David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

As William Greaves declared, “it’s important that as a result of the totality of all these efforts, we arrive at a creative piece of cinematic experience.”

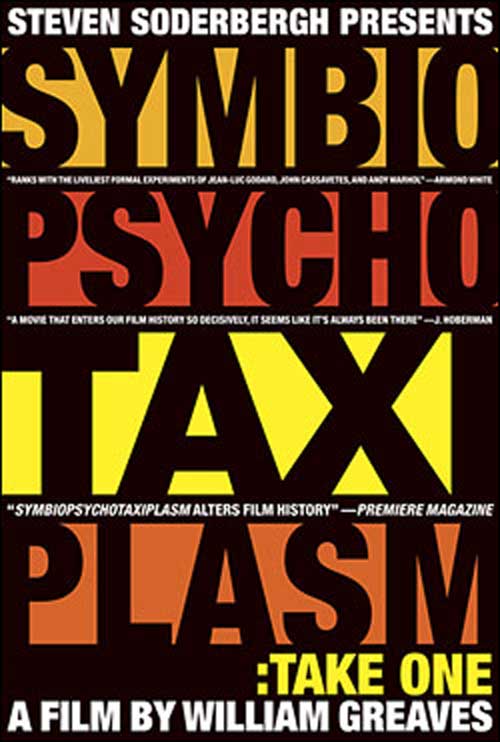

The same could be said of any movie, I suppose. But the sentiment expressed above is especially applicable and indicative of the net cumulative impact that resonates in the sensory receptor system of individual viewers of that hilariously salacious film known as Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One, filmed in the summer of 1968 on a lawn in Central Park, New York City, and also in a few relatively nearby locations including a room situated in an undisclosed location (presumably somewhere in Central Manhattan) where members of the crew gathered to provide an additional layer of insider commentary filmed in real time to shed light on the genesis, exodus and revelation of what Director Greaves may or may not have had in mind as he let this concept swirl around in his consciousness for an indeterminate amount of time before finally deciding on how and when and where he would film (from a variety of angles and authorial perspectives) a role play exercise of the incendiary dialogue and deep-seated psychosexual marital conflict portrayed on screen by a pair of relatively anonymous and low-budget professional actors, after allowing us the privilege of seeing others take on the same parts, achieving significantly less memorable results.

Except that, bumbling semi-amateurs though they may be, those discarded bit players also stand on equal footing with the supposed leads of this acutely self-aware process, captured for posterity on 16mm celluloid, infused with Greaves’ anti-hierarchical imperatives and an inherent bias that favors viewers who feel sufficiently autonomous to ascribe their own meaning and value to the experience his film provides, regardless of how it registers with popular opinion, whether taken to heart or instantly forgotten or simply buried in the memory right next to another hundred thousand or so similarly hazily recollected encounters with sub-filtered reality, conclusively accompanied by Victor, a rambling, ranting, semi-coherent street vagabond and self-styled artiste-philosopher who quite pointedly enjoys the last word in this film, despite his seemingly incongruous, off-topic but subversively apropos commentary on vaster and deeper aspects of human social existence than the casual observer would have ever expected to surface at the end of this relatively brief and fast-moving indulgence in experimental art house whimsy.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

Let’s just tell it like it is. This wasn’t a film intended for or even significantly offered up for audiences of 1968. It was merely a seed that was planted in the summertime of that fateful year, destined to gestate, take root and eventually bloom a few decades later, when it was re-discovered, championed and publicized by Stephen Soderbergh and a few other lesser known aficionados in the mid-2000s who were quite understandably entranced by the haphazard audacity of this fearless creative collective, utterly indifferent to commercial considerations and seemingly not all that much concerned at all about whether or not the concepts that informed their efforts would even manage to connect with audiences that had not fully accompanied them down the rabbit hole of reflexive contemplation that would prepare them to engage with this film about the filming of a film being filmed. Watching it now, either on the Criterion Collection DVD or on the FilmStruck streaming service, we see that the copyright notice at the end of the film reads 1971, so for all I know, we’re not even watching the original cut, but from what I can tell, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One was put together to some extent in 1968 and was made available in subsequent years to denizens of the cinematic underground who enjoyed the right connections and were sufficiently hip enough to dig what Greaves and Company were putting down in that era of worldwide cultural revolution.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One is without any argument or apology on my part one of my very favorite releases from the Criterion Collection, simply due to its willingness to plunge ever so deeply into the realms of phenomenological artistic endeavors. Ever since my teenage years, I have been vulnerable to the grip of just about any creative expression that is able to boldly, successfully draw attention to itself as an artifact descended from the mind of some who can’t quite escape from an awareness of the process that he or she is engaged in to bring it into the awareness of other people. I know that this review risks collapsing into a long rambling word salad of dependent clauses that endlessly fold in on themselves, as I struggle to summarize the film at hand as I write this evening, but this is the kind of movie that seems to allow for, if not exactly demand, such an approach, unfettered by any sense of discipline or discretion on my part. I still haven’t really done all that much reading up on Bill Greaves, what he did with his career or even what propelled him to use up whatever resources he could muster in order to create this amorphous blob of a movie. Nor have I watched Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take 2 1/2, the 2oo3 revisit that Soderbergh, Steve Buscemi and Greaves collaborated on that presumably led to Criterion’s decision to release this thing on disc. a few years later. I suppose that this was a classic case of “you had to be there” in order to even approach that level of understanding why he did what he did. But even those who were there seem to have been left behind in his dust to some extent – whether crew or actors or mere hangers on. Nobody exactly had a laser-beam precise read on what Greaves was up to, and I don’t think he even had a clear outcome in mind himself. He was just aware of his own reflection in the mirror, and he kind of got off on seeing what happened when we look at ourselves when we stand in between two reflective surfaces, and what other people see when they see someone standing in the middle of refracting planes, and what kind of reaction one can generate when one has the freedom and the exhilarating recklessness to push all sorts of impolite buttons in order to get a rise out of people, without making them sit around and wait too long to get to the payoff.

Are there ideas to engage with here? Is there a statement made for us to reckon with? Perhaps, probably, I suppose so, sure. Somewhere in the anguish of a deeply jaded, chronically incompatible couple on the verge of divorce and/or psychological abuse, and the drunken verbal hash spewed by the watercolor painter springing forth from the bush territory of Central Park, there is something of substance that I could slow down, back up and analyze here. And in the overly analytical disclaimers of a film crew allowed to go adrift, forced to disavow any perceived intentions on their part of “raping the director,” we’re given a mini-portrait of working class creative underlings left to their own devices, torn between their duties to respect the vision of the auteur and their anxieties about just what kind of a bullshit enterprise they’ve been roped into anyway. I figure a lot of us can relate to that, whatever our chosen profession might be. So in that sense, yes. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm is life.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

Previously: Samaritan Zatoichi

Next: Criterion Shorts of 1968 (Les Blank, Chantal Akerman, Hollis Frampton… And More!)

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)