In the late 1960s, Sergei Parajanov, a Soviet director of Armenian descent, was set to make a film about the famous 18th-century Armenian poet and troubadour Sayat-Nova (a kind of pen-name that means “Hunter of Songs”) to celebrate the poet’s 250th anniversary. Right from the opening text, those who commissioned the work must have been surprised and maybe a bit worried. It boldly states:

This film is not the story of a poet’s life. Instead, the filmmaker has attempted to recreate the world of a poet — the modulations of his soul, his passions, and his torments — broadly utilizing the symbolism and allegories of medieval Armenian troubadours.

This introduction to the film, however, fails to sufficiently place the viewer on notice. The Color of Pomegranates is a startling departure from the traditional biopic. It really cannot even be called a departure since it is clear this was never on the path of a conventional biographical film in the first place. Even if we consider another “biographical” film that also chose to convey the world of an artist rather than the life of the artist — that film being Andrei Rublev, made by Parajanov’s contemporary and friend Andrei Tarkovsky — The Color of Pomegranates is completely unique, a sui generis film that has now made its way onto a stacked home video release from The Criterion Collection.

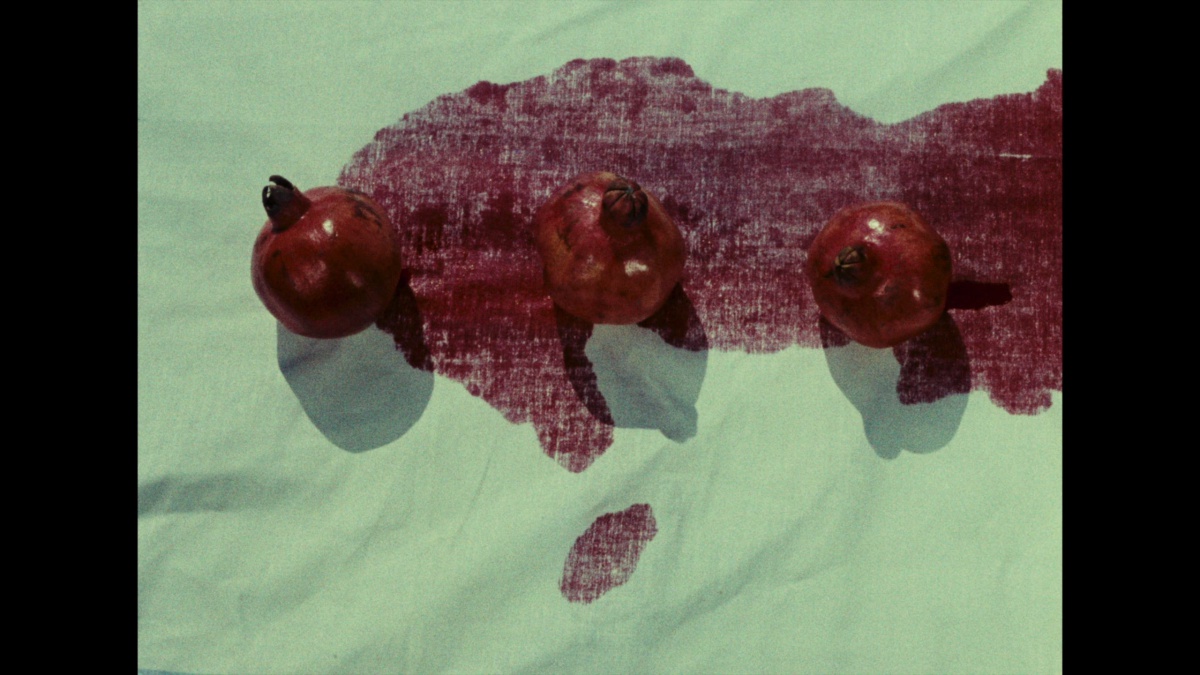

The film opens with the above shot of three pomegranates on white cloth. The juice from the pomegranates slowly bleeds into the cloth to form the shape of Armenia. The next image is a more sinister knife on a white cloth, upon which a red stain grows as well. There should be no surprise that this film had a hard time getting past the Soviet censors. These initial images are mysterious and compelling, but they are also discomfitting, the film potentially insidious.

Beyond that, the entire film is a series of densely packed tableaux, and in 1969 the state-mandated aesthetic style in the Soviet Union was socialist realism, which had been enforced to varying degrees for nearly four decades: art should be easily understood by the people and should convey a positive message about the State. On first glance, the film can appear impenetrable (though I’d argue it is still enticing and engaging). Here is an early example of the tableau style Parajanov employs throughout:

Armenia is situated in Transcaucasia, the area around the border between Eastern Europe and Western Asia, and has been heavily influenced by all of the converging cultures. Indeed, during Sayat-Nova’s life, Armenia was both part of the Ottoman Empire and the Iranian Empires, to varying degrees from time to time. Towards the end of The Color of Pomegranates we see the Persian invasion. Add to this Armenia’s own ancient culture of wine-making and oil pressing, as well as its history of Christianity, and we have a region of almost unparalleled diversity and richness. Such is the world of Sayat-Nova, east and west, Christian and Islamic and Persian culture, ancient tradition and the modern world, all blending together. The film is packed with references to all of this, inviting us to feel the bounty while situating symbols and life in such a way that we contemplate the myriad relationships.

In The Color of Pomegranates, Sayat-Nova’s life is divided into parts, each part, from his late childhood and early adolescence to his death in old age, played by a different actor. Fittingly, the script that introduces his childhood tableaux is this: “From the colors and fragrances of this world my childhood fashioned a poet’s lyre and offered it to me.” And so we see a childhood of weaving and dying carpets, of visiting the sulfur baths, and, for me most emphatically, of books and religion. Here is young Sayat-Nova, before he has that name, watching the books dry out after a flood, presumably already sensing the treasures within.

The set-up of these scenes is beautiful, evocative, mysterious, hypnotizing. And while the scenes are largely static like a tableau, there is often movement within the frame: wind pushing trees or turning pages, water trickling down the walls, individuals performing some ritual motion or even swinging back and forth as if on a pendulum. Strangely, all of this motion within an almost motionless frame suggests just how vibrant and vivid any moment of life can be to someone taking it all in.

And thus we get Sayat-Nova the poet, given his instrument and eventually moving to court.

After quickly building a reputation for his music, Sayat-Nova was called to court and remained there for much of his early adulthood. In this portion of the film, he is played by the actress Sofiko Chiaureli:

Importantly, in this very same segment, Chiaureli also plays the role of Sayat-Nova’s love, the Princess Anna (she plays at least six roles in the film!):

This is a fascinating segment of the film for so many reasons, and it is illustrative of the multiple threads being weaved in The Color of Pomegranates. First, there is layer upon layer of symbolism as Parajanov shows the strained courtship of two people who love each other but who are not thought suitable by bystanders, each played by the same actress. Its ingenious.

But this particular segment of the film is also looking at masculinity. Is casting a woman to play this portion of Sayat-Nova’s life as a poet suggestive of a more feminine calling? Is it more androgynous and critical of presumed gender roles? This is underscored at one time when it seems Sayat-Nova will forsake his instrument to become a hunter, adopting a more traditional masculine role.

I’m not exactly sure how much of the interest in gender roles comes from the poet’s life in 18th-century Armenia and how much of this exploration comes from Parajanov’s, but it is definitely safe to say that beyond Sayat-Nova’s world and culture Parajanov mixes in his own memories and feelings as well, including, for example, a moment when the wind blows the top off a cathedral. It adds to the richness of the film, to me, giving so much to explore, so many things to consider in their relation to other things.

This is a good time to stress that while Sayat-Nova is presented throughout The Color of Pomegranates, and we can pinpoint some general times in his biography, this film goes much further into its exploration of the feelings — the day-to-day life, the culture, the spiritual yearning, the tragedies — in the history of Armenia. As I mentioned earlier, we see the upcoming Persian invasion from the late 18th-century in the latter part of the film, but the film also contains elements that call to mind the many other tragedies that have befallen Armenia, particularly the more recent Armenian genocide of the 20th-century.

As the film proceeds, I actually think the imagery becomes more breathtaking. For example, the early adulthood of Sayat-Nova ends with a death of a sort — his exile from court (presumably because of his relationship with the Princess) — and we see ashes blowing all around Chiareli’s poet before we bid her farewell (for a short time):

Sayat-Nova moves to a new calling as a particularly devoted and ascetic monk:

This segment of the film explores the vast questions of the spirit and of religious belief, especially as death comes along. We watch Sayat-Nova dig a grave for his bishop, while a flock of sheep come into the frame and meander around him and the body. We see Sayat-Nova strip his black vestments to stand in sack-cloth. We see an empty cradle enter the frame, representative of these men and their vows of celibacy, as well of of Sayat-Nova’s own terminated relationship with Princess Anna. We see Sayat-Nova dream of his younger self, and we are not sure if it’s a fantasy or a nightmare. We see Sayat-Nova become an old man, trying to drink from a dry font, mingling with the common citizens again, until he once again adopts the name Sayat-Nova, leaving behind his religious attire and picking up, at long last, his instrument.

Because the film is dense and it is helpful to know a bit about what is being presented in the tableaux, I strongly recommend the new Criterion edition. It is sources from a 4K digital restoration performed by the saintly World Cinema Project of The Film Foundation in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna, and it looks and sounds beautiful, especially for a film with its history of mishandling. But beyond that, we get a rich and insightful full-length commentary by Tony Rayns. This commentary is a pearl. Another feature that helps us see more of the riches of the film is James Steffen’s video essay on the symbols and references in the film. These supplements are not necessary to being hypnotized by the film, which I think works well as a piece of poetry on its own, but they are vital to anyone who, after watching the film, has a desire to really dig in and explore the images. Other interesting features include documentaries on Sayat-Nova and Parajanov. This is a beautiful edition of this one-of-a-kind film.

The Color of Pomegranates is a marvel. Its images feel particular to the life and times it is ostensibly exploring and yet applicable to the vastness of Armenian history. I’d argue they are also compelling and evocative to our modern eyes, even we who do not know much about Armenia and even less about Sayat-Nova, because they are general and provoke rumination on our own life with its haunting symbols. In every segment it asks us to consider how various external forces form our experience and create our world.