If Computer Chess seems like the kind of film that could only have been made on a dare, that might be because it was. Writer/director Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, Mutual Appreciation, Beeswax) had the elements of the film kicking around in his head for years – a gathering of tech obsessives in the pre-digital age, a desire to shoot on outmoded analog video cameras – but it was only in relaying these vague notions to a filmmaker friend over lunch, he says in an interview on this disc, that he found the proper motivation to execute it; his friend simply dared him to.

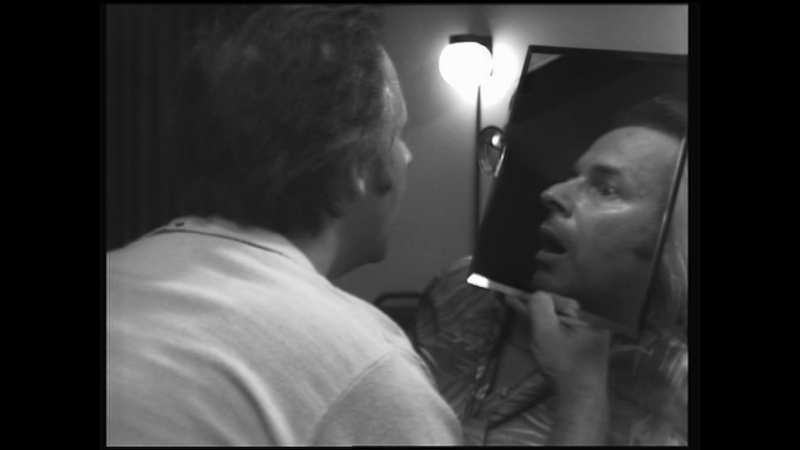

Indeed, it is hard to imagine a less commercial film. Bujalski is using the full frame, 4:3 format, black-and-white, deliberating creating only ugly images; he not only has no stars in his cast, but no recognizable names at all, and none of his newcomers are going to make the cover of magazines for their looks. The film is often discursively improvised, yet structurally rigid. It plays with notions of identity and artificial intelligence, the way pure developmental pursuits are corrupted by government and economic agents, and whether scientific study and spiritual movements can ultimately find the same nirvana. It also answers none of these questions, nor any else it might raise.

All of which – trust me, I know – makes it sound like a real slog. A more self-conscious filmmaker would probably be content to leave it at that. But Bujalski adds another layer, a nearly-documentarian look at the people drawn to such endeavors that is at once stiflingly awkward and ceaselessly hilarious. There is an extent to which he is engaging in the sort of freak show format that something like The Big Bang Theory gets so routinely lambasted for, but the thing that makes it work is that it’s part of an entire worldview in which all of his subjects, no matter how socially well-adjusted, appear ridiculous. As indicated above, his chief subjects – the computer chess teams – are contrasted with a sort of New Age-y (I know that term is hopelessly reductive, but at the same time, it’s all too useful) spiritual movement that’s also meeting at the hotel. Both are after the same transcendence, a very noble goal, and Bujalski isn’t necessarily mocking them for seeking it, but more standing bemused at the way our inevitable humanness – momentary desires and fears, distractions and complications – get in the way of such lofty ideals.

As mentioned above, the movie was shot on analog video cameras contemporary to the era Bujalski is depicting, retrofitted to record onto an HD format but nevertheless very much saddled with the limitations of their time. This is not only completely charming, but beautifully reflects the way the film’s subjects are reaching for something beyond their present technological means, forever inhibited and yet always pressing onward. I will say that the process makes it somewhat difficult to make any sort of traditional assessment of the quality of the image present on the new (REGION FREE!!) Blu-ray from Masters of Cinema, other than to say it looks like the DCP I saw in theaters, so I trust they’re handling their stuff correctly.

MoC has gone all-out with the supplements, providing two commentaries; a short film; interviews with Bujalski, actor Wiley Wiggins, and producer Alex Lipschultz; promo videos for the Kickstarter campaign, London Film Festival, and Sundance Film Festival; a series of videos highlighting the old personal computers used in the movie; two trailers; and a short featurette in which cinematographer Matthias Grunsky explains the inner workings of the camera they used to shoot the film. It’s a lot to get through, and not all of it is exactly necessary (of the promos, I’d say look at the Kickstarter one and call it a day; one commentary track features an unnamed “enthusiastic stoner,” and your own enthusiasm mileage may vary), but certainly the three interviews and first commentary track, conducted by Murray Campbell, one of the programmers behind the Deep Blue machine that was the first to beat a world champion chess player. It’s a great angle to take with a commentary track, as Campbell reflects on the ways in which the film’s depiction of the era is both dead on and slightly exaggerated, and proves a valuable supplement.

The included booklet is a little slimmer than we’re used to from MoC, with only an essay by Craig Keller providing a real meaty entry, but it’s a good one, and there’s plenty on the disc to do the heavy lifting, should you require it.

I’m of two minds on Computer Chess. Part of me struggled to connect with it while watching it and found some of the characters to be too dull to follow. Even so, I admire what Bujalski is doing and think it’s brilliant in a certain way. I may not run back to check it out, but I’m glad it exists.