Much has been written about William Golding’s 1954 magnum opus “Lord of the Flies,” a book of extraordinary literary power whose true greatness is perhaps belittled by its ubiquitous place on nearly all high school English class syllabi. It is surprising then how little has been written about director Peter Brook’s 1963 film adaptation of Golding’s novel, possibly because it must always live in the shadow of such a literary masterpiece, though I consider it to be one of the best literary adaptations ever made. Both the source material and the film seem to exist like mirror images to me, unique in their media but existing as a single story literally refashioned from the page to the screen. When I first saw the film version of Lord of the Flies it was as if someone took the images from the book in my head and directly copied it on to celluloid as I envisioned it.

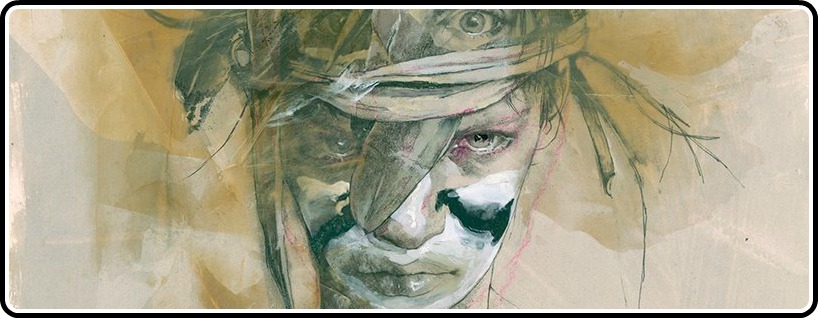

At a brisk 90 minutes the film is able to capture the raw savagery of Golding’s highly allegorical novel through a sly lens of absurd realism, establishing its black and white scenery with a free-range Nouvelle Vague-type technique as a way to forego any forced lyricism that a tropical locale would impose on the viewer. The film—like the book—presents a scathing view of the depths of humanity told through the story of adolescent British prep school boys stranded on a desert island after being evacuated during an unnamed military conflict. Brook, a renowned experimental theater director who had never directed a film before, sought to use child actors with no previous experience to populate the film. To him, children didn’t hit marks or try to construct their emotions in a role but rather if given the right circumstances would react with an unfiltered instinct needed for the story.

The performances are remarkably organic with the trio of core characters standing out. James Aubrey—who plays the mature pragmatist and elected chief, Ralph—brings with him the right amount of sincerity as the one boy who tries to preserve a sense of democratic order saying, “The rules are the only thing we’ve got.” His opposite is represented by the devilish Jack (Tom Chapin), who leads his fellow choir boys—later rebranded in a fascistic manner as “hunters”—to the brink by reverting back to an anarchic primitive existence, fashioning spears and donning warpaint with fellow hunters saying, “Bollocks to the rules,” and eventually forming a much more powerful rival tribe. In the middle of it all is Piggy (Hugh Edwards), the four-eyed outsider who embodies the malaise of the outcast with the authentic awkwardness of a truly troubled adolescent trying to cling to some sense of morality amongst the chaos.

The film’s symbolic dichotomies tend to define Brook’s vision filtered through Golding’s ideology. The image early on of uniformed boys marching in line down the shore of a tropical island portray Brook’s sense of the absurd, later defined as an indictment of the colonial British way of life as certain boys adhere to their casual politeness despite descending further and further away from a familiar civilized social system. Geoffrey Macnab’s essay that comes with the release asserts that Jack “looks like a younger version of those English protagonists found in countless imperial adventure stories,” and later points out that “with no natives to colonize, he bullies and rules over his classmates instead.” This cunning corruption of paradise—a miniature Fall of Man—forces us to pit purity versus primitivism in the most direct manner of questioning our own nature and whether we would also be capable of such behavior.

The release comes in a wonderful new restoration on DVD and Blu-ray that improves on the previous disc from 2000 with added special features, and makes for another great early spine number upgrade. The commentary with Brook, Producer Lewis Allen, Director of Photography Tom Hollyman, and editor/cameraman Gerald Feil is intact from the older release but offers the best look at anecdotal experiences in making the film. The most surprising thing is just how new everyone and everything was, and often times the entire production rested on Brook’s greenhorn assertions that what he was doing would work out in the harsh shooting conditions.

Brook’s methods are a bit out there as showcased by a new interview from 2008 and the inclusion of an excerpt from Feil’s 1975 documentary, The Empty Space, about a weeklong theatrical workshop put on by Brook’s International Centre of Theatre Research. The piece is filled with the type of clichéd exercises you’d imagine in an introductory theater course in college—including prolonged chanting and collective movement circles, and it also has a bonus young Helen Mirren cameo—but if it’s these types of hippie techniques that drew those performances out of the child actors in Lord of the Flies then something is obviously right. Another treat is the assortment of behind the scenes material including screen tests, outtakes, and footage shot by the young actors during production with a voice-over essay by actor Tom Gaman who played Simon. You get a sense of the small community of boys on summer holiday to make the film, and how they banded together in a similar way to the characters in the film.

Perhaps the best supplements on the disc feature Golding himself, a sullen, solitary figure who appears in an excerpt from an episode of The South Bank Show talking about how the story evolved out of the bitter class divide in his small English hometown through to his reaction to Victorian-era children’s swashbuckling literature and filtered by way of his personal experiences of the horrors of World War II. My favorite quote in the show is when Golding references Voltaire in describing “Lord of the Flies” as “A ‘Candide’ for the liberal optimism of the first half of the 20th century.” Golding also turns up in recordings of the writer reading from the novel played along with corresponding scenes from the film. The technique works in adding a poetic backdrop to the images, perfectly merging the two together that shows how they are both beneficially concurrent.

The film and the story itself are familiar but difficult narratives about the depths of human nature. It dares to ask how strong our social constructs are and whether an inherent savagery is found in us all. We may find solace in the fact that the boys are rescued in the end, but Macnab’s essay points to the inauspicious irony seeded in Golding and Brook’s vision – that though the boys may still revert back to the civilized society of their adult rescuers, “it was, of course, those adults and their bombs that put the children on the island in the first place.”