David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

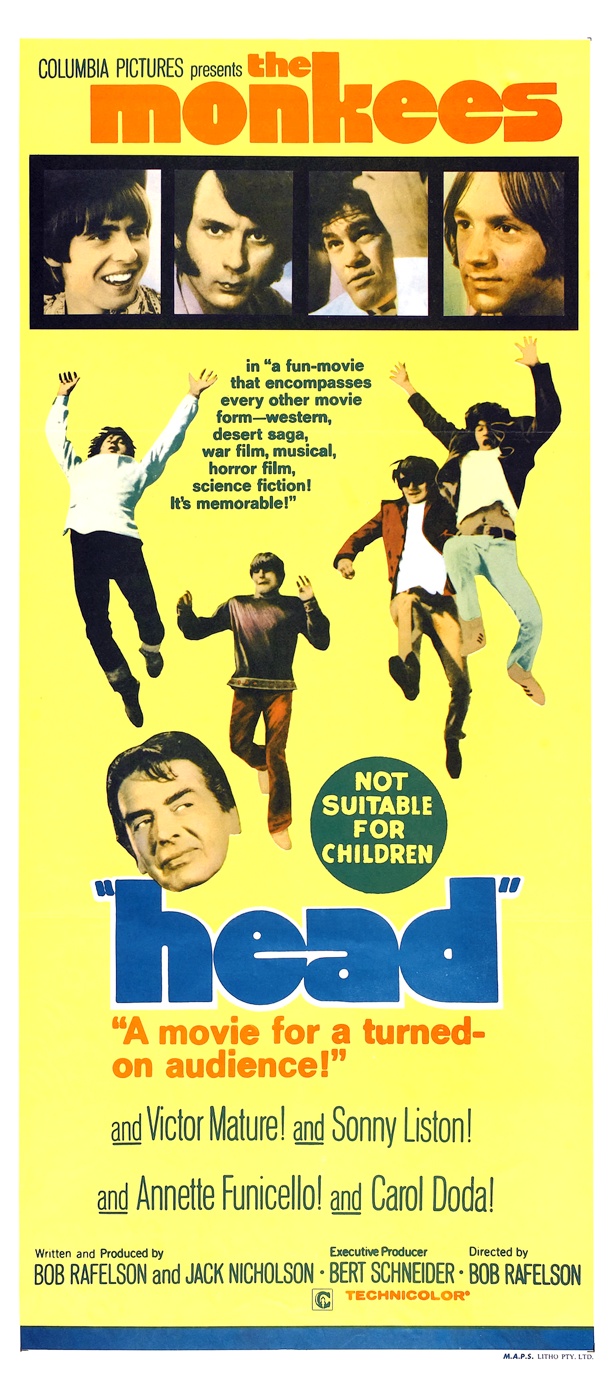

Head is a 90 minute psychedelic film festival, an anthology of trippy surrealistic sketches featuring the Monkees in what was anticipated to be a career-ending blaze of whimsical, anarchic glory. Their TV show had just been canceled, the boys in the band were ready to move on to other things, and the programmers behind the group put all their chips on the table in pulling this movie together. Director Bob Rafelson wasn’t sure what, if anything, he would do again in showbiz, so he went for broke, concocting a frenetic, seemingly random romp through a half-century’s worth of Hollywood cliches, loaded up with wacky cameos, narrative non-sequiturs aimed at amusing an audience of culturally hip stoners and a generous sampling of catchy tunes that nicely cover the pop music spectrum of its time.

Some first-time viewers will instantly love it, but Head might come across as a self-indulgent trifle to others. To that latter group, I encourage a closer look, with an intention to dig beneath the cartoonish surface. There’s a lot being said here, with a sharper and more subversively satirical edge than initially meets the easily distracted eye. Much of the credit for that goes to Jack Nicholson, still all but unknown at that time. He appears briefly in the film, but his main contribution was as screenwriter. This film kicks off the America Lost and Found: The BBS Story box set with a reckless flying leap, seemingly suicidal but actually packed with intelligent purpose and rich vitality. The film played an important role in the emergence of the New Hollywood and holds its own today even without the benefit of a nostalgic fondness for fans who remember the Monkees from their youth.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

In its time, Head proved to be an awkward misfit, failing to generate much interest amongst the critical and counter-cultural intelligentsia due to the involvement of a discredited prefab musical combo they condescendingly regarded as talentless sellouts with nothing worthwhile to say. In commercial terms, The Monkees enjoyed a spectacular run atop the radio charts in 1966-67, but their lightweight stature as bubblegum teen idols fared poorly when placed alongside their musical peers of the era. The reality was undeniable – they truly were a manufactured showbiz phenomenon, not than a “real band” that wrote and played its own tunes. The Monkees’s canned, homogenized origins and frequent appearance on the covers of Tiger Beat magazines generated a scornful bias that would take another decade or more to overcome. Contemporary listeners needed time to mature to the point where they could look past the image and appreciate the slick production and energetic pop song craft. That prejudicial attitude and a hare-brained “underground” marketing scheme that concealed the group’s involvement limited Head‘s initial exposure to many who might have dug it more than they were initially willing to admit.

On the other hand, the inclusion of a few bits of graphic violence – in particular, the Pulitzer Prize winning footage of a Viet Cong prisoner executed in the streets of Saigon also featured in Nagisa Oshima’s Three Resurrected Drunkards – made it too emotionally intense for the teenage girls who took the band seriously. And the overall self-deprecating sabotage strategy of teenybop rockers who are clearly sick of their own media strategy added an extra layer of confusion about whatever it was that Head was trying to achieve.

So the short answer to the question “How does Head speak t0 1968?” is that by all accounts, it really didn’t. It was a big flop that seriously put the future Hollywood prospects of its creators in jeopardy. Even though the film is loaded with all kinds of wonderful oddball bits that make it a fantastic relic of its era, it slipped past in the flotsam of 1968 and for awhile, everybody involved in attempting to give Head to a global audience joined those viewers that the movie failed to connect with in getting busy and moving on to other, more immediately compelling things.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Of course, it didn’t take too long after that for Head to draw more attention to itself. Once Jack Nicholson had emerged as a genuine star, his early efforts got noticed (I already discussed his involvement in the Monte Hellman westerns The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind over on my old site.) A little time and distance and the first glimmerings of nostalgia for the pre-Altamont Sixties era generated a cult following of folks who could sit back and laugh and remember the trippy hijinx of a more innocent time. That’s how I first heard about Head. I was a fifteen year old kid, working my first job as a busboy at a restaurant in Emeryville, California back in 1975, when one of my college-age co-workers told me about this far out movie he was going to see at a midnight showing later that evening. I didn’t join him for that outing (he was a little too cool for me to hang out with off the job, and it was past my curfew anyway), but I did manage to take it in sometime in the few years, one of many flicks that I took in under the influence of various intoxicants during the teenage stoner phase of my life. It was bizarre, it was insane and rad and all that stuff, but I can’t say that it left an indelible impression on me either.

However, I find quite a bit to enjoy about it nowadays. The music is the first point of access. The opener is Carole King’s “The Porpoise Song,” an undulating ode to underwater pleasures fitting somewhere on the spectrum that runs from “Yellow Submarine” to “Octopus’s Garden” to “1983 (A Merman I Should Hope to Be).” “Circle Sky” and “Can You Dig It” were each written by individual Monkees (Mike and Peter, respectively). The former is a thrashy, raucous rave-up number that features them playing as an actual band accompanied by a crowd of screaming girls, while the other is a trendy foray into pseudo-mystical exotica, a gauzy euphoric layered-exposure driven phantasmagoria of gyrating belly dancers lasciviously eyeballed by Mickey in a sheikh costume. You can see bits of each of those numbers in the original release trailer embedded above.

And then there’s this charming Davy Jones solo soft-shoe number, choreographed by Toni Basil with some flashy quick-cut editing. It’s not sampled in the trailer, but it might be the most joyfully affecting bit in the whole film, at least at this stage of my life:

I also have to express my admiration for the hyperactive commitment shown by Mickey Dolenz in his slapstick sequences. He throws his entire body (scrawny as it was) into several scenes that require him to tantrum, tumble and mug shamelessly for comic effect. I get the feeling that this all came pretty natural to him, and was a big part of the attraction he had to his fan base back in those days.

* * *

OK, I’m going to take an abrupt detour from my review of Head right now and jump off in a different direction than readers might expect. Which is perfectly in keeping with the spirit of the film being discussed at the moment. What’s posted above captures what I had written about this movie up until the early part of October, before I took a self-imposed sabbatical from blogging and podcasting due to the compound distractions of the Major League Baseball playoffs and the escalating tension of the 2016 presidential campaign. I found myself incapable of sustained focus on cinema while the outcomes of those two other competitions was still unresolved. Of course, all that suspense is behind us now. I’m glad that the Chicago Cubs won the World Series. I’m considerably less enthusiastic about the election of Donald J. Trump as our new chief executive. It’s the political angle that I want to reflect on here. (And I will bring this ramble back to some thoughts on Head, so hang in there with me.)

After the shock of the campaign’s surprising outcome had settled in enough for me to accept it as a real indicator of the world I live in (and not merely some manifestation of an unimaginable waking nightmare), I began the long slow process of extracting a measure of meaningful insight about what the results signified, and how I would go about functioning in this new era. I’m working out many of these thoughts in a Facebook group I created, called Living in Trump-topia, which politically engaged readers here are invited to join (upon request; it’s a closed group, and I’m currently the only moderator.) It’s a diverse group, with pro- and anti-Trumpers and people in between all represented in an effort to carry on with respectful dialog. So far, I’ve been pleased with the level of discourse.

But this development also got me thinking about the purpose and energy I have been putting into my blogging and podcasting hobbies over the past eight years. In considering this matter, it occurred to me that I started my chronological series in January 2009, just a few weeks before Barack Obama took office. My career as an amateur film critic has taken place in the context of his administration’s cultural and political influence, under federal governance that to me felt like it was leading our society in a positive direction overall. Despite the numerous controversies and tragedies that took place throughout the Obama years, it’s felt pretty comfortable and benign, especially in light of the present uncertainty over incipient fascism or, at the very least, a regime that appears to be intent on exploiting and intensifying the fissures and fault lines that divide people against each other.

Now, with Trump and his cohorts about to take over, there’s a lot of anxiety and dread about what kind of climate we’re heading into. (And I mean climate in every sense of the word.) The alarm that I know is felt by many others besides me has probably led many of us to rethink our priorites: how we spend our time, the causes for which we expend our resources, the messages we express to our contemporary audience and even to anyone who might chance upon our work in the future.

So with all that on my mind, I acknowledge that I’ve gone through a stretch of “why bother?” thinking in regard to the amount of time I spend watching, thinking, writing and talking about movies. In a historic moment where it appears that basic civil liberties that we often take for granted are now at risk, am I really justified in devoting so much energy to creating web content focusing on films from decades long past?

There are several answers to that question that I can choose from. One would be to say, no, I’ve had a good run but I need to give up this endless pursuit so that I can get more involved in direct, concrete actions that effect people in my local and regional communities. I must be ready to align myself with larger scale resistance efforts as well, especially if the darker, more dreadful persecutorial shit really hits the fan. I can’t allow myself to be a passive armchair spectator if the social fabric in this country begins to shred and deteriorate to the point that innocent lives are adversely affected.

The day may come when that answer may present itself as the urgently necessary choice. I pray that it never will, because I do want to continue the long term project of working my way through film history as guided by the brilliant curators working under the banner of the Criterion Collection. I’ve come to love their work, and the community of like-minded cinephiles who for various reasons share my preoccupation with that library of important classic and contemporary films. Beyond that, I do believe in the power of art, not simply as a source of sensual delight and intellectual stimulation, but as a means of finding inspiration, resolve and clarity of insight when life forces us to look at dimensions of experience that we’d rather avoid, deny or simply allow to defeat us.

One of the unifying themes that the Criterion films share (along with the diverse global community of fans that I’ve connected with through our shared fandom) is the perennial quest for enlightenment, liberation and community in a world where such ideals are often mocked and trampled upon by those in positions of power and privilege. That universal quest can be portrayed as comedy or as tragedy, as subdued meditation or as raging howls of protest. The characters can be drawn from the annals of history, from the archetypes of immortal mythologies, or drawn from the contemporary experiences of our peers, whether they be found among the anonymous masses or are named as the most famous personalities of their times. It’s that vast spectrum, the endless variety of women and men from all stations of life, in cultures ancient, modern and futuristic, that I find represented in the Collection. I believe these wonderful cinematic treatures have a lot to teach us in our personal and collective, always-ever-shifting here and now.

So this is the perspective I’m going to strive for in my future contributions to this website, whether through text or the recorded sound of my voice, and anywhere else that I might be invited to offer an observation or two on the art of film. I’m going to keep an eye on what’s going on in my world, in our world, and see what kind of connections and commentaries are brought to mind as I continue to wend my way through some incredible movies of the late 60s and (soon enough) early 70s. Yes, I will get there, as long as strength and breath endures in my body! :)

That’s probably enough editorializing along that line for now. Back to Head – how does it speak to our current dilemma?

We can start with the underlying grim realities of 1968, the year this film was released: th Vietnam War, already mentioned several paragraphs ago, was at its peak. Many young men of the same age or even younger than the Monkees were being killed, maimed or psychologically scarred in the battlefields of southeast Asia, and of course the people who lived there were suffereing even greater traumas. The litany of riots, assassinations and hostile tensions between races and generations that ran rampant throughout that year has been recited by many authorities who approach that history from different ideological angles. It was a rought, nasty year in so many respects, and as big of a bummer as 2016 has been in many ways, I can’t say that it has come anywhere close to matching 1968 in terms of sheer tumult and global upheaval. But all bets are off for 2017 in that regard! There are many fuses lit and sparking in hot spots around the globe right now, and who knows which of them will finally blow up?

But I take encouragement from Head: the boisterous energy of smart young men (those on camera and those behind the scenes) who took advantage of the opportunities placed before them to craft a media artifact that exposes and lampoons the hypocrisies of the entertainment industry and its relentless effort to shape our consciousness through advertising, narrative conventions, the amplification of hype, a naive misplaced faith in technological advancement, the commodification of desire and the cultural stereotypes that, noxious and obscuring as they often are, also provide a sense of bearings as we seek to locate our current position in the vast socio-cultural matrix that we all inhabit.

Go ahead, pick the Monkee who best fits your personality profile. Join him on his journey and see where it leads you. Head is really a mini-universe of its own, a microcosm that loops around on itself, bookended by apparent acts of suicide, a temporary defiance of the gravitational norms that bind us all, unexpectedly leading to an underwater wonderland of exquisite beauty, a floating sensation where we’re guided out of our disoriented freefall by gorgeous mermaids undulating in synchrony with dreamy theme music to complete the cycle.

In between the plunges fore and aft, we will dance, fight, shoot, run, sing, cry, shout, make love, get knocked down, get sucked up, stroll through flower strewn fields,stagger across arid desert wastelands, converse with swamis, get harassed by cops, behold startling terrifying visions, offer solace to freaked-out friends, run for our lives from ghastly mocking giants and listen to the futile babblings of overly opinionated elders who strive to pass their prejudice and repression to the young generation.

Eventually we discover that we’re all just playing parts scripted for us by faces and forces both closer and more distant than we ever realized. We’ll see things that don’t make sense, force connections that ought not fit, but do anyway, and discern patterns and truth where at first we could only see chaos and nonsense. Head starts with screeching feedback, soars through time and space, boxes us back up in an oversize aquarium when the visual journey reaches its conclusion and ends with jumbled credits and an anonymous giggle. Somewhere buried deep within the tumult, or maybe even bobbing up on the surface, there’s a message worth extracting: keep pushing for freedom. Kick your way through the fake scenery, recognize the game that’s being played, inhabit your role with zealous enthusiasm and don’t let the limitations of your script strip you of life’s joy. Head was then, and can be now, a bracing jolt of playful cosmic awareness capable of guiding transitioning souls through difficult times.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Battleship Pretension (Scott Nye)

- Cinepassion

- Dangerous Minds

- Fanboy Nation

- Ferdy on Films

- The Guardian

- Hollywood Reporter

- New York Times (1968)

- Roger Ebert (1971)

- Shock Cinema (1989)

- The B-Movie Catechism

- The BlueMahler

- Through the Shattered Lens

- Ultimate Classic Rock

Previously: Beyond the Law

Next: The Living Skeleton