Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones is a transitional film. At the beginning of his career, Richardson was building a name for himself with tight, kitchen-sink realism films about down-and-out middle-class British, like 1959’s Look Back in Anger, 1960’s The Entertainer, 1961’s A Taste of Honey, and 1962’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. Then, seemingly from nowhere, came Tom Jones, a complete departure. Here we have a period piece adapted from Henry Fielding’s massive 1749 novel. Not only is it quite different in material, but the film is mostly a picaresque comedy, with a lusty but good-natured protagonist who is far from the angry young men dramas that inspired Richardson’s earlier films.

The film is also emblematic of a transition in British film in general, getting away from the more serious dramas to comedies that were playfully absurd. If a short film like Richard Lester’s 1959 comedy The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film was making ripples, Tom Jones came in and made a splash, even winning Best Picture a year after David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. Where Lean’s film is stately, serious, and epic in technique and visuals and tone, Richardson’s trims a nearly 1,000 page novel to 128 brisk minutes and utilizes a host of comic touches that foreshadow Monty Python.

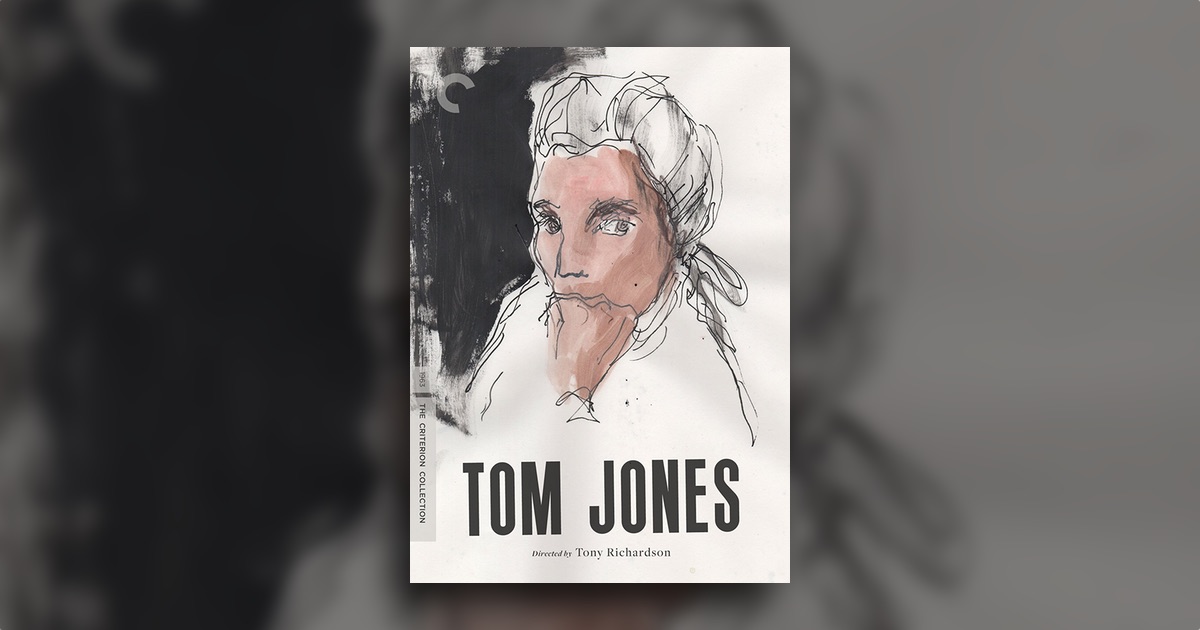

For Tom Jones, Richardson cast the young man who’d debuted in Richardson’s The Entertainer, the versatile and amiable Albert Finney:

The film begins with an homage to silent film. Though shot in lush color and in a beautiful courtyard, the opening plays a jaunty harpsichord score over a bustling scene. Squire Alworthy is returning home, we learn via intertitles.

But, what’s this in his bed? A baby boy with red hair. After learning, they think, the poor boys questionable parentage, Alworthy decides to raise the young “foundling” as his own son.

Tom grows into the dashing young man who loves to go hunting in the woods. For what? Well, that’s when we see just how popular he is with the ladies. But as lusty as Tom is, as much as he must deal with the stigma of an illegitimate birthright, Tom has a kind heart that doesn’t take seriously the many forces that would try to oppress him, represented primarily by his tutors, Mr. Thwackum (Peter Bull) and Mr. Square (John Moffatt), and by Blifill (David Warner in his debut), Squire Allworthy’s nephew.

While the story is developing we also meet Squire Western (Hugh Griffith) and his daughter Sophie (Susannah York). Hugh Griffith, by the way, is delightfully earthy in this film. By anecdote, we learn that he was often a bit tipsy with drink during filming, and his Squire Western is a man who obviously has never been told to grow up. It’s not that he’s an idiot; he just doesn’t need to hold back as much as most people would. Look at him here, with some of the chicken in his hair:

It’s no surprise that a large element of the film is the relationship — the forbidden relationship — between Tom and Sophie. They are friends, but Tom’s illegitimacy officially renders her out of his league, even if they delight each other consistently, enjoying the beautiful world around them:

Alas, as they discover they love each other, everyone else thinks her natural place is beside the boring, mean-spirited Blifil. Tom is forced to exile.

This is what takes us to Tom’s journey, another major element of the film. There are sword fights, soldiers, injuries, etc., but along the way there is eating and love-making, each encapsulated in the film’s most famous scene, the one in which Tom eats across the table from the older Mrs. Waters (Joyce Redman):

They get increasingly ridiculous until they are unabashedly lapping up the juices of everything they eat. It’s hard to look away, though it’s uncomfortable to watch two people caught up in their animal instincts and unaware of anyone outside of their gaze.

Tom Jones is not afraid to confront its viewers with provocative imagery, but it balances things out nicely with its good heart and by acknowledging not everything is easy going lust.

Tom Jones is a strong film, and I think it’s easy to see why it called to critics and audiences back in the early 1960s. By today’s standards it may be tame (the narrator at the beginning states that out of a sense of decorum the film would not show Tom’s more lascivious acts — at least, not literally, though the dinner scene certainly feels as inappropriate as any love scene from the 1960s you might imagine), but it still feels fresh because the silliness and the story work so well together, and its star, Albert Finney, so capably works in any mode the film demands.

That said, its Oscar win may impose an unfair weight on it. Nah! I think it’s strong enough to hold up, and this is a packed Criterion edition that looks at how the film came to be and how it left its mark on British cinema. Also, this two-disc set contains both the theatrical release and the editor’s cut that Richardson released in 1989. Richardson was never satisfied with the original version (and indeed seems to agree with critics that the film is a bit of a trifle that shouldn’t have been as popular as it was). In a misguided effort to, I don’t know, improve it, one must assume, he ended up cutting eight minutes and completely botches the rhythm. I feel Richardson only harmed his film with this 1989 version. For example, he cuts moments from the montage where Tom and Sophie fall in love and experience an idyll with no regard for the future, including the wonderful moment when they drink the rain together. That brief moment does so much to show their comfort with each other, as they enjoy the world around them, and I cannot get behind any version that cuts it. That’s one example. But I’m glad we have both versions, and there’s a nice supplement where Robert Lambert, who helped with the cut, explains what Richardson was going for.

So, in case it isn’t clear, I highly recommend you seek out Tom Jones and allow yourself to be entertained by its intoxicating combination of irreverence and purity of heart.