Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, based on a 13th-century Swedish folk ballad centered on rape, murder, and revenge, is one of the few films Bergman directed but didn’t write the screenplay for (that credit goes to Ulla Isaksson). Nevertheless, the film is concerned with questions of faith and silence in a world of chaos, themes Bergman was exploring throughout this period of work. The film shows that beautiful days can turn horrific, even for those who pray for better from God, even for an innocent. Is this due to God’s punishment? Is it a trial meant to cleanse and deepen faith? Is it just chance? All of those can be terrifying possibilities.

This film takes us back into the brutalities of the medieval world Bergman and his star, Max von Sydow, dwelled within in The Seventh Seal. Here von Sydow plays Tore, the proud father of the beautiful, young, tragic Karin, played by Birgitta Pettersson.

The story is simple. The day begins beautifully. The family, a well-to-do Christian family, goes about the business of waking up and preparing for the day. Karin, because she is a virgin, is tasked with delivering candles to the church. When she wakes up, late, Tore plans to chide her a bit; he wants to be more stern, but she always disarms him, charming him with her exuberance for life and her naive belief in her own infallibility.

Despite Karin’s naivety and prancing, she is presented as an honest, admirable, caring young woman. We see why that Tore loves her for the person she is as well as for being his daughter. Karin’s mother, Märeta (Birgitta Valberg), loves her dearly as well and is jealous of the fact that Karin’s favorite parent is her father.

One person who does not admire Karin is Ingeri (played by Gunnel Lindblom), a young woman the family has taken in. Ingeri is actually the first person we meet in the film. She’s disheveled and, we soon see, pregnant. As the story develops, we see that Ingeri is jealous of Karin and disgusted by how everyone thinks Karin is essentially an angel. Karin doesn’t believe in angels. In fact has prayed to Odin that something wicked would happen to Karin.

Ingeri is the one who is to accompany Karin on her journey to the church.

It’s a gorgeous journey in crisp sunlight, rendered even more stunning in The Criterion Collections new Blu-ray edition, where the light reflects and the film sparkles.

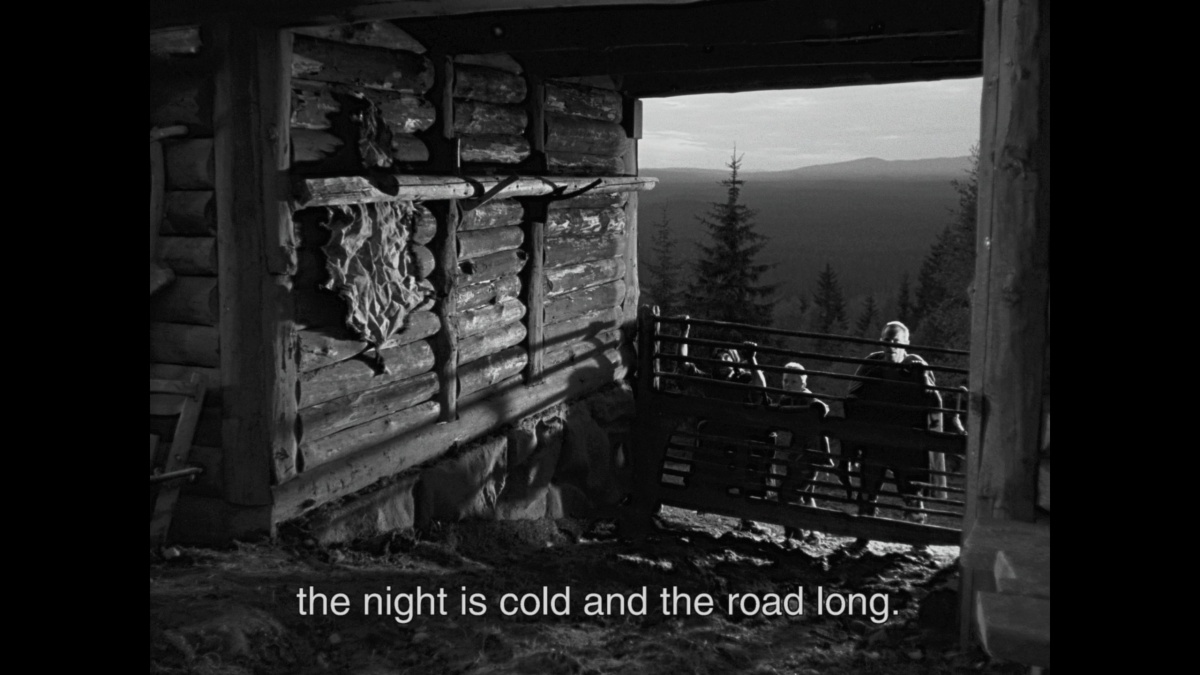

Nevertheless, as they make their way to the church, the growing certainty that something bad will happen puts Ingeri on edge. After a horrifying encounter with a fellow pagan —

— Ingeri is separated from Karin, who falls in with some ill-willed herdsmen.

You know what happens. It’s fairly early in the film, so I don’t think it’s a spoiler to be so specific here. The power of The Virgin Spring is in the fallout. How will her parents react to the horror, knowing their prayers were not answered and their innocent daughter was brutally taken from them? How will Ingeri respond knowing her prayers were answered?

It’s a powerful film about grief and the desire for revenge, and it only increases in intensity when Karin’s parents allow Karin’s murderers to stay with them for the night. They learn of her fate and plot their own imperfect and unsatisfying revenge, contrary to their own Christian faith.

The Virgin Spring also marks the beginning of a long-lasting film collaboration between Bergman and legendary cinematography Sven Nykvist. They had worked together before, but it was limited. When Bergman’s regular cinematographer, Gunnar Fischer (whose work is wonderful as well), was unavailable, Bergman got Nykvist’s services. From that point on, Nikvist’s powerful vision influenced the pictures Bergman would make as he explored religion, faith, and existential dread.

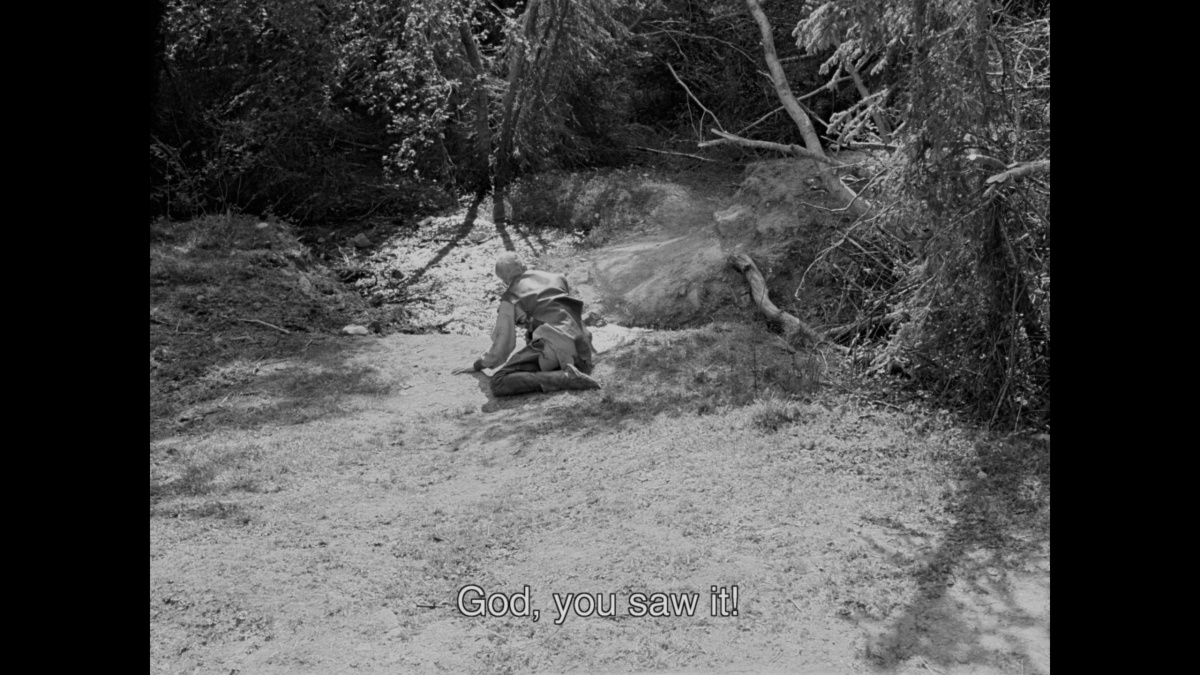

Those themes come front and center here, as well. An innocent child is murdered, and her father cannot understand how it could have happened because, as he says, “God, you saw it!”

Besides the quotation, I think the shot above is thematically significant and wonderfully constructed. Tore is looking up into the light, speaking to God. Often directors shooting similar scenes will position the camera above Tore and angle it down toward his face, as if God is the camera, watching and listening. Even when the subject is angry with God, that would be the conventional camera position. Shouldn’t we see the anger on the subject’s face, after all?

Here, though, Bergman puts the camera behind Tore, and Tore is so far in the background, it’s not clear he’s even the frame’s subject. This suggests a couple of things to me: Bergman is saying that Tore is looking at nothing, and nothing is looking down on him. Then again, the camera is raised, so, if we are looking down on Tore from God’s perspective, then yes, God saw what happened, but only in the periphery. In either interpretation, Tore’s anguished prayer is pushed out of the foreground, as if it’s really rather meaningless.

It isn’t meaningless for Bergman, though, nor for us. This is torment, that moment when one’s faith is shaken, when one witnesses chance, arbitrariness, an irreparable end. The film does conclusion with a kind of miracle, slightly subverting this doubting camera angle, but this struggle with faith will not go away for Bergman, and his exploration of these struggles has been the highlight many of his best films.

![Virgin Spring [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/412nuMu3cmL._SS520_.jpg)