I’m not sure why it is, but whenever Criterion announces their new slate each month the Blu-ray upgrades are always a bit of an initial personal letdown. My knee jerk reaction, which nevertheless continues on seemingly with every monthly announcement, is why dwell on the old when you can bestow the coveted Criterion Collection stamp of approval upon countless other unheralded cinematic gems out there? With their upgrade of Erik Skjoldbjærg’s Insomnia, I finally fully understand the imperative need to revisit, remaster, and restore the older titles in the Collection, even if nobody is immediately clamoring for them.

Skjoldbjærg’s enigmatic thriller is a murder mystery surrounding Jonas Engström (a steely blank but spot-on-perfect Stellan Skarsgård) a psychologically haunted and morally grey Swedish detective called to a perpetually sunny small town in northern Norway to investigate the puzzling murder of a 17-year-old girl. Like all of the best and most intricate murder mysteries, this slow burn story doesn’t depend too much on the whodunit details, and reveals otherwise key points like the identity of the killer fairly early on. Instead, the psychological exploration of those unknowingly pulled together by the orbit of the morbid incident itself reveals the story’s true narrative weight, transcending clear cut good and evil to create a unique point within the many similar detective stories that have come before and after it.

Initially the basic subtext suggesting the indistinct nature of good and evil seems relatively redundant considering the detective genre itself, but Skarsgård and Skjoldbjærg focus their attention on making Engström’s unnerving detachment and personal demons the film’s singular factor. He’s a man who is completely individualistic, almost heartbreakingly so to the audience willing to go along with him, and what’s worse is that Engström himself knows it and can’t really do anything about his faults besides dig himself deeper.

Along with its sometimes-disorienting camerawork or flashes with the surreal, the film’s stark white backgrounds and cold bluish tint (filmed in Skjoldbjærg’s hometown of Tromsø, Norway) provide the perfect canvas on which to paint the ill-fated mystery. It not only plays into Engström’s increasingly overwhelming inability to fall asleep during the 24-hour sunlight above the artic circle, but also the utter isolation of the character’s total being both inside and out. The only true acting we get is from Skarsgård’s piercing eyes, and his performance is perhaps only really done through those windows to the soul. It seems no matter where his character flees, his own reprehensible actions inevitably catch up with him, and even when he seems to absolve himself in both slight or major ways—like when he attempts to strike up a friendship with an innocent receptionist at his hotel or plainly solving the entire mystery by deducing the identity of the killer—his actions never fully exonerate him from past and present sins.

Skjoldbjærg’s Insomnia seemed like an outlier at spine #47 nestled in between bigger names like Kurosawa and Fellini, and to a certain extent it is, but being the outsider among such esteemed company shouldn’t dissuade one’s initial opinion as it did mine. Rediscovering Insmonia has been one of the best surprises of the Collection for me this year, mostly due to the release’s total revamp, and my hope is that people will take a shot and rediscover it too because it is definitely worth it.

The look of this film is among the most important aspects about it, and the 4K digital restoration is probably the best thing to happen to the film since its original release; the previous one was sorely lacking in the quality department. The film is stylistically blank on purpose, and having that crystal clarity does away with any muddiness that would hide that ingenious directorial choice. It brings the flat solitude of the characters to the forefront and basically makes the film itself better to experience.

The package is otherwise light on the special features, but anything more than what’s included would have been overkill. First up is a 20-minute conversation between Skjoldbjærg and Skarsgård that begins on a jovial note between the two collaborators and then segues into a brief history of the sometimes-troubled production for the first-time director. The stoic Skjoldbjærg—who was the first Norwegian to attend the National Film and Television School in London—recounts his equal mix of arrogance and confidence in tackling his first feature, and the fact that he purposefully surrounded himself with many veterans to make up for any of his obvious flaws. Skarsgärd’s seemingly candid take on his experience—like when he admits that he originally hated the script—is surprising, but it transitions into truthfulness when you realize his perspective is from someone who has only seen the movie twice (the second time for the interview itself). Overall the interview is enlightening if not a bit awkward.

Both short films included with the release, made while Skjoldbjærg was a film student, are surprisingly excellent additions. Both are tangentially related to the main feature in mood and aesthetics but gripping in their own right. The solemn Near Winter tells of a young Norwegian man returning home to an isolated farm with his English girlfriend only to find something is wrong with his hermit-like uncle who lives there and who is prepping for the coming winter. It’s the more measured of the two, and has a real discomfiting sense that fits nicely with the bucolic, almost Tarkovskian, photography of the Nordic lanscape.

The second short, and the one more similar to Insomnia, is Close to Home. Itself a kind of detective story or police procedural, the film is instead told from a suspect’s point of view, and is about a man who offers to help out a young woman thrown out of a nightclub while he is walking home one night. Later we find out that she has been raped, but it is initially left unclear to the audience whether the suspect did it or not, making us call into question our own understanding of the film’s twisting perspectives. It’s a clever and twisted little film that took me by surprise in the best way, and reminded me of the knowing grittiness of early Christopher Nolan films (Nolan actually went on to remake Insomnia in 2002 starring Al Pacino and Robin Williams).

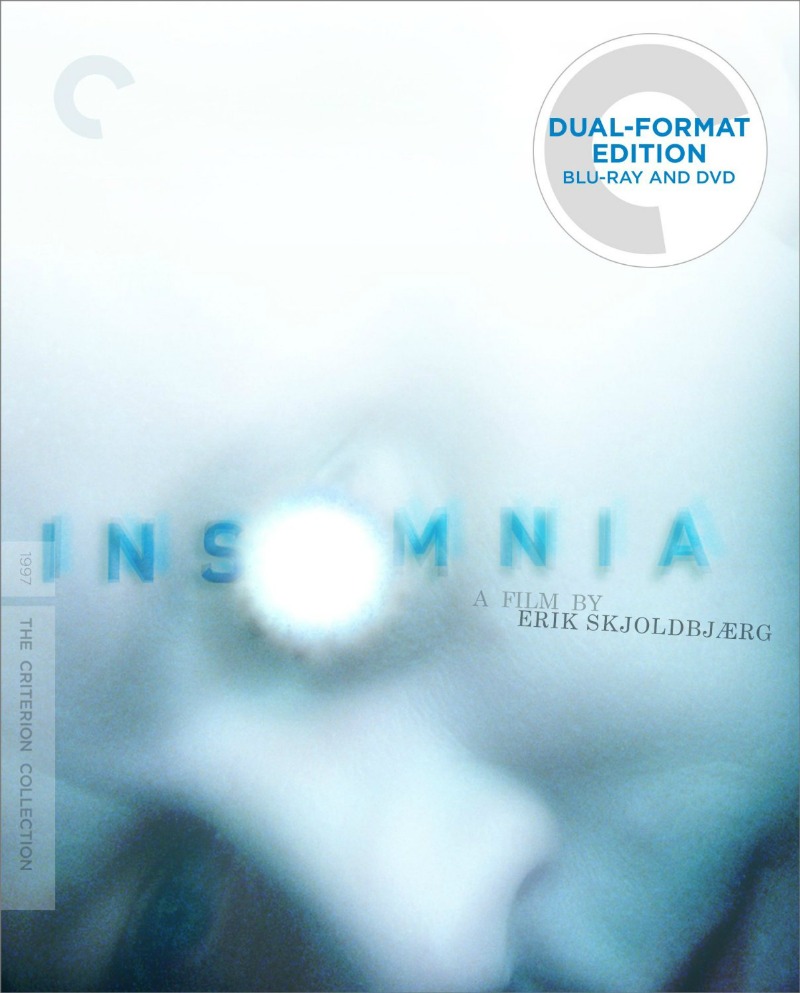

Other than the trailer and an essay by critic Jonathan Romney (one that skewed so close to my own reading of the film that I hesitated to even write this review so as not to just blatantly reiterate what he says), the other notable detail about the release is the art design. The Criterion website’s thumbnail doesn’t do it any justice whatsover, and along with the ingeniously designed inside booklet the package is one of those perfect examples of Criterion covers that are undeniably linked to the movie they represent. Check it out in person and you’ll know what I mean. It’s one of the best of the year.

I was surprised by Insomnia, firstly because I kind of wrote it off before even seeing it again, but mostly because it is an expertly made downbeat thriller that anticipated similar Nordic-set detective stories that seem to be more and more popular nowadays. It’s hard sometimes to get lost among the embarrassment of riches that Criterion lets loose month after month, and Insomnia may have fallen easily out of view for many people. But don’t be fooled, it’s a great release that I hope is rightly rediscovered.