Early in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1975 film Fox and His Friends, the naive protagonist Franz Biberkopf (played by Fassbinder himself) shows he’s not quite as naive or, at least, not quite as innocent as we may be led to believe through the remainder of the film. Biberkopf, who goes by the nickname Fox, plays the lottery as if it’s some religious ritual, filled with hope and faith that his fortunes will change quickly when change sees it’s fit to come his way. Fretful because he doesn’t have the money to purchase his ticket, Fox carries out a swindle so naturally that he’s surely done it before. Or perhaps Fassbinder is saying this is natural because this is just how humans behave. In either case, Fox enters a flower shop, flirts lightly with the gay florist in order to gain trust and instill desire, and then slips away with some petty cash. Meanwhile, waiting in the car is Fox’s brand new friend, Max (Peeping Tom‘s Karlheinz Böhm). Max is an upper class man who just picked up Fox at a rest stop a few miles back because he enjoys the periodic fling with a working class man, and the young, uncultured Fox fits the bill perfectly. But Max has control of his own desire and clearly sees his position in their relationship: he has plenty of money, and, sure, while he waits for sex he’ll drive Fox around so that Fox can get that lottery ticket, but he’s not going to give a dime to Fox — that’s not part of the transaction he has in mind.

Because Max and Fox come from two completely different worlds, it’s surprising to find Fox still hanging around at Max’s home a few weeks later, mingling with Max’s friends who are likewise confused at the uncouth man’s presence. It all makes much more sense when Max tells them, and us, that Fox has made it. He won the lottery. Soon Fox finds himself with a few new friends, including Eugen (played by Peter Chatel) a new boyfriend from the upper class who takes Fox under his wing to introduce him to the finer things in life, like turtle soup, not noodle soup, for example. Waiting on the sideline is Eugen’s old boyfriend Philip (played by Fassbinder regular Harry Baer).

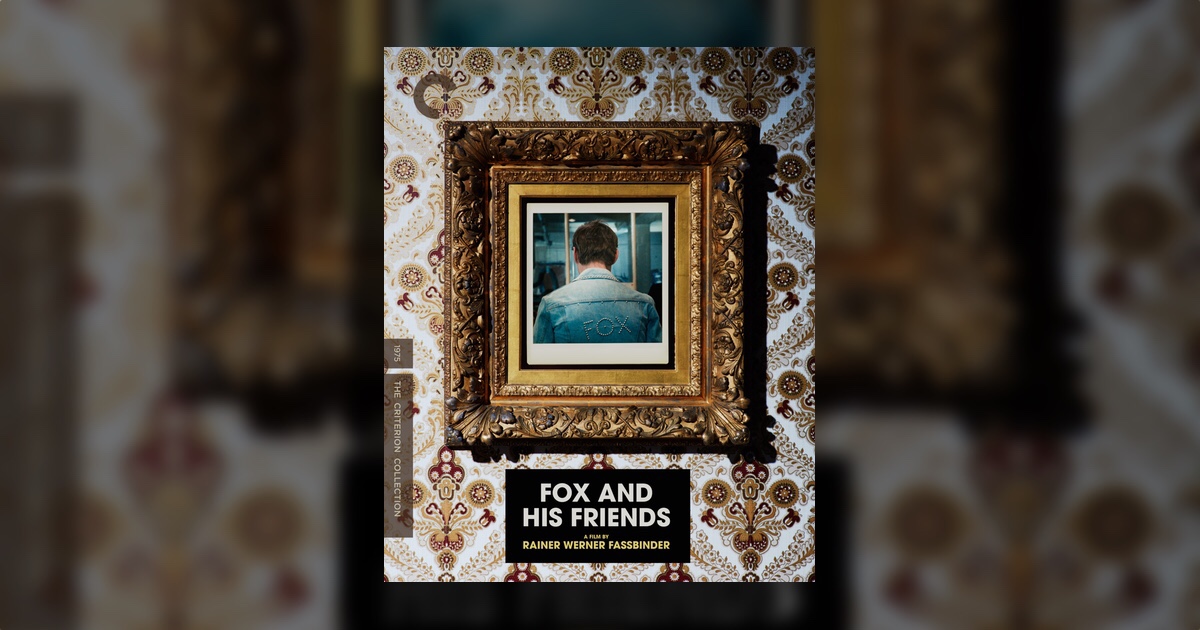

At only twenty nine years old and working at a feverish pace, Fassbinder already had twenty two films under his belt when he wrote, directed, and starred in this cynical yet mysteriously sensitive and controversial film. Today, The Criterion Collection is releasing Fox and His Friends on home video with a sparkling 4K digital transfer taken from the original camera negative. It’s well worth picking up because, though the film deals with Fassbinder’s universal theme — that when two people connect a power hierarchy forms already ripe for exploitation — it does so from a unique perspective and, for the first time in his work, completely within the community of gay men.

Indeed, the film and Fassbinder have received plenty of criticism for the film’s portrayal of gay relationships, but Fassbinder expressed his explicit intention to make a film where being gay was normal and not the cause of any problem; rather, his universal theme is truly universal, and these gay men are as human and faulty as any other. Fox and His Friends is complex and layered and packed with raw emotion.

We’d expect no less from the man who burned through so much life in a little more than a decade, all the while attempting to translate and explore aspects of that life onto film, even aspects that don’t cast him in the best light. As shown in the Criterion supplements, particularly in the conversation with Harry Baer, Fassbinder was the powerful and oftentimes cruel and exploitative focal point of more than a few relationships. In a tragic intersection between life and film, Fassbinder dedicated Fox and His Friends to his lover Armin Meier, who famously committed suicide a few years later in Fassbinder’s apartment on Fassbinder’s birthday. There’s plenty of speculation as to why. In the Criterion supplement Baer suggests that Fassbinder knew well before Meier’s suicide that Fassbinder himself was the powerful member in their unequal relationship and that he was being self-critical in Fox and His Friends: Meier was the exploited Fox. Notably, though, as much as we might sympathize with Fox as his ostensible friends take him for all they can get, Fox isn’t held blameless and, as shown when he interacts with the florist, is just as capable of cruelty. Fassbinder’s sympathy can only go so far.

But as cynical as Fox and His Friends is, Fassbinder’s ability to capture in a gaze the vulnerability, the jealousy, the loneliness of almost every character ensures that it is not completely heartless. Furthermore, there are moments when we suspect a character might be capable of using love — or whatever is being confused as love — as something more than a mere bartering tool, that sometimes sex and money do not function in the exact same manner. Max, for example, who keeps Fox around after he wins the lottery, doesn’t at first seem interested in Fox merely for his money and threatens to be capable of genuine empathy throughout the film. When Max’s friends, soon to be Fox’s friends, ask Max why Fox is around and Max explains that Fox recently won the lottery, it actually appears that Max may be chastising Eugen and Philip a bit, that he could be implying they’ve misjudged the man in his home because they think he’s lower class, but, just like them, he has money.

But these people — all of them — see life as a series of transactions, and they aren’t as interested in character building as they pretend to be. They set the transactions up, give what they are willing to give so they can take all that they are interested in taking. It doesn’t matter if they used up every last bit that the other person could possible give.