In his initial review of Midnight Cowboy, Roger Ebert decried the film for being gimmicky; he saw greatness in it but was frustrated, saying that it was “like looking at a great painting through six inches of Jell-O.” In particular, Ebert accused Schlesinger of pushing too much style, adopting too many of the then-vogue techniques, obscuring the truly deep and touching story at its center. Ebert, like many of his contemporaries (Vincent Canby, Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris), felt that the film wouldn’t survive.

The film is about to turn fifty years old and was recently released on home video again by The Criterion Collection in a loaded package. Despite the doubts, the film has lived on. Sure, some of this is because it won the Academy Award for Best Picture and has gone down in Oscar history as being the first and only X-rated film to do so (that’s certainly why I first heard of it when I was a kid playing Trivial Pursuit), but I don’t think that notoriety is the only reason this film is still around. While I may agree with some of Ebert’s criticism (which he stuck to when he re-reviewed the film 25 years after his initial review), I think that the central story of Midnight Cowboy, about two men trying to make it through each day, adopting roles they were never meant to perform, transcends any of the film’s flaws. Their story sticks. I first saw it a couple of decades ago, and it affected me deeply. After rewatching it this past week, I am even more impressed that the film still talks to our hearts today, in world that is quite different from the one in the film. Why? We still experience shame from our past and the desperate hopes and dreams in the face of an uncertain future, and we can still recognize the anguish of others who are beaten down by all of this.

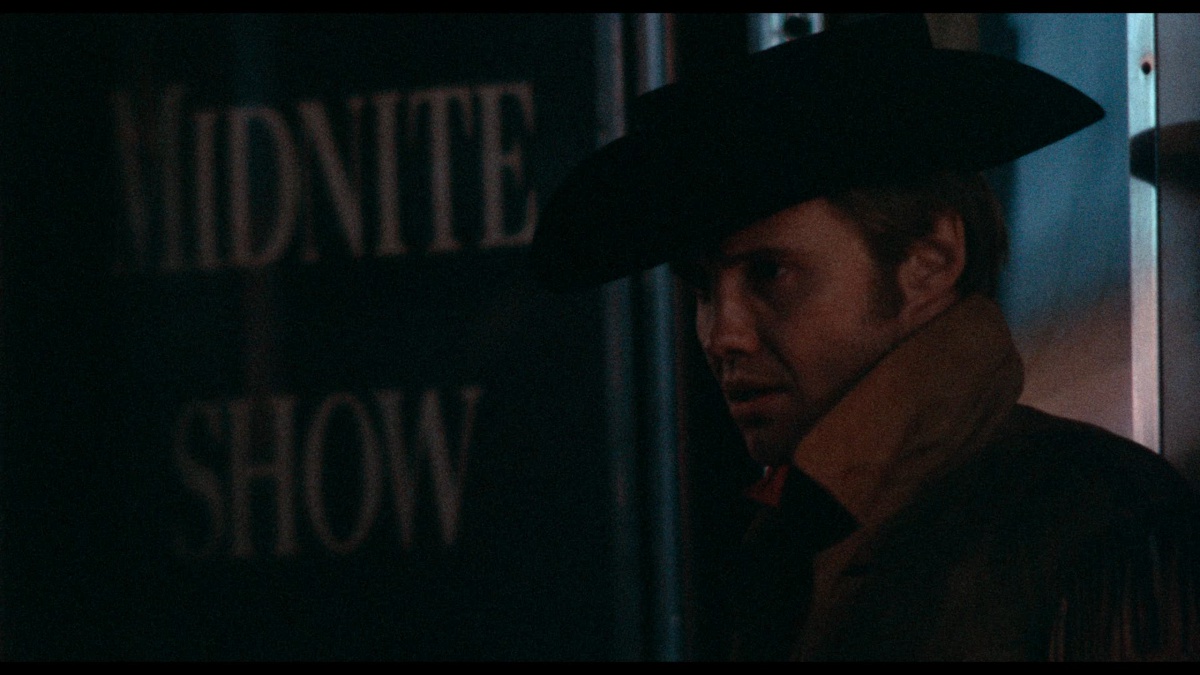

Jon Voight plays Joe Buck, a Texas boy with good manners. We meet him as he dons a new cowboy costume he purchased with money he earned washing dishes at a diner (he’s no real cowboy) and trying on the role and speech of a confident, even cocky, stud.

This is who he wants to be. He’s delighted by the sight of himself and looks at the camera to say something he wouldn’t say to anyone actually in the room:

You know what you can do with them dishes. And if you’re not man enough to do it for yourself, I’d be happy to oblige. I really would.

Voight delivers these lines perfectly. Much like when Travis Bickle performs for the mirror in Taxi Driver, we know this identity is like a new outfit, and in this case the performance comes from a well of insecurity.

Joe’s preparing for a new life. He’s quitting his job and packing up to seek richer streets in New York City. As he travels by bus to the big city, we see him thinking back on his life in Texas in disjointed flashbacks and see a man trying to escape a past as well as an identity that filled him with shame.

In New York, Joe plans on being a male prostitute (which is one of the reasons the film was rated X, though it was re-rated R a few years later, with no cuts). He thinks that his cowboy get-up and his good looks will really please those wealthy New York City women and will help him pull in easy money.

He’s no good at his job, though. For one thing, he’s not original. There are several other cowboys standing against the grimy buildings. In the rare instance when he does get invited to a room, he is taken advantage of. Here he is giving one of the women (Sylvia Miles, who got an Oscar nomination for her performance in Midnight Cowboy) $20 after she yells at him:

You were gonna ask me for money? Who the hell do you think you’re dealing with, some slut on 42nd Street? In case you didn’t happen to notice it, ya big Texas longhorn bull, I’m one helluva gorgeous chick.

It’s at this early desperate time that he first meets Dustin Hoffman’s Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo, a penny-rate conman who at first eyes only Joe’s wallet.

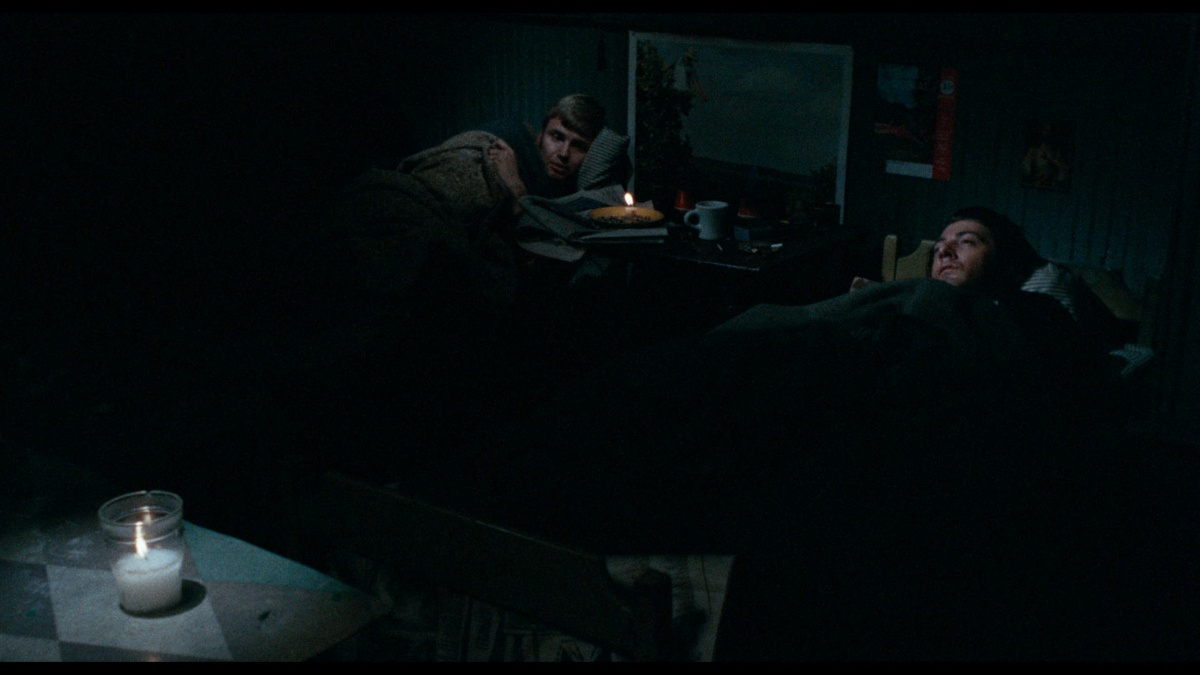

Ratso says he can be Joe’s manager, help him play the game for a cut. For Ratso, Joe may be a ticket out of New York. He’s crippled and probably tubercular, and he’s right when he thinks he cannot survive another New York City winter essentially homeless.

And so Ratso dares to dream:

But the reality is so far removed from this dream. The dream is an impossibility. For one thing, Ratso can run in the dream. For another, the warmth of Florida is nothing like the chill in their shared room in a condemned building.

Theirs is an unlikely friendship, but nevertheless a friendship does grow here, perhaps the most significant friendship or relationship either man has ever had. That’s not to say it’s particularly healthy. Each man is injured in some way and feels compelled to put up a front of impervious manhood. To do this they attack each other, trying to assert their independence and even superiority with slurs and digs at the other’s abilities with women. Still, these moments brake down and we see they eventually come to depend on the other. It is a touching friendship, all the more so because their vulnerabilities are so clearly rendered by Voight and Hoffman, both nominated for Best Actor the year John Wayne (a model for Joe’s cowboy perfection) for playing Rooster Cogburn in True Grit.

It’s this relationship that carries the film and makes it soar despite some flaws that are commonly pointed out, the two primary ones being some flimsy flashbacks and an unlikely Andy Warhol-esque party, each with stylistic flourishes that go against the grimy realism of the film’s strongest moments. The party sequence is an unnecessary relic of its time; I’m sure that when it started in his theater in 1969 Ebert threw up his hands, wondering how often he’d be subjected to these psychedelic interludes. And though the flashback scenes give us a sense of the source of Joe’s shame, I think they’re unnecessary too. We can get all of that from the central story. At worst, these flashbacks derail otherwise poignant scenes, like one involving a very young Bob Balaban. Still, these flaws don’t ruin the film for me.

Now, on to more of the strengths. I want to turn to the tormented, titular midnight cowboy at the center, a man who left Texas, I don’t believe, because he thought being a male prostitute would make him a lot of money. That idea, too, I feel, is a front. Joe Buck himself is unwilling to acknowledge it, but I get the sense that one of the primary reasons he leaves Texas and even chooses a job he thinks will please women is to assert his unhealthy notion of masculinity and to hide his shame at his own homosexuality. While Joe’s homosexuality is never spelled out explicitly (the homosexual perspective is the primary reason this was X-rated), likely this is because he’s hiding it from himself as well. It’s a side of him that he despises and chooses to ignore and even deride.

Indeed, the film’s characters deride homosexuality throughout. When we first meet Ratso, he’s using slurs to ward off a gay man who is trying to warn Joe that Ratso is a crook. Ratso often says that Joe’s cowboy outfit is only meant to appeal to the gay men lurking on 42nd Street. Joe, for his part, responds to all of these with anger that rather uncovers a vulnerability in his defensive front. This is the anger that allows him to perform when a woman he’s with questions his sexuality. This is the anger that pushes him to beat a kindly but shame-filled married man who, I think, he recognizes in himself. This beating is actually a part of the film Ebert questions, saying he doesn’t see it as truthful to Joe Buck’s character. I see it quite the opposite, feeling it reveals the man Joe Buck is trying to suppress. Joe Buck’s first lines in the film are him singing this: “Get along little doggies. It’s your misfortune and none of my own.” This is followed by, “Where is that Joe Buck?”

So what does the future hold for a man so confused about the role he plays in his own life, a role molded by a painful past of abandonment and religious terror, a role molded by vicious masculine role models, a role he lets slip slightly when he cares for his friend Ratso? We don’t know. It’s something I’ve wondered a lot over the years since I first saw the film. I think that unanswered question is yet another reason the film has stuck around and will continue to for years to come.

![Midnight Cowboy (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51c+pTaRxgL._SS520_.jpg)