Young Mr. Lincoln is certainly not John Ford’s most famous film, most respected film, or most important film — heck, it’s likely none of those things even in 1939 because that year Ford also release the landmark film Stagecoach. Beyond that, if you’re watching Young Mr. Lincoln in an uncharitable mood the film will probably come of as cloying, sentimental, nostalgic for a time that never existed. From a broad perspective, it can definitely feel saccharine and simplistic, with villains stirring up gullible townsfolk to prosecute to the death the meek sons of a wronged, earnest family with nothing but holiness and a desire to work in their hearts. Who can right this wrong? The young Mr. Lincoln, who, early in the film, is struck by a deep truth while studying the law: “By jing, that’s all there is to it. Right and wrong.”

But despite these aspects, the film is magic. I won’t even call the above weaknesses because it turns out Young Mr. Lincoln is a film that isn’t all that concerned with having a complicated plot or complicated side characters. It’s not even concerned with history; everything historical that happens has only the slightest link to some fact cherry-picked from Lincoln’s life (and not always from his youth). All of that is incidental. Rather, the film is concerned with our perception of a man we’ve set apart from the rest of his time in our history books, a man who is bigger than his life. It is concerned primarily with imagery and, as such, it is a masterpiece. To me, among many remarkable films with iconic imagery (scenes from Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, and The Searchers spring immediately to mind), Young Mr. Lincoln is John Ford’s most perfectly composed film, which suits its subject perfectly.

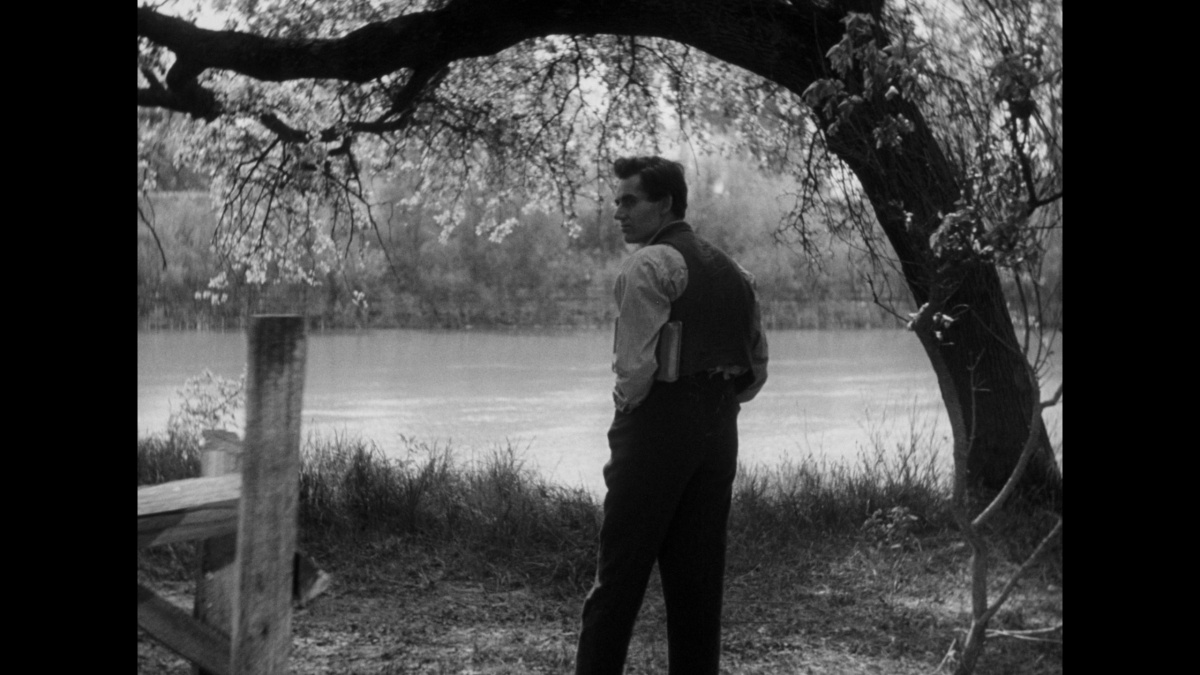

In a film that can appear relatively simplistic, John Ford keeps Henry Fonda’s Lincoln as an enigma, a man both right in the middle of things and a man who stands apart. We first meet Lincoln when he’s still a bit of an oustider in Springfield, Illinois. He’s young and hasn’t even started studying law yet. He’s in love with Ann Rutledge (a relationship that is not historically established), and for the most part he’s trying to find a place. His youth looks idyllic, with the heavy river flowing onward, a near constant reminder of Lincoln’s ultimate destiny.

This last image of Lincoln with Mary Todd is a good example of how Ford also shows Lincoln facing something different than the men and women around him.

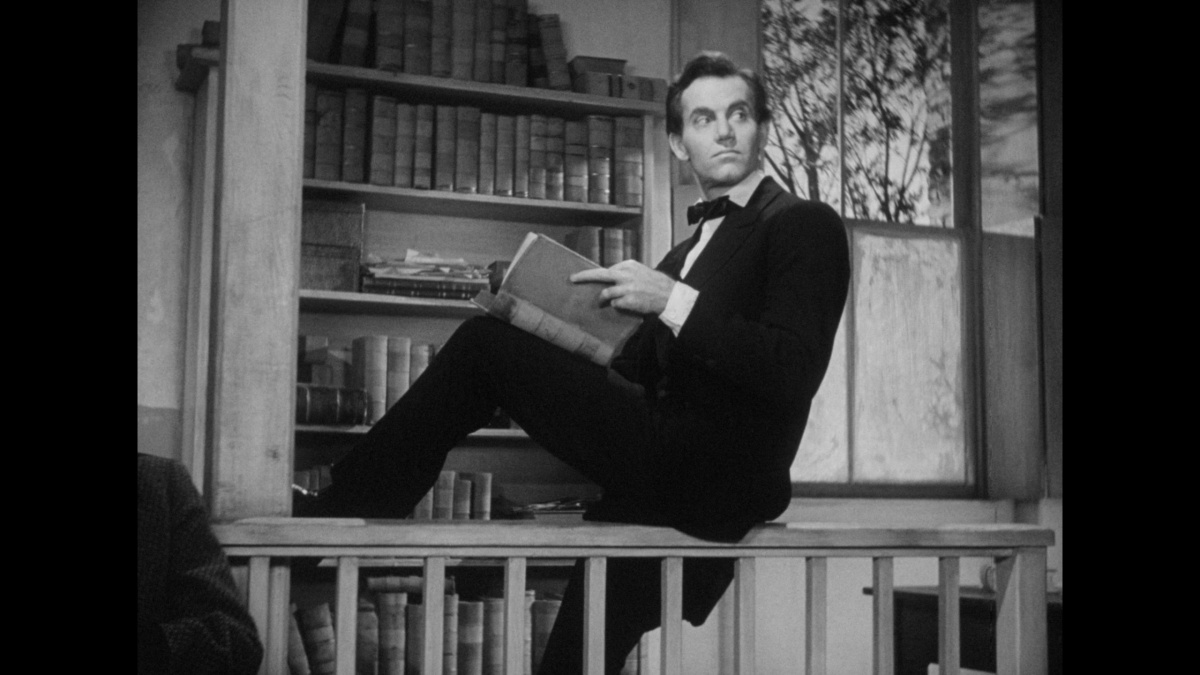

Interestingly, Ford also shows Lincoln as a man at ease, which is a strange counter to the lofty images above where Lincoln stands nobly. But look: there are multiple shots of Henry Fonda lounging. In this shot below, we look in on Lincoln’s first days as a practicing attorney. He seems alone in the room. We hear a couple of men arguing at each other, while Lincoln relaxes.

We might expect the bickering men are outside Lincoln’s office, but no: this shot soon opens and we see that the wall and door were blocking our view of them. They stand on either side of the calm Lincoln, arguing around him.

Even when in the midst of defending the two young men in a murder trial, we see Lincoln relaxing (and it’s nice look into the future when we see Fonda playing Wyatt Earp for Ford in a similarly relaxed manner amidst all of the hub-bub).

In the next screencap, we see Lincoln reading a book while the trial goes on.

We may meet him as a humble newcomer, but Lincoln soon transcends the town, and by the imagery we see that Ford is portraying him as transcending much more. He is a wise steward, here to calmly assist temporarily before he moves on to another plane entirely.

The weighty images work perfectly with the images of Lincoln at ease. In our podcast on the episode, David Blakeslee likened Fonda’s Lincoln to a zen master, and I think that’s an apt description, one that takes into account Fonda’s physical portrayal of Lincoln with Ford’s images of the river and the storm that eventually shows on the horizon.

This really is a special movie, and one I can rewatch frequently. I admit that even though I see the simple tale as some idealistic portrayal of a world that never has been, I don’t care at all about that. I’m here for Ford’s visual poetry and Fonda’s earnest calm, each of which pay tribute to a man we really cannot understand but whose myth is worth pondering.