With a film like Like Someone in Love, it’s difficult to compose your thoughts into an intelligent and insightful reading simply because it is able to perform such a subtly extraordinary sleight of hand—cinematic or otherwise. It is perhaps one of the most conversely simple yet emotionally substantial films I have ever seen, and one whose meaning will tend to change depending on whom you ask. After watching the film myself, my girlfriend asked me what it was about and I could give her no less than an hour-long answer if I tried, and yet I could tell you right now—all in one sentence—that it’s about an interaction involving a young female prostitute and an elderly male professor in Yokohama, Japan who end up further entangled in the volatile emotions of the girl’s jilted boyfriend following the previous night’s enigmatic encounter. On the one hand it is outwardly simplistic, but on the other it is a wellspring of philosophical and sentimental feelings that play out behind a steadily unraveling plot. In short, it is an Abbas Kiarostami movie through and through.

The raison d’être in Kiarostami’s four-decade body of work so far is the mischievous divide between seeing, believing, and being, whether it involves a pseudo-documentary about man impersonating a prominent film director in Close-Up or two apparent strangers strolling—and driving—through the Italian countryside only to reveal a potentially unsaid history between the desensitized pair in Certified Copy. His films ponder the ultimately unknowable but delicately familiar interactions of the human spirit, a spirit that tends to define identity as if such a fundamental label were as fluttery and insignificant as gossamer but extraordinarily important nonetheless. The main thing to remember about Kiarostami’s movies is that they don’t operate on the pretense of a futile twist or a gotcha moment, but rather they let their expressionistic reality wash over you organically. They are working on you as much as you are working on them.

Some will presuppose that a movie like this will be boring simply because they have to do a bit more than just watch it, and those people (God bless them) would be right themselves, but Kiarostami’s tendency for long takes and enigmatic narratives should do the complete opposite of bore those willing to exist with the characters. Such a readiness to participate unveils an essential part of Like Someone in Love—that of movement and repose, of stillness and disruption. Kiarostami seems to be saying that such a back-and-forth is indicative of life in the modern world—typified by the film’s portrayal of constantly shifting connections between old and new generations—and that the way we live our lives is defined by an existential seesawing characterized by such disruptions. Such subdued turmoil could be as simple as a phone call cutting a conversation short, a shrewd disagreement between two people, or unexpectedly meeting someone you haven’t seen in a very long time. On the other hand, that turmoil could be present in very complicated situations such as a daughter’s intentional absence in a family, or the death of a loved one.

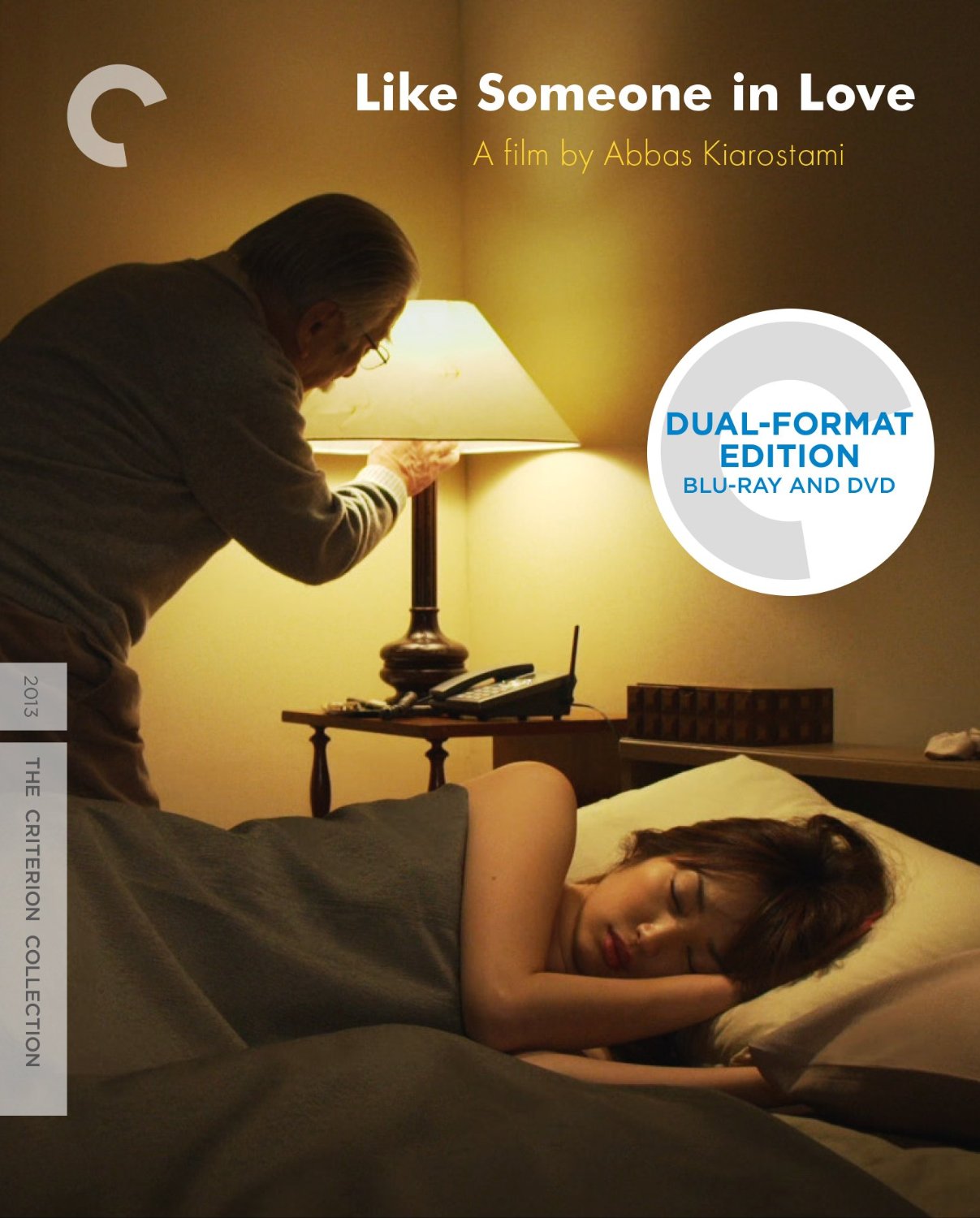

The core meeting between Akiko (the young girl, played by Rin Takanashi) and Takashi (the elderly professor, played by Tadashi Okuno) takes on a surreal quality while presenting an outwardly normal conversation. We must solely gather important information from objects themselves like photos or the piles of books strewn about his apartment, but also from reactions in conversation or the subtlest of glances. Perhaps the best dramatic moment in the film is a slow exhale by Takashi after Akiko declines his invitation to sit down for dinner. Part of the film is all about expectations by the characters within and the audience themselves. Whether Takashi decides to sleep with Akiko is a narrative fulcrum that lesser directors would agonize over or strain to emphasize, and yet Kiarostami lets it play out as normal. We expect it to be a point of dramatic importance, but instead it emphasizes the banal—but important—emotions and movement of everyday life.

Criterion’s release, like the film itself, is deceptively simple. Aside from the trailer and the sometimes overly-theoretical essay by film scholar Nico Baumbach, the sole supplement is a forty-five minute documentary on the making of the film made by Kiarostami himself. But instead of throwaway fluff, it’s rather an essential continuation of the film itself. We see Kiarostami—shooting footage with a small digital camera—interacting with the actors and fleshing out scenes by imploring them to do whatever they would do as if the situation were happening to them in real life. Numerous times throughout the doc we are reminded that the actors haven’t seen a completed script, followed by Kiarostami’s implication that the script itself was only ever an outline from which he would mold the story in collaboration with his actors. Another essential part of the doc is the fact that Kiarostami doesn’t speak Japanese, and the suggestion that he made the film in a language he doesn’t understand in order to separate the emotional heft of the story from any sort of comfort that the limitations of language could somehow ruin. Funny enough, when directly asked why he set the film in Japan, Kiarostami responds saying, “Sushi.”

It’s almost meaningless to say a movie rewards multiple viewings, and it would be restrictive to say that multiple viewings of Like Someone in Love would somehow make you understand it better. Instead, multiple viewings of Like Someone in Love will simply allow you to follow the characters again and again, and in turn will naturally reveal the volatile emotions at play within human desires through these characters. The film is admittedly not for everyone, but those who are at least interested in Kiarostami’s masterful explorations of appearance versus reality will find as much or as little here as they want.