One wonders whether Lars von Trier prefers being a provocateur to being a filmmaker, or whether or not he thinks those two labels are mutually exclusive. He’s made an entire career out of cleverly thumbing his nose at the audience within the realms of his films and in real life, successfully creating something of a completely unique circus-like atmosphere surrounding himself and whatever he comes up with. Make a movie about the end of the world? Sure. How about I throw in some genital mutilation and talking foxes in a horror movie about the inherent pessimism of the human spirit? Yeah, why not. What about a four-hour epic chronicling the complete sexual life of one woman? Sounds intriguing enough.

He’s a guy whose mantra starts out with a small kernel of an idea that’s bound to piss at least someone off, and then runs wild from there. It’s an admittedly reductive look at someone’s filmography, but it isn’t too off the mark when you boil it down. Occasionally his confrontational method and the essential ugliness found in his films works, but sometimes, like in Nymphomaniac, the idea is much more compelling than the heavy-handed, narratively simplistic, and conceptually superficial realization.

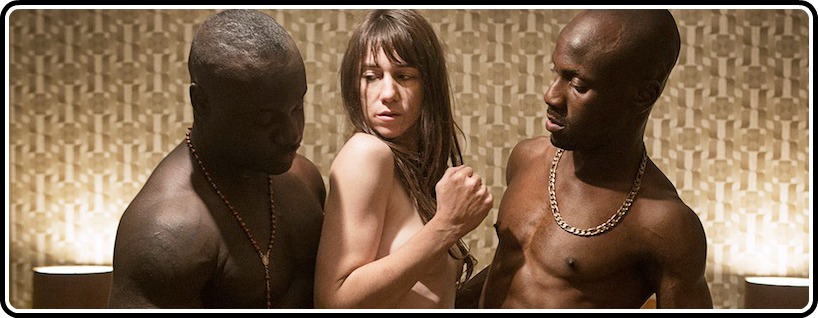

Essentially one story broken into two nearly arbitrary halves, the film tells the tale of Joe (von Trier’s recent actress-of-choice, Charlotte Gainsbourg), a self-professed nymphomaniac who we find beaten and bloody in an alleyway before she’s soon discovered and comforted by a hermitic intellectual named Seligman (von Trier veteran, Stellan Skarsgård). They soon retire to his unadorned apartment and engage in a series of conversations about her ignominious deeds narrated in a somewhat distracting monotone by Joe herself and revealed over the course of eight cinematic chapters spanning her entire life. Every now and then the prudish Seligman—later drolly revealed to be a virgin—interjects with dry academic commentary, which is basically the only way he knows how to try to comprehend what he’s hearing.

The narrative technique von Trier’s uses between Joe and Seligman has been likened to Socratic dialogues where two characters discuss moral and philosophical problems to ultimately arrive at some sort of legitimate ontological truth, and on the surface it’s a fairly apt comparison, yet their conversation predominantly veers towards frustrating and overly obvious metaphors and allusions instead of genuine philosophical concepts that actually engage with the film’s themes. One of the most egregious examples is the oddly dumb metaphor comparing the men that Joe and her friend try to fuck on a train to catching fish swimming in a stream. Otherwise, one can’t simply mention things like the Bible, Jesus, Andrei Rublev, the Fibonacci Sequence, Bach, Beethoven, and—bizarrely enough—James Bond and have it be discourse, and yet the film masquerades these asides as if they are a meaningful part of the whole.

Anybody who claims that they can find an intelligent connection between them all are desperately grasping at straws, and anybody who suggests that the second volume of the film somehow answers the shortcomings of the first are either willfully ignorant of what they saw onscreen or engaged in the same clinical provocation as von Trier.

If anything, the film is a highfalutin’ mouthpiece for von Trier’s own ideas masked behind the overtly sexual subject matter. Whenever Seligman speaks it comes across as a random page out of LvT’s diary, or something that he just needed to get off his chest so he decided to throw an intellectualized version of that personal history into the script. Any overarching statement about sexuality or female agency is merely a secondary characteristic to von Trier’s grander statement about being misunderstood via his art. Most of it, though, is suffocatingly didactic and seems tenuously associated with Joe’s problem.

But Joe doesn’t see her “problem” as a problem. By “problem” I mean the destructive and cynical sexual power she wields on others and herself. She begins the film by saying outright that she’s a bad human being, and then proceeds to not change from there. It isn’t necessarily sex as a normal impulse versus sex as a perversion to her. The normal impulse is the perversion. Sure she goes through a slight shift—the split between the two halves happens when volume one ends with Joe losing the ability to orgasm and volume two basically deals with the unorthodox ways she tries to accept it but craves getting it back—but the frustrating tendency the film has in defining Joe’s steadfast defiance—or even heroism—clouds any moral judgment one could have other than that von Trier means to say there cannot be any moral judgment at all. If it takes this long to come to such a simplistic—and nihilistic—conclusion then it would seem the whole thing is in vain.

Despite the fact that I wasn’t taken with the film, it does strangely invite a magnetic flurry of interpretation. Some of the best movies, after all, are the ones that you could talk about forever even though you didn’t really like them. The whole affair seems to be von Trier’s definitive treatise on loneliness and the ultimate destructive power of the body, and that at least is the most engaging part. Joe’s desire for any fundamental emotion leads her to many, many sexual extremes, and it just so happens that such behavior is in her nature. She can’t change not because she won’t change, but simply because she can’t—this sounds dumb on the page, but it’s true. This degradation of the body is akin to the non-political aspects of something like Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, another film whose controversial provocation still shocks people till this day. But where Pasolini’s button-pushing seems necessary to the thematic elements of the film, Nymphomaniac just wants to push buttons and see what sticks. Furthermore, Joe’s immovable disposition makes the movie itself as haplessly obdurate as she is.

Shia LaBoeuf and his terrible half-British/half-Australian accent aside, the film does feature a surprisingly effective ensemble. Skarsgård’s Seligman offers some darkly silly beats, leading me to believe that this is von Trier’s best shot at a sex comedy because how else are we to understand some of the inherent ridiculousness in all those scenes? Uma Thurman’s brief, unhinged appearance in one of the early chapters as a wife whose husband leaves her and their three sons for Joe nearly steals the entire movie. Jamie Bell, who features in the film’s most off-putting chapter, also pulls off the extremely difficult task of making a male dominatrix seem slightly human and maybe even a little boyishly charming.

Gainsbourg’s older Joe tends to be so desensitized that she barely registers—this is most likely on purpose—but newcomer (no pun intended) Stacy Martin as young Joe is the mad center of the film’s first half. This isn’t to say that the copious amounts of nudity and sexual acrobatics her character takes part in somehow makes her a “brave actress” for “putting herself onscreen” or something like that that some out of date critic would say. No, what makes Martin the best part of the film is that she’s able to make Joe’s unprincipled actions strangely compelling. If only she didn’t crumble under the weight of the rest of the film’s shortcomings from there.

It’s an exhausting endeavor to sit through four hours of film and come up without much to hold on to, especially in a movie like this which ostensibly claims its capital-I importance based on all of its intellectualized excesses. I just found that it wasn’t worth all that if we’re left with any of von Trier’s insubstantial main points. Yes it’s something of the absurd that compels us to love or lust, and some people buy into that and some people don’t. As with all of von Trier’s provocations there is a certain assemblage of aesthetic beauty in the imagery up onscreen, but this time around I think I’ll just quote one of Joe’s lines and say “I think this is one of your weaker digressions,” because I couldn’t agree with her more.