skewed by a city that is part of this whimsical world. The sense of anything can happen at anytime doesn’t work when the story is centrally focused rather than in Nashville where the narrative is roaming.

Altman’s camera in Brewster McCloud is his signature. Always roaming and never stale, Altman exudes a curiosity of a world he creates. A very smart and clever filmmaker, Altman is like none other, always bringing the best out of his actors. Bud Cort is wonderful in this film, a prelude to his iconic Harold in Harold & Maude. Playing an introverted young man searching for meaning in his dull life in a nonsensical world. And the introduction of a 20 year-old Shelley DuVall is a revelation and the start of a long decade as a muse for Robert Altman. Her nymphish demeanor is so infectious and lovely, that you can see, it’s the start of a very special career. During the course of the film, I found myself drawn to the performance of the actress Jennifer Salt who plays Hope, a unrequited love of Brewster McCloud. Her performance goes along well with the themes explored in the film and you do get this general sense of attraction and curiosity.

Brewster McCloud is still a work of a master filmmaker and should be viewed as such. For every Goodfellas there’s an After Hours and for every The Godfather there’s a Peggy Sue Got Married. Minor works of master filmmakers are ways to see how they got to be so great. Every time at bat doesn’t mean you have to knock it out of the park but when it does happen it makes it so much more special. Brewster McCloud is not a home run but rather a base hit double through second. A very good effort but doesn’t score a run for the team. And that’s good enough for me.

Brewster McCloud (Bud Cort) lives deep within the cavernous underground of the Houston Astrodome, but his dreams rise much higher. He aims to fly. Not in a plane. But with strapped-on wings he’s … More

Director: Robert Altman

Cast: Bud Cort, Michael Murphy, Rene Auberjonois, Sally Kellerman, William Windom

I’m not sure if I agree that this is a minor work, but maybe we’re bound to differ as I also think After Hours is a masterpiece! Brewster McCloud operates on another more semiotically charged plane of reality to other films. It can’t really be analysed in terms of plot and character development as this would be to limit its appreciation to the banality of cinematic discourse. Its brilliance is in its transcendence of conventional cinematic expression, in it you sense the spirit’s rebellion against the dictates and restrictions of consensus reality and its dreary footsoldiers. If you are sensitive to its suggestions and promptings and are sufficiently aroused, something ineffable, mysterious and infinitely rich is communicated to you that is above and beyond the confines of regular cinematic experience and interpretation.. There is a sense of a profound and enigmatic interconnectedness being expressed, that communicates on a subtle level, somewhere beyond the reach of the discursive and rational mind. There is more here. You could argue that the film succeeds where Brewster doesn’t in that it transcends banality by finding meaning, beauty and mystery in an apparently absurd world. God has spoken and Altman is his mouthpiece.

I’m not sure if I agree that this is a minor work, but maybe we’re bound to differ as I also think After Hours is a masterpiece! Brewster McCloud operates on another more semiotically charged plane of reality to other films. It can’t really be analysed in terms of plot and character development as this would be to limit its appreciation to the banality of cinematic discourse. Its brilliance is in its transcendence of conventional cinematic expression, in it you sense the spirit’s rebellion against the dictates and restrictions of consensus reality and its dreary footsoldiers. If you are sensitive to its suggestions and promptings and are sufficiently aroused, something ineffable, mysterious and infinitely rich is communicated to you that is above and beyond the confines of regular cinematic experience and interpretation.. There is a sense of a profound and enigmatic interconnectedness being expressed, that communicates on a subtle level, somewhere beyond the reach of the discursive and rational mind. There is more here. You could argue that the film succeeds where Brewster doesn’t in that it transcends banality by finding meaning, beauty and mystery in an apparently absurd world. God has spoken and Altman is his mouthpiece.