I first saw if…. around the time Criterion released their initial DVD edition back in 2007. Having been enamored with Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange for several years prior (Kubrick’s New Hollywood burst of anger and sexuality jives quite well with a young man in his late teens), I was intrigued by this film that apparently introduced the master filmmaker to one of his defining stars. I found it wholly dismissible. So now I sit down to watch it, some seven years later, a wholly different person who nonetheless likes to think he’s retained some of his rebellious nature from those years. For what little value the real estate of my mind has, I will nevertheless say that the damn thing has scarcely left since it re-entered a few weeks back.

Anarchy is appealing, I’ve found, regardless of political persuasion. Nearly any system will be wholly objectionable to the vast majority of those it governs. Leaders are as reflexively despicable as they are charismatically electable. Plus, Anderson paints them to be such insufferable stuffed shirts. if…. was shot in March and April of 1968; one month before the landmark protests in France, and the same month Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed. It hit British theaters that December, and the Cannes Film Festival the following year. Hell, there’s a whole Wikipedia entry just on the protests around the world from that year. Telling the story of a group of students who plot and eventually stage (or not) a violent revolution at their boarding school, if…. could not have been more of the moment.

Yet it is not tied to this time, and owes only the texture to its place. In the nearly fifty years that have passed since its release, the System has managed to accept the fashions of the young and frustrated, knowing that will at least placate the potential of meaningful revolt. Yet young people are still furious; they just have fewer modes of expression. We have been taught that protest is ineffective, that corruption is inevitable, that alternative styles are laughable, that unemployment may be rampant but if we keep our heads down and out of trouble, we’ll be all right. Something within us simmers, unable to explode because our debts are too high and our fashions inadequate. if…. is still about that potential revolution, that yearning to tear it all down. We’re also taught that no system is worth destroying without a viable alternative. In if…., there are no such concerns. Any system would be preferable. Even no system at all.

The tension that drives the film is not that which nearly any other filmmaker would rely on. Given the story set-up, it would be natural to assume we’d be left constantly guessing and wondering about the eventual actions of the students and their opposition. How far would each push the other, and what would it all come to? if….‘s tension is ideological. How boldly can the students dream, and how much can their administrators suppress such fantasies? The film contains many fantastical sequences, but which ones, and to what extent? One might easily assume that the brief shot of Malcolm McDowell and Christine Noonan rolling about the floor nude is an esoteric exaggeration of their animalistic flirtation, but that’s assuming quite a lot already (for example, if the flirtation itself happened at all). The film is not the surrealistic voyage of late-period Fellini, and yet there is something unreal afoot, climaxing in a battle scene that simply couldn’t happen, and perhaps doesn’t. Whether any of it is “real” matters not; the emotions are real. The thoughts are tangible. The yearning and oppression almost suffocating.

This was McDowell’s first film role, and it’s little wonder that it was his springboard into everything he would do afterward. He isn’t just sly and charismatic; he suggests in every scene that his blase attitude is a coping mechanism for a well of resentment and despair. “When do we live?” he asks, “That’s what I want to know.” He tries, by growing a mustache over the summer vacation or stealing a motorcycle or pulling a plastic bag over his head or gradually wearing down a bottle of vodka. Eventually, such measures won’t be enough.

I guess there are those for whom it might be worth clarifying that the film is not a call to violence, but an expression of that call. There is a difference between condoning violence and understanding it. Given the word we live in, understanding it might be to our greater benefit.

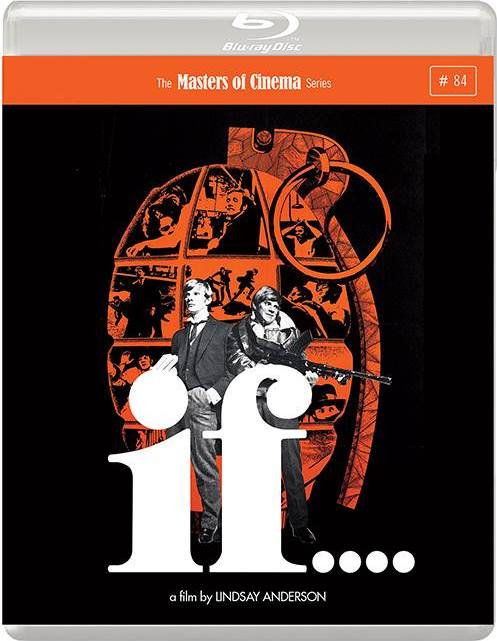

if…. looks very nice in high definition, courtesy of Masters of Cinema’s new (Region B locked) Blu-ray edition. I don’t have the Criterion Blu-ray at hand, but from what I’ve read, the transfer is virtually identical. Both the color and black-and-white sequences are very nicely handled, the latter favoring gray over heavy contrast, which lends a sort of dreamlike, erotic quality to the whole thing, as though nothing is too well-defined. The colors are purposefully natural and suitably replicated as such. Grain is light, but noticeable and beautifully textured. It’s relatively free from damage, and quite nicely cleaned.

The special features, however, distinguish it tremendously from Criterion’s edition. Both share the same very good commentary track by film historian David Robinson, with occasional input, via an older interview, from Malcolm McDowell. The balance between the two voices – one studious, the other professional – give a very fine overview of the film’s power and legacy.

From there, MoC provides not one, not two, but eleven cast and crew interviews, ranging in length from 3 minutes (camera operator Brian Harris) to 47 (actor David Wood, who plays McDowell’s best friend), with most of the others falling under 10. Not all, naturally, are of tremendous interest, but the vast majority are, and the piece with Wood in particular is a fascinating look into Anderson’s process.

MoC further sets itself apart by providing three short films by Anderson – Three Installations, an industrial film; Thursday’s Children (also available on the Criterion), a documentary on a school for deaf children (which won the Oscar for Best Documentary, Short Subject in 1955); and Henry, a short promotional for the children’s welfare agency NSPCC. All are presented in high definition, with the first two looking considerably better than the last. I always appreciate when MoC or Criterion includes early shorts by the director of the film they’re presenting, which has lead to some fantastic discoveries (Resnais’s Toute la mémoire du monde has long remained a highlight), and Three Installations in particular really stood out here. From there, there’s the usually exceedingly well-done booklet, this with two essays by David Cairns, and interview with actor Brian Pettifer, Lindsay Anderson’s interview with himself (a fashionable bit of publicity in the 1960s), and three short essays by Peter Hoskin and Ros Cranston on the short films.

It is altogether a tremendous package, one I was especially pleased to dive into after finding the masterpiece about which I’d heard so much all these years.

This is a tremendous piece, Scott, in analyzing the spirit and identifying the content. A very good piece of writing too. This and many others from the British New Wave have inspired me very much. Tons of emotion and technique. An underappreciated period, in my opinion. Keep up the great work.