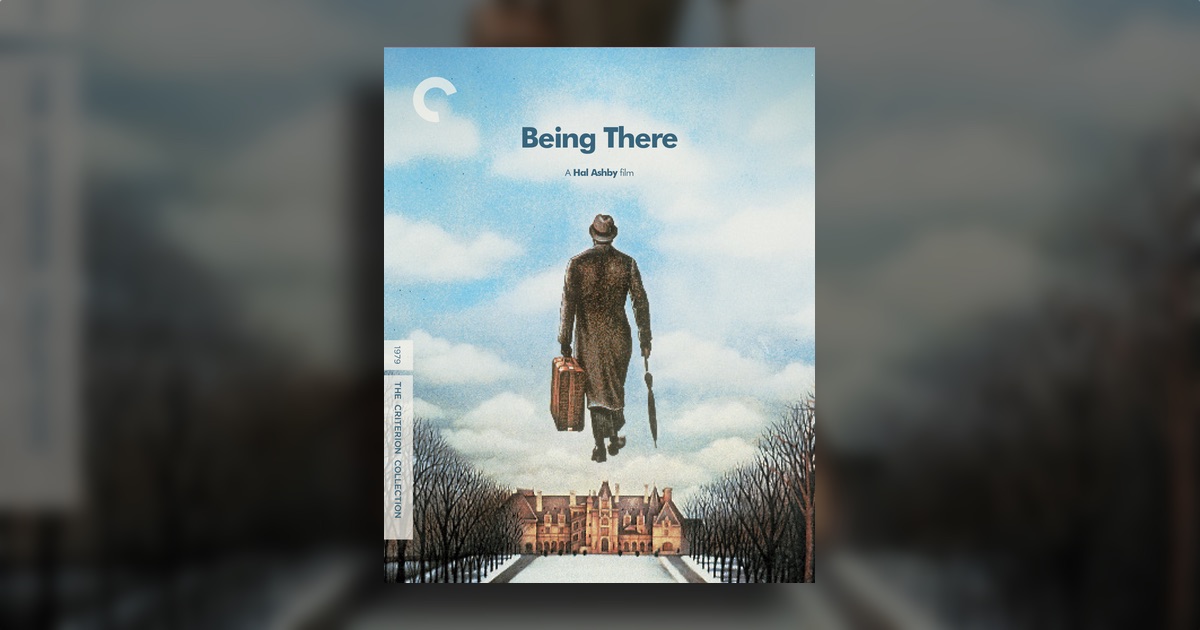

Ever since Warner Brothers released their 30th Anniversary edition Blu-ray of Being There back in 2009, I’ve been tempted to add the disc to my home library. I can recall several occasions where I actually had the case in my hand, and at least one where I took what I would normally consider that first decisive step toward the checkout line, ready to finalize the purchase. But lingering suspicions that this film would eventually find its way into the Criterion Collection always managed to pry the item out of my fingers and back onto the shelf. A few months ago, my reluctance was vindicated by the announcement that Being There would sure enough soon bear a CC spine number, and this past week, it finally became available to take home for the contemplation of all of us who “like to watch.”

Even for viewers who haven’t seen the film in a long time (or ever), Being There‘s underlying conceit, about a a distinguished looking simpleton raised on television whose innocent banal utterances are taken as profound insights by powerful men, has effectively stamped itself on the popular imagination. Primary credit for that enduring success rightly goes to Peter Sellers, for his memorable minimalist portrayal of Chance the Gardener. A man raised in material comfort and social isolation from his youth, deprived of all relational stimulation other than what he gets from watching TV and tending to plants in a walled garden, Chance is loosed upon the world without any preparation for the hazards of modern life. Implausibly stumbling into the uppermost echelons of political influence, his plain manner of speaking and utter lack of pretension are regarded as virtues of sublime rarity in those circles, rather than the crippling social handicaps they actually are. He’s quickly embraced as an important new voice of American leadership as a result.

Sellers gives a performance that at first glance seems rather straightforward and basic. The assignment, after all, is to simply maintain emotional neutrality in all circumstances. But that’s exactly what makes the role so challenging, since it prevents the actor from doing what he normally does best – engaging with his audience on an overtly comedic level. In stripping down all traces of the exaggerated buffoonery and silly vocalizations that he’d become famous for in his repeated turns as Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther franchise, Sellers established a modern template for cinematic idiots savant that was subsequently borrowed by actors like Dustin Hoffman (Rain Man) and Tom Hanks (Forrest Gump), among others less celebrated for their efforts.

Director Hal Ashby also comports himself quite well here, as he capped off an all-but-legendary run of triumphs throughout the 1970s, starting with Criterion title Harold and Maude from 1971 and followed by several others (The Last Detail, Shampoo, Bound for Glory and Coming Home) that would also be good fits for the Collection. Sadly, this would be the last of his films to get much attention, as his drug habits took their toll and an indulgent approach to doing the movie biz made him a misfit in an even newer 1980s version of Hollywood than the New Hollywood in which he came up as a filmmaker. The liner notes by Mark Harris describe Ashby’s career after this point as a “downward spiral” that only ended when Ashby died in 1988, and the supplemental features on the disc do a great service in allowing Ashby to speak for himself, along with others involved with this film who managed to survive the excesses. But in what turned out to be the last cinematic hurrah for both Ashby and Sellers, all the right pieces fell into place, with an excellent cast, a succinct, witty (and largely ghost-written) script and a flourish of sharp artistic touches that offer dividends upon repeat viewing: a smartly curated stream of video clips and advertising jingles running throughout the film that comprises an effective A/V time capsule of the era’s mediascape, and a musical set piece that winks at Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, easily my favorite sequence in the film:

Of course, complaints about a culture dumbed down through the nefarious influence of TV networks that feed pablum to the masses had already approached the status of a cliché by the end of the 70s, so the initial and on-going success of Being There is attributable more to the clarity of how it framed and delivered that message, than in how original it was in making the general observation. What struck me more vividly upon my most recent viewing, with an insight that apparently slipped past my younger self, had to do with how the stage for the gardener’s rapid ascent to fame and insider status was due to what we’d now refer to quite plainly and accurately as white male privilege. It comes out most vividly in the comments made by Louise, the black maid who had to leave her employer’s DC mansion after he died, when she incredulously sees Chance on TV being touted as a man of gravitas and substance, but also very briefly (and just as vividly) in a scrawl of graffiti that appears to have been slightly censored in the above clip, since we never see the full statement “AMERICA AIN’T SHIT CAUSE THE WHITE MAN’S GOT A GOD COMPLEX” in one unmissable frame, as we do in this Blu-ray edition. I can imagine why it might have gotten oh-so-slightly snipped in the process of being edited for television, or even for earlier home video releases.

Being There was released in December 1979, a month or so after Ronald Reagan had been elected to succeed Jimmy Carter as President of the USA, and a month or so before he took his oath of office. Though the film had been in development for several years, and production was well underway back when Reagan appeared to be an electoral longshot, the timing still seemed uncanny for the moment it inhabited. The parallels were easy to draw then, as Reagan’s well-crafted method of delivering folksy quips and catchphrases came across to many as a slightly more sophisticated (and more cynical) echo of what happened to Chance when he assumed the national stage as “adviser to the president” Chauncey Gardiner.

Now, in the early months of the Trump presidency, as our country and the rest of the world grapple with the reality of another media-saturated brain seemingly wielding more clout than seems healthy for any of us, this new release has been widely perceived as a commentary of sorts on contemporary politics. Speaking for myself, and presumably many others, I’d easily feel more comfortable placing a genteel enunciator of empty platitudes like Chauncey Gardiner in the Oval Office than I am with its current occupant. We don’t know how long Criterion had been working on this new release before they announced it this past December, just five weeks after that shocking Election Night the previous month. But the coincidence with current events created a clearly detectable line of cause-and-effect among many of us close observers of all things concerning the Wacky C. Perceptions are reality, as they say. Or to put it another way, as the movie president quoted his new confidante in the film’s closing moments…