In the early 1990s, producers of a planned television series called Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge (All the Boys and Girls of Their Age) contacted Olivier Assayas and eight other directors and asked them each to make an hour-long film about their own teenage years. The series didn’t quite work out as planned, but one of its fruits is Assayas’s contribution, Cold Water. Determined to use the tiny budget to create a short feature of 90 minutes instead, Assayas shot the film on 16mm over the course of a few weeks and then, along with others involved, realized something special had been created.

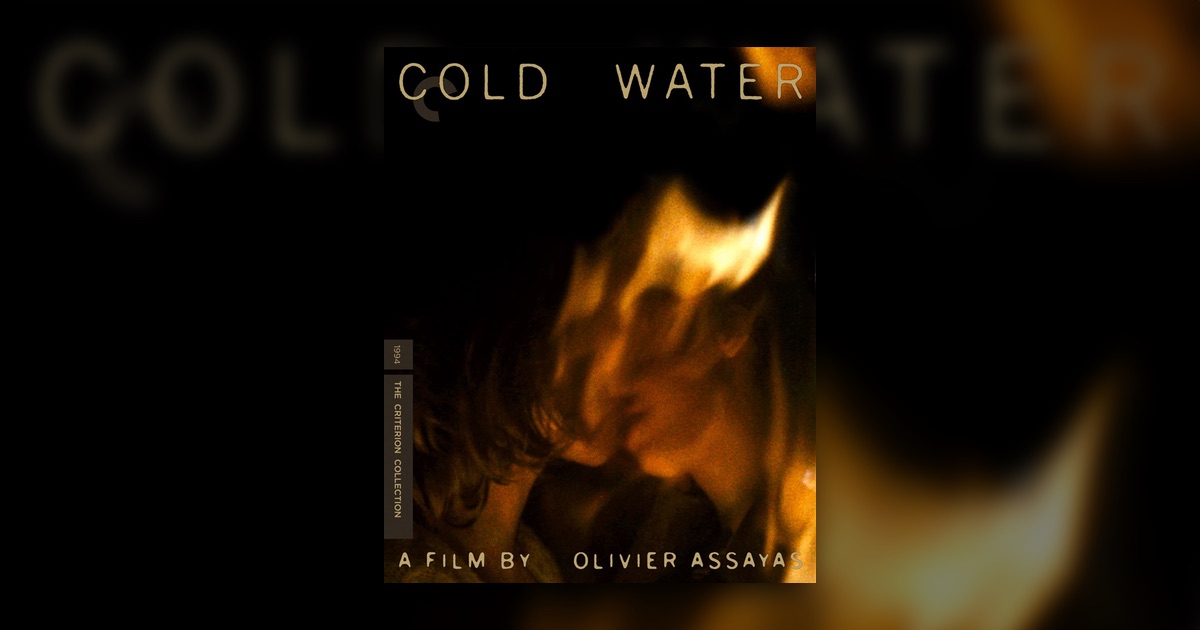

The film went on to screen at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival. However, since then, the film has been hard to see, particularly in the United States where expensive music rights essentially made the film unavailable. Thanks to dedicated work negotiating those rights and then restoring the film, Cold Water is now out there for anyone to see in a new home video release from The Criterion Collection. This is how it should be. The film is a wonder as it explores youth in the Paris suburbs of the early 1970s.

When the film opens, we meet the two central characters, Gilles (Cypprien Fouquet) and Christine (Virginie Ledoyen). They’re hanging out at a record store. They chat a bit, but the contents of their conversation don’t matter nearly as much as the non-verbal signs of connection. Gilles watches Christine with attention, and she smiles.

Eventually she turns to him and reaches out, and he smiles too.

These could be any teenagers, anywhere, but the special connection they have underscores their importance as individuals, both to each other and to us.

Before we know it, though, Gilles sticks a bunch of records in his bag and they attempt to flee. Gilles escapes, but Christine is taken into custody. This, we come to understand, is nothing new. They’ve each been here before. Gilles’s father is frustrated, though he tries to provide a nice home. Christine’s father, on the other hand, has had it and sends Christine to a mental institution.

While we don’t really get a chance to know a lot about Gilles and Christine, we learn enough. Do they know each other? Do they fully comprehend what the other is going through? Probably not. They are both frustrated and seeking to lash out, but they’re anger comes from different places. Still, it’s enough that they’ve experienced that connection and know it comes from genuine compassion.

It’s not a surprise, then, that when Christine finds a way out of the institution she seeks out Gilles instead of her father or mother. It’s not really a surprise that the place they’re able to meet up is an abandoned manor far out in the countryside where kids from all over can come to listen to rock and roll, light up, and forget the world for a night.

What is surprising is how beautiful it all is. These are troubled kids, yes. They’re doing things kids shouldn’t do. But their momentary reprieve is conveyed so well I cannot help but hope they fully escape, even for just one night.

This strangely vibrant yet serene party sequence is the most notable portion of this film, and it goes on for nearly a third of the run-time. In it, Assayas’s hand-held camera flits around the room, giving us quick pans, extreme close-ups, and shaky imagery. In some films this approach can feel fake and self-conscious, but in Cold Water it perfectly encapsulates the world for these teens. It’s relatively small. When they look at each other, they are focused, even if the vision is shaky and fleeting.

It’s beautiful. And the many teens who get the attention of the camera, particularly the magnetic Christine, who is not having an easy night and yet who still manages to stop your heart when Gilles finally finds her, are beautiful.

There’s nothing to indicate Gilles and Christine have much in common or that any long-term relationship would work. But in this turbulent time, it’s enough to know that someone, even someone with problems, cares and doesn’t judge, even if the morning is inevitable.