By 1978, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind had grossed upwards of nearly a billion dollars at the box office, rewriting the cultural landscape and defining the modern blockbuster as we know it. By 1979 he was given carte blanche to direct anything he desired and what he came up with turned out to be the first dark spot of his career, a modest financial success that by no means equaled the gargantuan influence of his earlier triumphs but nevertheless earned a critical drubbing that till this day has solidified its reputation as Spielberg’s greatest and earliest failure. 1941 is a gigantic comedy spectacular that is the epitome of the unprecedented creative control and wildly self-indulgent excess that characterized the American cinema towards the end of the New Hollywood era in the late 70s and early 80s, but it also happens to be an unfairly maligned and misunderstood gem in the career of one of the most successful filmmakers of all time.

Set days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 1941—originally titled “The Night the Japs Attacked”—was written by a young Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, and was incubated by the infamous writer/director John Milius who produced the film after he saw potential in the two Bobs who had just graduated from USC film school. The writing team jammed the screenplay with as much historical kitsch they could dig up, spending hours at the Los Angeles Public Library for research. With the adage “Truth is stranger than fiction” in mind the two attempted to chronicle the mounting hysteria about the inevitable war by basing the madcap action around actual events that included the Great Los Angeles Air Raid of 1942, where a false alarm attack resulted in a blackout and an anti-aircraft bombardment fired above LA, the 1942 shelling of an oil refinery along the Santa Barbara coast by a Japanese submarine, and the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943 between US Marines and Latino teens in California. Eventually the project was given to Spielberg who, after the success of Jaws and Close Encounters, admittedly had nothing on his plate but found himself with the power and money to do anything.

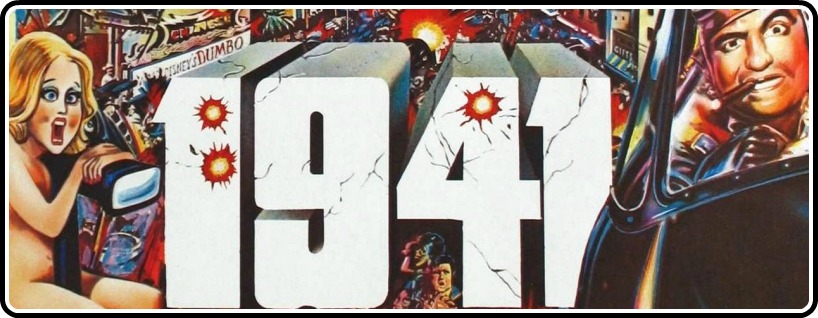

Spielberg would populate his film with a murderer’s row of comedic and dramatic stars alike including Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, John Candy, Ned Beatty, Slim Pickens, Murray Hamilton, Eddie Deezen, Tim Matheson, Robert Stack, Warren Oates, Treat Williams, Nancy Allen, Joe Flaherty, Elisha Cook Jr., Lionel Stander, Christopher Lee, and last but not least Toshiro Mifune in one of his few appearances in an American film. Spielberg’s mantra seemed to be bigger is better, saying that he directed the film “as if it were a demolition derby,” stuffing the picture with intricate special effects, explosions, and wall-to-wall gags that, to critics and audiences at the time, seemed to be more important than an actual plot. One of the film’s posters promises “Soon the screen will be bombarded by the most explosive barrage of [expletive Japanese characters] ever filmed,” critic Michael Sragow’s review for the film in the LA Herald Examiner said watching it is “like being stuck in a pinball machine for two hours,” while David Ansen in Newsweek called it a “Mad Magazine comic-book fresco.” It seemed to be fundamentally packed with just about everything with no clear idea of what these big moments meant to the plot, but where viewers saw an overblown mess I see a much more intelligent and justifiable film whose enormous mindset uses its historical base and Spielberg’s admiring sense of slapstick to new heights.

The film ostensibly foregoes a straightforward narrative, instead choosing to use its dozens of archetypal characters to weave in and out of its screwball tapestry and serve the greater hilarity of the story instead of resonating on an individual level. These are people we don’t necessarily have to explicitly identify with but rather understand as sentimental yet comedic representations of WWII-period forms. In his review in New York Magazine, David Denby said the film “takes a fondly appreciative attitude toward the innocent righteousness of the time,” which is true of any solemn Spielberg film regarding World War II, yet here Spielberg’s comedic angle is used to pointedly suggest the inherent ridiculousness and absurdity of war via a heightened historicism. Zemeckis himself said, “This is a picture that could only be conceived, written, and made by guys who know World War II by seeing it in the movies,” and Spielberg admitted that the film “wanted to be bigger than the war. Bigger than history.”

Its political incorrectness, however, may have been unappealing to viewers who took it to be making fun of a very real and very serious situation. One notorious story from the making of the film involves John Wayne, who the director originally tapped to play the real-life character General Joseph Stilwell eventually played by Robert Stack, calling Spielberg up after he had read the screenplay and protesting that it was Anti-American while urging the young director to abandon the project altogether. This is where the film shares a similar approach to something like Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 classic Dr. Strangelove—a film directly referenced in 1941 by the casting of Slim Pickens who here also reenacts the counting-off scene from Strangelove—in that both films base their broad and ridiculous comedy on humorless true-to-life circumstances, yet Spielberg decides to stay broad with his craziness which doesn’t cut with the same effective satire as Kubrick’s film. But Spielberg, Zemeckis, Gale, and Milus’ efforts to remain as socially—and comedically—irresponsible as possible with the film proves it to be an imaginative lampooning of the speculative hysteria following those very real attacks on Pearl Harbor. One of the film’s taglines, “Paranoia breeds pandemonium,” is perhaps a great little thesis statement for the film in its attempt to be a spectacle writ large predicated on a barrage of insane set pieces and visual gags that never cease but whose keen sense of nostalgia is always basically dependent on a heightened understanding of actual events.

The main set piece gags that viewers found tedious are actually some of the most visionary and innovative of the time, definitely earning the film’s Best Visual Effects Academy Award nomination in scenes that range from a tank rampaging through downtown LA (and even through a paint factory to zany, Technicolor results), the fake air raid on LA that utilizes some of the most gorgeous miniature work I have ever seen, an actual entire house falling off the side of a cliff, and a runaway Ferris wheel that is let loose spinning down an amusement park pier. Another sequence of note, whose brilliance relies on superb staging as opposed to big special effects, is an extended dance number that devolves into a riot between Treat Williams’ irate army grunt and Bobby DiCicco’s immature teen-in-love battling for the hand of Diane Kay’s hapless damsel in distress that is the perfect example of the film’s expertly choreographed madness. Much of the madcap fun—no doubt from Spielberg’s endlessly childlike imagination—amounts to something like a living cartoon where anything is possible. Such an interpretation is evident if not obvious in that Spielberg consulted with Looney Tunes mastermind Chuck Jones on some of the sequences, or just that most of the advertisements for the film are wacky cartoon caricatures of Aykroyd and Belushi hamming up the ironic propaganda of the film’s various taglines.

Though Spielberg himself has stated to biographer Richard Schickel that “What killed the comedy was the amount of destruction, and the sheer noise level,” it was perhaps the audience’s reluctance to accept the classical and modest comedic intention of taking the slapstick that they had basically only seen in the small silent films of Lloyd, Keaton, or Chaplin now blown up to a gargantuan and epic scale that sank the picture. Despite the fact that this sort of comedy had fallen out of favor by the late 70s and was replaced by a more glib stand-up comedian-type, Spielberg’s efforts to appropriate that otherwise outdated mode and his casting of the one person who seemed like the contemporary approximation of those pratfall-based stars in John Belushi work in context for the film’s overall comedic value. It is—plain and simple—hilarious, and the fact that the scale of the comedy is so large doesn’t take away from the essential fun that is mixed in with the spectacle imbued by the director’s talents.

1941 is a movie that is made up of exclamation points and capital letters that many people will understandably find exhausting, but for those who hold on for the ride it follows in a long tradition of big and crazy comedies such as It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World (which was recently hinted at in a Criterion wacky drawing). The Criterion Collection may never get its hands on 1941, either because they don’t think it’s a particularly good film or because Spielberg films will never be licensed out to secondary distributors, but in a world where we get Blu-ray editions and restorations of countless misunderstood films it’s a small travesty that 1941 isn’t available for people to rediscover and reevaluate. Because it became the director’s first major flop doesn’t mean we should judge it too harshly, after all some critics were eager to skewer Spielberg after his two major hits and unloaded on the unsuspecting comedy with sardonic delight. Despite giving 1941 a positive review, Pauline Kael apparently told Spielberg, “You’re not going to get off easy. We’re waiting for you to fail.” But now that time has past and Spielberg went on to bigger and better things—the next thing he did was a little film called Raiders of the Lost Ark—it’s time to look at 1941 with news eyes as a hugely clever and massively hilarious film.

I discovered 1941 years ago, when I was in my early teens, and it became a favorite of mine even before I could recognize and understand all the in-jokes and references. Now that I do, I find the movie even more entertaining. (And also having seen It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, I can also see the similarities between the two films.) Pity more people don’t. I mean, Clue, an initial flop at the box office, has finally gotten the recognition it deserves and is now a cult classic. Why not 1941?

There you go. I always loved – well, maybe not loved, but “had enormous affection for” – the film – I saw it by myself as a 19 year old in a pretty empty cinema. I think it was partly the sound track, but the film actually excited me – left me on a bit of a high as a result of how much I loved the orchestration and build up of one stupid destructive scene after another. (And no, modern films which are wall to wall destruction – like a Transformers movie – just don’t it for me, largely because you just know now that you are watching digital effects, not a full scale thing or a delightfully detailed miniature being demolished.)

Thinking about the film and its soundtrack later (and maybe I read this in a review too – I am not sure) but the John Williams score is really an obvious musical metaphor for the build up to, and release of, an orgasm, which is entirely appropriate given the airborne goings during the climatic part of the film. If this has never occurred to you before, listen to the 1941 March again.

The dance hall scenes were simply spectacular choreography; much of the humour was pleasingly eccentric (John Belushi never actually swallowing a drink, for example); and there was sort of a child like glee to the whole enterprise. I thought it was actually Kael who said it was like putting your head inside a pinball machine, but I stand corrected. In any event, I was happy to see she reviewed it pretty favourably compared to most critics. (I actually wanted to see Lone Ranger because I got the sense that it might the 1941 of today, with many complaints simply about the scale of the thing. But it came and went too quickly and I missed it.)

So yes, I am happy to see this revisionist take on the film too.