When Robert Bresson, in his early 80s at the time, chose to adapt Leo Tolstoy’s short story “The Forged Coupon,” he crafted an efficient, taut film by using only the first part of Tolstoy’s tale, ending when Yvon, our central character, commits an act of horrific violence. Bresson doesn’t venture into Tolstoy’s second part, where, in prison, Yvon seeks redemption through religion. What we get, then, is L’argent, which translates directly to “money,” Bresson’s nihilistic, final film. Redemption doesn’t feel like a remote possibility. Bresson’s films are often bleak, but what’s surprising is that Bresson subverts all moments leaning toward grace in this brisk 84-minute film. Yet, for all its relentless darkness, L’argent is a wonder to behold, invigorating and challenging.

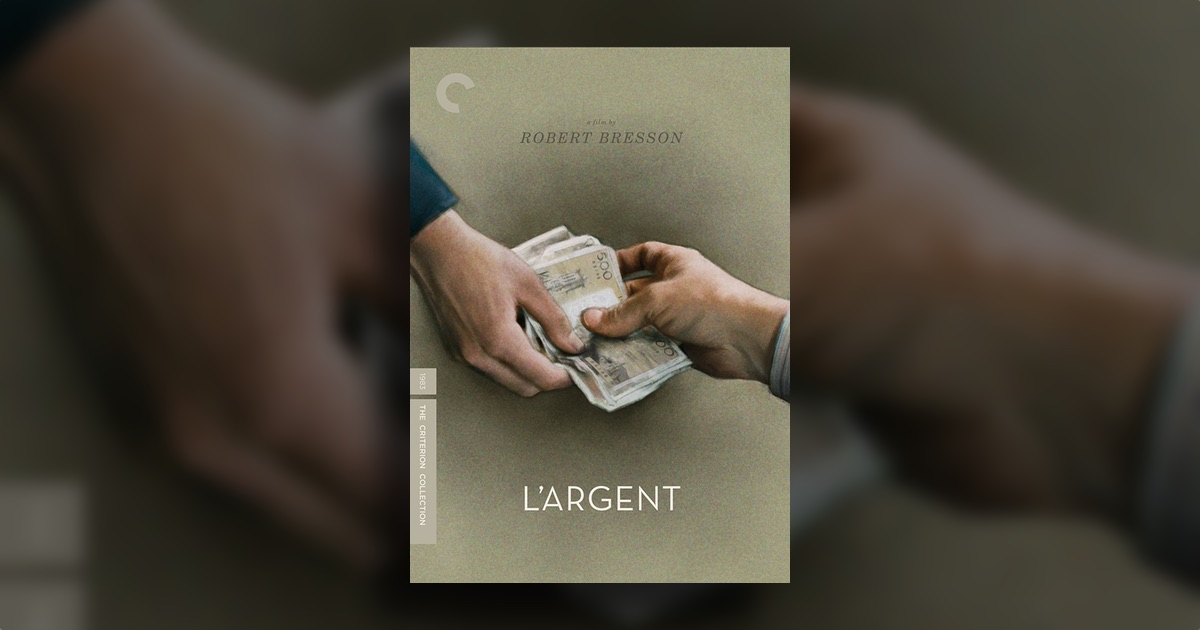

L’argent begins with Norbert, a Parisian teen, asking his father for his monthly allowance. Father looks up, pulls out the money, hands it to the teenager. But, says Norbert, he needs a bit more to pay a friend — already the hand-to-hand transfer of money and, with it, the weight of consequence is established. With Bressonian stripping down of emotion, the father turns Norbert away. Norbert’s search for funds sets in motion the machinery of L’argent: Norbert needs money; to get money, Norbert passes off a friend’s forged note at a photography shop; the shop owner passes the forged note to the innocent gas worker Yvon, who will be betrayed, arrested, destitute, jailed for a botched bank robbery, abandoned, an so on. L’argent links event to event, escorting us finally to what looks like a more peaceful life in the country. This turns out to be an illusion.

Money — the lack of it, the desire for it, those who seek it — corner an otherwise innocent, passive, random man, removing him from the life he created to one he must react to. It is a tale of cause and effect, but rather than allow reasons to become excuses, Bresson adds a great deal of detail and texture to enrich and explore rather than simply present the story of a man’s moral degeneration.

In L’argent, Bresson makes full use of his stripped-down acting aesthetic, a technique meant to achieve intense minimalism. And so, when Yvon is accused of forgery, the actor, Christian Patey, doesn’t show anger. When those who know lie, Patey simply looks on. When the judge chastises Yvon for slandering honest people, nothing flashes over the actor’s face.

This technique may cause the acting to feel stilted — which it may be, Bresson directing his actors to barely recite their lines, faces neutral, emoting nothing — but the technique yields tremendous riches. Instead of creating a barrier between the audience and the dramatic action, when Bresson strips away he forces our attention to new details. Often the camera looks only at feet, torsos, and other headless figures, the bodies as roving objects, only slightly attached to a mind.

We also get the Bressonian scrutiny of gesture, of hands, the main, delicate instrument of volition, perhaps our main key to the characters’ psyche. In L’argent, we see hands as the main way to connect with another person. Whether it’s exchanging money or contraband, pushing someone away, wielding an ax, or sharing a nut, the hands in L’argent allow Bresson to explore the characters by heightening our attention to the detailed ways the characters use hands to interact with the world around us.

Remarkably, Bresson’s restraint and focus opens up the characters to us in a way that is unique and, more importantly, keeps them open as our response to the films evolves over time. This is why I think L’argent is much richer than we might expect if we think of it as primarily a chain of cause and effect, or a money-is-the-root-of-all-evils moral tale. Bresson is fully in control but his method allows us to formulate our own rich thoughts about what is happening, and why. Who is Yvon when the story ends? What games of chance are happening here? How does the passive victim become the obverse? For money? Sure, he says as much. But the money is the means to examine a lot of other aspects of the human condition, and I’m glad Bresson didn’t think we needed a prison scene with Yvon finding his soul. This is the story of a soul embattled, beaten or giving up.

The Criterion Collection edition is not particularly stacked with supplements — indeed, it has only three: footage from the 1983 Cannes Press Conference when Bresson and the cast take questions, James Quandt’s visual essay L’argent: A to Z, and the short trailer. However, I was still happy with what we did get. In the Canne footage, Bresson and the cast talk about their own interpretations of the film — Bresson even saying where he sees good cropping up at the end — and we get to see the octogenarian’s increasing annoyance with the crowd. James Quandt’s visual essay is a lengthy — just over fifty-minute — essay that looks at 26 attributes of Bresson’s work. I found this as insightful an exploration of Bresson’s world as I’ve seen, and I would have loved it twice as long. All in all, despite the low number of supplements, we get some nice context for the exceptional film.