Podcast: Download (234.8MB)

David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

My quick take on 2001: A Space Odyssey is that, after carefully rewatching the film and reading a fair amount about it over this past week or so, I arrived at the conclusion that it’s my favorite movie of all that have ever been made. I have said the same thing in the past, but that was many years ago, long before I had become familiar with so many classics of world cinema and Hollywood’s past that preceded my birth. My deep immersion over the past decade into a self-directed study of film history led me to temporarily suspend judgment on so momentous a question as what I consider to be “the greatest film ever made,” but now I’m pretty comfortable with saying that it’s this one, without any doubt on my part. That’s subjectively speaking, of course, since the debate can never be definitively, authoritatively settled. But 2001 is the number where I’m willing to put down my chips and make a declaration. I’ll make the case below, perhaps not exhaustively or with a serious intention of persuading the skeptics or others who might disagree. But in quick summary, I just love everything about this film:

- the themes of humanity’s quest to discover our purpose and control our destiny

- the impeccable visual style

- the emotive power of the music and sound design

- the aura of cosmic mystery

- the fascination with science and technology

- the majestic eon-spanning scale of the story from our distant past to a possible future

- and the incredible realization of so many visionary ideas on a practical and artistic level that went into the film’s creation

This is a masterpiece that speaks to me in so many ways, and brings me fresh feelings of delight every time I encounter it again.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

The making of 2001: A Space Odyssey was already a subject of great interest well before the film had been released. Stanley Kubrick’s previous film Dr. Strangelove (soon to be re-issued in a new Criterion edition) had been a commercial and critical hit in 1964, and it was apparent that his bold and singular talent warranted close attention. A press release in February 1965 announced that Kubrick would partner with noted science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke to shoot a film titled “Journey Beyond the Stars,” set in the year 2001. The timing for a serious, big budget film treatment involving exploration of the solar system could not have been any better, as the NASA space program was ramping up its efforts to fulfill the ambition of the slain US President John F. Kennedy to put a man on the moon by the end of that decade, and for the most part, the American public was enthusiastically on board with the project.

As a genre, science fiction was still locked in a stereotype of cheap drive-in fare, B-movie silly kid stuff as far as most film studios were concerned. But the development of rockets that routinely ascended above the atmosphere, carrying men safely into orbit and back home again, piqued the nation’s curiosity about just how far this new mode of transportation would take us. Over the next few years, Kubrick and his cinematic work in progress were the focus of stories in Look and The New Yorker magazines. A 1966 documentary titled 2001: A Space Odyssey – A Look Behind the Future gave viewers an enticing glimpse into what Kubrick, Clarke and their crew had in store for them when this lavish, expensive and groundbreaking production finally hit the big screen. The collaboration promised to offer more than just an informed speculation on how astronautical science might progress. It would press even further into the moral and philosophical implications of humanity’s expanded awareness of the vast universe that they inhabited.

A pocket-sized paperback book titled The Making of Kubrick’s 2001 (edited by Jerome Agel) was the first of several successively more expansive volumes written over the years dedicated to gathering up a generous sampling of the textual and photographic records of its production. Published in 1970, it’s a wonderful archive of first responses to the film, along with the requisite behind the scenes anecdotes and trivia. Dozens of reviews are included, either in full or (more often) in salient excerpts, some by prominent critics of the time, others by ordinary viewers from all different walks of life. Among the scattered outbursts of feverish adulation, a few indignant requests for refunds or other scathing insults, and several thoughtfully rendered interpretations from viewers eager to receive feedback from the master Kubrick himself (which he generously provided in at least a few instances), here are a few samples that struck me as particularly interesting due to the enduring fame and reputation of the person being quoted:

- “YOU MADE ME DREAM EYES WIDE OPEN STOP YOURS IS MUCH MORE THAN AN EXTRAORDINARY FILM THANK YOU” – Franco Zeffirelli

- “I SAW YESTERDAY YOUR FILM AND I NEED TO TELL YOU MY EMOTION MY ENTHUSIASM STOP I WISH YOU THE BEST LUCK IN YOUR PATH” – Federico Fellini

- “May I offer my congratulations for a marvelous picture. Once again you have given us all something to aim at.” – Richard Lester

- “I saw your film and just wanted you to know how beautiful and exciting I found it. Apparently most everybody else does, too, even those few who worry about your ending. For me it was a fascinating, breathtaking experience.” – Saul Bass

- “It was e.e. cummings, the poet, who said he’d rather learn from one bird how to sing than teach 10,000 stars how not to dance. I imagine cummings would not have enjoyed Kubrick’s 2001, in which stars dance but birds do not sing.” – Roger Ebert

- “The issue is simply that, on this occasion, Mr. Kubrick was unable to translate his ideas into adequate patterns of expression, and that’s all there is to it. It doesn’t mean that it would have been a better film if everybody on the Metro lot had been able to give his opinion of what was going on and suggest improvements and so forth. It think it would have been a much bigger mess than it turned out to be.” – Andrew Sarris

- “It’s fun to think about Kubrick really doing every dumb thing he wanted to, building enormous science fiction sets and equipment, never even bothering to figure out what he was going to do with them. In some ways, it’s the biggest amateur movie of them all, complete even to the amateur-movie obligatory scene – the director’s little daughter (in curls) telling daddy what kind of present she wants. It’s a monumentally unimaginative movie.” – Pauline Kael

- “It is morally pretentious, intellectually obscure, and inordinately long. The concluding statement is too private, too profound, or perhaps too shallow for immediate comprehension.” – Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

- “The pictorial part was superb. The color photography was generally excellent and the special effects and technical tricks were the best ever done. But Kubrick and Clarke gave us dullness and confusion… This isn’t a normal science-fiction movie at all, you see. It’s the first of the New Wave-Thing movies, with the usual empty symbolism. The New Thing advocates were exulting over it as a mind-blowing experience. It takes very little to blow some minds. But for the rest of us, it’s a disaster. It will probably be a box-office disaster too, and thus set major science-fiction moviemaking back another ten years. It’s a great pity.” – Lester del Rey, Galaxy magazine.

- “Were 2001 cut in half it would be a pithy and potent film, with an impact that might resolve the ‘enigma’ of its point and preclude our wondering why exactly Mr. Kubrick has brought us to outer space in the year 2001… We hope he just sticks to his cameras and stays down to earth – for that is where his triumph remains.” – Judith Crist

- “On the trip out, the music of the spheres turns out to be Muzak – lush and mindless reiterations of “Blue Danube Waltz” … The theme of the film: man’s vaulting ambition is matched by nothing approaching the necessary qualifications and man’s outreaching himself is, at once, noble, funny, stupid, and sad.” – Donald Richie

- “I don’t like 2001 completely. It’s very beautiful visually and technically as a film. But I don’t agree with Kubrick. I don’t understand exactly what he’s saying about technology. I think he’s confused.” – Michelangelo Antonioni

- “Clarke, a voyager to the stars, is forced to carry the now inexplicably dull director Kubrick the albatross on his shoulders through an interminable journey of almost three hours… Clarke should have done the screenplay totally on his own and not allowed Kubrick to lay hands on it. Technically and photographically, it is probably the most stunning film ever put on the screen… The test of the film is whether or not we care when one of the astronauts dies. We do not… The freezing touch of Antonioni, whose ghost haunts Kubrick, has turned everything here to ice.” – Ray Bradbury

- “A movie like 2001 belongs to 1901, or even to the world of Jules Verne. It is filled with nineteenth century hardware and Newtonian imagery. It has few, if any, twentieth century qualifications. This is natural. The public is not capable of being entertained by awareness of its own condition. Fish do not care to think about water, or men about air pollution.” – Marshall McLuhan

I’ll post a few other extended reviews included in the book in the Links section below, though the selection is dependent on what I can find on the web. I highly recommend this paperback though for anyone as fascinated by this film as I am. I was fortunate to find a copy at a library clearance sale for fifty cents. It runs closer to $20 on the secondary market on Amazon.

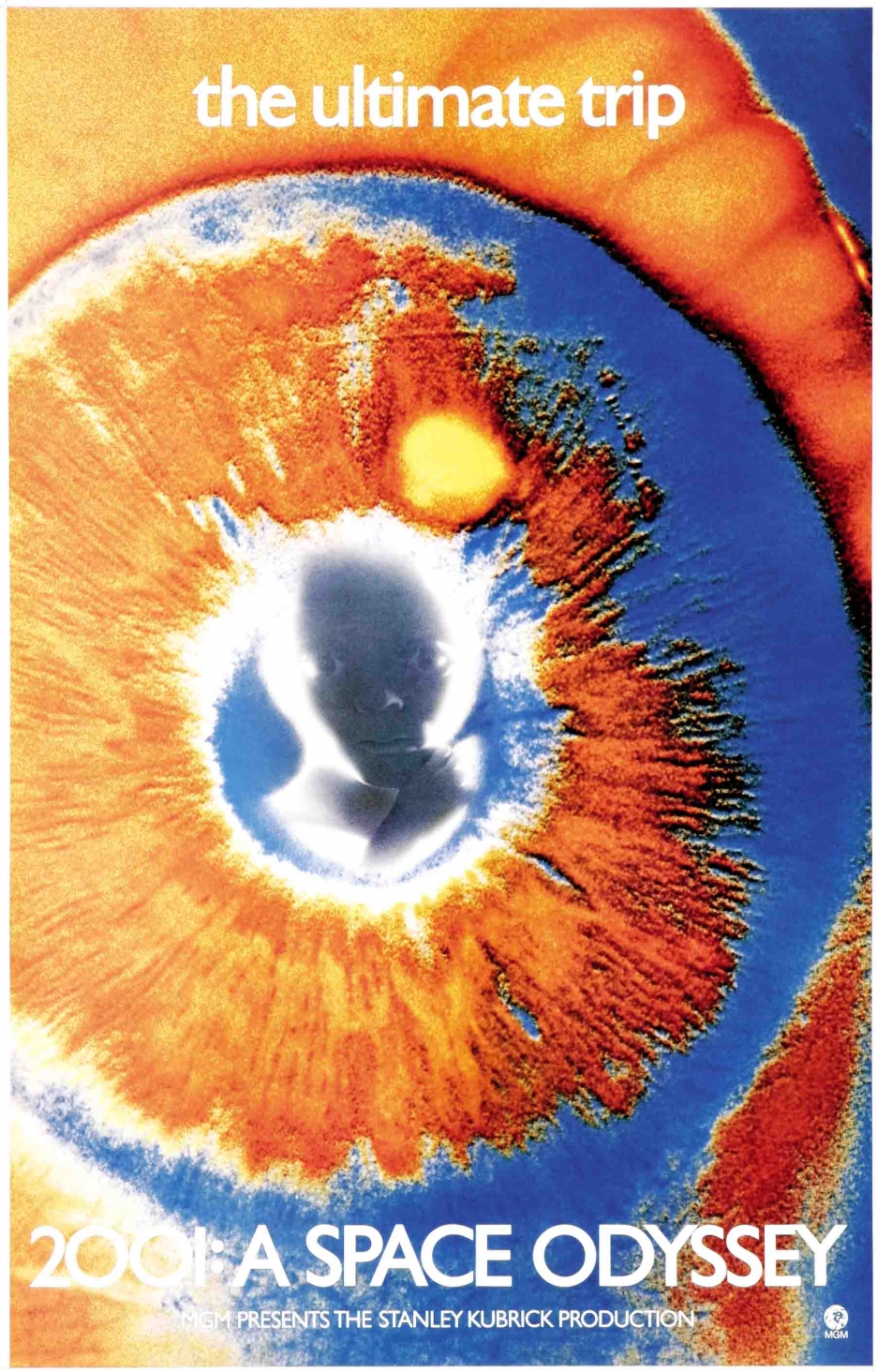

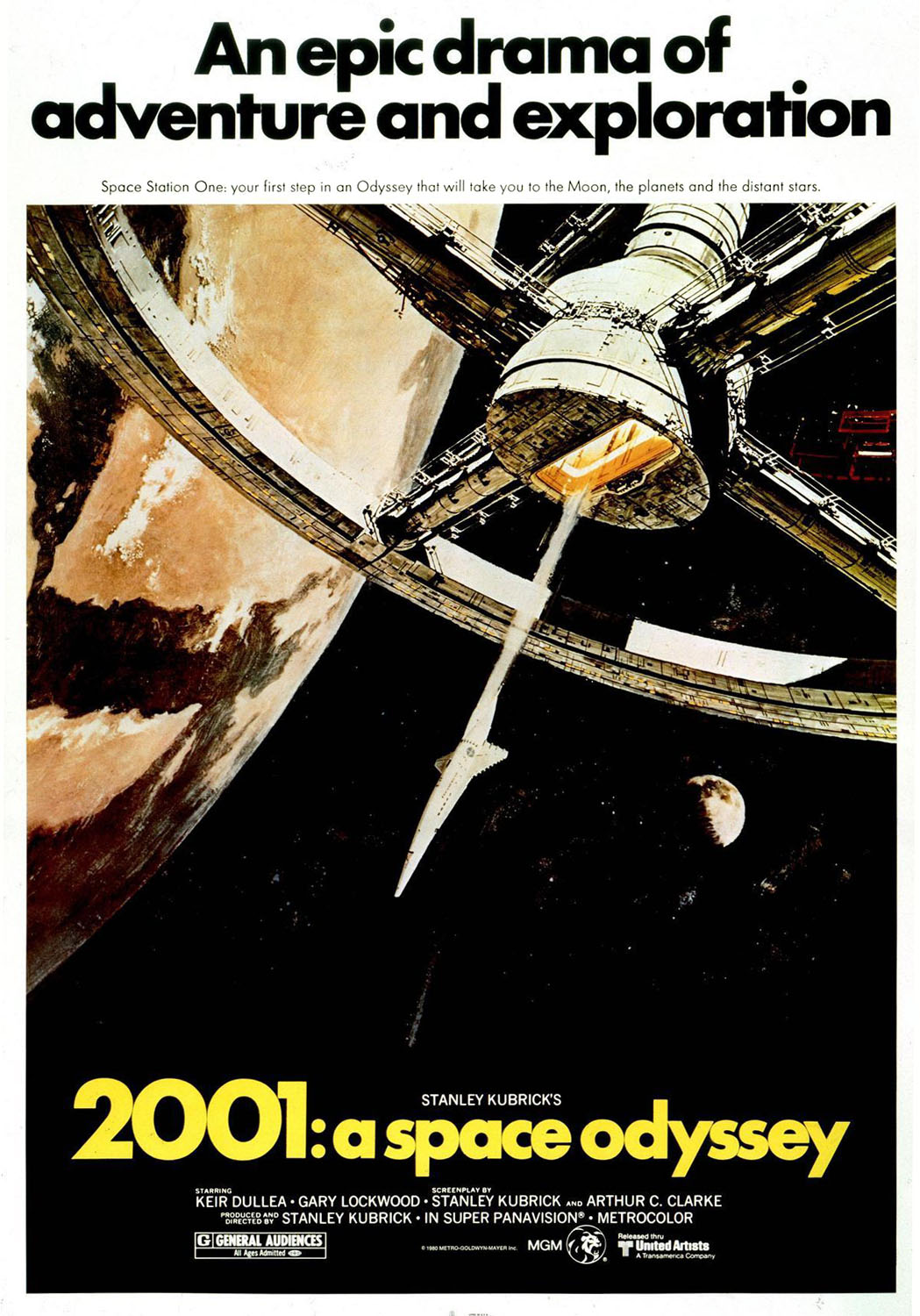

The diversity of admiring praise and sneering derision that we see in the quotes from famous people was likewise matched by the opinions of the general public, though after the film began to establish its audience of loyal supporters and repeat viewers, a notable skewing of the audience toward the younger and hallucinogenically-oriented end of the demographic spectrum was easily observed. MGM’s marketing scheme veered away from the more straightforward appeal of a futuristic quest modeled after the ancient epics of old (the “Odyssey” reference, obviously) and toward those who would be drawn in by an experience of “the ultimate trip.”

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

To get a very personal insight on how 2001: A Space Odyssey speaks to me today, I recommend that you give a listen to the full-length solo commentary track that I recorded on April 30, 2016. I went into my first ever solo podcasting session pretty directly, without a great deal of planning, just an impulse to watch the film on Blu-ray at home and speak into a microphone to capture my thoughts as they occurred. I’m satisfied with how it turned out, even though just focusing on the immediate business at hand as the movie plays out doesn’t always allow me to offer a more expansive take on some of the big ideas that Kubrick (and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke) raised in the film. I suppose that I could do so here in writing. I have this feeling of much that still remains unsaid, of inspirations I get from watching 2001 that I haven’t sufficiently expressed in this essay, though I’ve touched on quite a few of the topics that rev me up and put me in touch with that rare multi-sensory grandeur that fine cinema is uniquely capable of delivering.

Kubrick’s vast visual symphony truly does create a space for ecstatic personal introspection as we become more familiar with its cavernous contours, and his decision to dispense entirely with dialogue for long stretches of the movie was crucial. I’m sure he realized just how magnificent his carefully constructed images would be, and that too much human chatter would only serve to distract us from the vistas he would have us behold. The speculative elements of the cosmic story represent an intelligent, educated but ultimately fanciful guess as to where we came from and where we’re going. It’s best not to take all that too seriously, just as it’s absurd to find fault with Kubrick’s overestimation of how rapidly the space program would progress in its ability to put human bodies into extraterrestrial realms. What Kubrick and Clarke get right here is found in their ability to depict our existential solitude when the human journey reaches its ultimate limits, and the inevitable failures that we’re bound to experience when we rely too much on the tools that our ingenuity has designed to make the universe a little easier to control and a bit more convenient in meeting our needs.

I suppose that’s enough for now. Rewatching the film again this past week just adds one more chapter to a series of enthralling experiences that I’ve enjoyed at different stages of my life, beginning in my childhood, and accompanying me through the decades into my adult years. This current revisit of the film has only tightened the bond that I established with 2001: A Space Odyssey back in 1968, when my dad took our family to see it in Detroit in a theater equipped with the Cinerama screen. I was all of six years old. Years later I watched it on VHS as a young adult (pathetically butchered, I’m sure, but I was still awestruck), and with my kids on DVD in the 1990s as they squirmed in terror, their innocent young Nintendo-loving minds grasping for the first time the dreadful homicidal potentials that computers might unleash if their programming becomes too autonomous.

More recently, I’ve watched it on Blu-ray and in theatrical settings with friends, and alone in my home theater “just because,” well before it came up in my blogging queue. And now, I’m just glad that 2001: A Space Odyssey has a Criterion connection, as LaserDisc #60, released way back in 1988. It gave me the perfect excuse to immerse myself in this vision of Reality once again, and I’d love nothing more than for Criterion to get the rights back some day. And if the circumstances of my life allow me the opportunity to watch this epic drama, this ultimate trip one last time on my death bed, as I stare at the wide black screen, the monolith tipped on its side, I would consider myself a fortunate man to bring that lifelong relationship full circle. And of course I’ll be reaching out my hand and pointing at it when I do.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Criterion Collection essay by Howard Suber

- Video: Supplements from the Criterion Collection LaserDisc Edition

- LaserDisc Chronicles :: 2001: A Space Odyssey (YouTube)

- Palantir.net 2001: A Space Odyssey Internet Resource Archive

- A visual interpretation of 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Renata Adler (1968)

- Roger Ebert (1968)

- The Harvard Crimson (1968)

- Samuel R. Delany (1968)

- Margaret Stackhouse (1968 – Kubrick called her essay “perhaps the most intelligent I have read anywhere.”)

- Bright Lights Film Journal (2004)

Blogs / Podcasts

- A Sharper Focus (Norman Holland)

- Cinema Prism (detailed analysis and comparison of HAL and Frankenstein)

- Flixwise

- Ozu’s World (Dennis Schwarz)

- Rock N Reel Reviews

This is just a small sampling of many great essays and podcasts that have been composed on the subject of the film. Please feel free to recommend links to other worthy sources in the comments! I may add more here as I discover them.

Previously: Three Resurrected Drunkards

Next: Salesman

Out of fear of having the movie spoiled I stopped reading after the first paragraph, but I love how you mention that your “self directed study” has changed you as a viewer. Delving deeper and deeper into the treasures of classic and world cinema truly changes you as a viewer. A film that you once adored, prior to your complete descent into cinephilia, could now seem like a shallow representation of some masterpiece that went before.

I enjoy it much more when the opposite happens. You re-watch an old favorite, and appreciate it more than ever, seeing many layers and nuances that had been hidden before you submerged yourself in the language of cinematic storytelling.

Cannot help suggesting http://www.2001italia.it (disclaimer: it’s my blog!)