David’s Quick Take for the TL;DR Media Consumer:

Shame is Ingmar Bergman’s “war movie,” a disclosure that already feels to me like I said too much, since I went into this one knowing next to nothing about it and was therefore all the more pleasantly stunned and staggered by the discovery. So if you haven’t yet watched it, stop reading now, and go do so right away, or at least before you proceed much further in reading here. It’s an excellent film and in my opinion, yet another marvelous, essential “must see” entry into Bergman’s canon. (Other critics, and even the director, don’t share my assessment; I’ll address that below.) But for those who’ve seen it, I have to figure they can agree with my surprise at the inclusion of screaming fighter jets, exploding grenades, dead paratroopers hanging from branches, machine gun blasts, interrogation and torture… Not exactly what I’ve come to expect when I sit down to watch a Bergman flick.

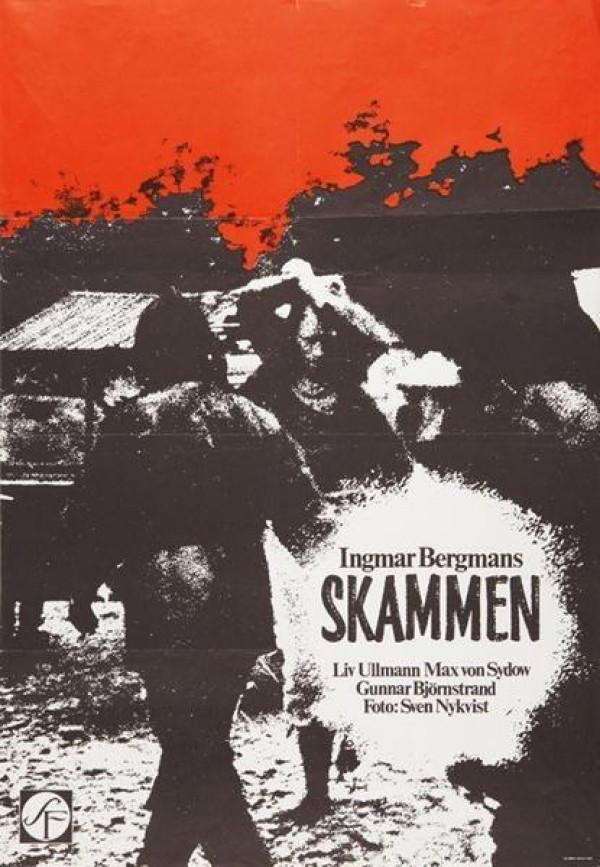

But after that element of surprise wears off, there’s so much more to dig into. Primarily, it’s the expressive character portrayals offered by Liv Ullmann, Max Von Sydow and Gunnar Bjornstrand, who each take us on their respective sojourns down paths of disillusion and betrayal as they see the familiar elements of their comfortable, freely chosen lifestyles stripped away in the chaos of a maddening civil war. Liv and Max are the central couple, enduring the grim standoff of a marriage gone stale due to excessive focus on each other and isolation from the rest of the world, which the husband in particular seems no longer capable of putting up with, as he’s more or less forced his wife to live with him on a rustic island farmstead. The petty bickering of their perpetual dissatisfaction with each other gets put into a humiliating context when they’re caught in the crossfire of rival combatants. Bergman, along with his celebrated d.p. Sven Nykvist, are perfectly positioned to assist the viewer in pondering the psychological and existential depths revealed as we dissect the forlorn couple’s ever-worsening dilemmas.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

Shame was Ingmar Bergman’s second film to be released in 1968, making its premiere in late September after Hour of the Wolf debuted in February of that year. Both films were actually shot in 1967, so going by appearances, it looks like Bergman just finished up the editing on one before moving on to do the post-production on the other. They each tackle very dark themes, and can be said to represent Bergman’s unique explorations of genre cinema, Wolf being his neo-gothic horror film (long the lines of Rosemary’s Baby) to pair up with Shame‘s focus on the tragedy and folly of war. Of course, they’re each unmistakably “Bergmanesque,” by which I mean, almost unrelentingly bleak in their outlook and what life ultimately has in store for the majority of people living at any given time. For that reason, it’s not totally surprising to learn that Shame hasn’t earned the lasting reputation of Persona, from 1966. It can (and probably is) considered by some to be evidence of a decline after the peak of his cultural influence of the early 1960s, and I think it’s significant that the Criterion Collection had overlooked both of his 1968 offerings up until last month, when the FilmStruck streaming service included this film in its online library. (Which is why I’m reviewing it here.)

The film opens, during the credit sequence (customary austere white text on black background) with a musique concrète sound collage that could have been seamlessly inserted into the Beatles’ 1968 landmark recording “Revolution 9” – harsh static, radio clips of an ominous political significance, portents of meaning found in the inadvertent juxtaposition of spoken words in multiple languages, ending with an enigmatic phrase (in two different voices, both speaking English) that sounds something like “Most of all… in a moment of understanding.”

We’re introduced to Jan and Eva, an artistic reclusive couple, both of whom were orchestral musicians who decided to get back to nature, checking out of the urban rat race, living off the land in a small but largely self-sufficient farm. They’ve been married for seven years, but haven’t produced any children. Their chosen way of life has made them poor, and Jan’s refined skill set doesn’t really include much along the line of maintenance/repair abilities, creating a host of petty disputes for the pair to work around. Whatever purpose was supposed to be accomplished by this experiment in alternative living now seems faded and forgotten. Their anguish at the seeming dead end they’ve landed in is palpable, and they find themselves unable to escape neither the chaotic disruption of political warfare that engulfs their island retreat nor the soul-crushing tedium of their isolated absorption into a dysfunctional dyad.

Even so, Jan and Eva do enjoy brief flickers of renewal over the first half of the film. We see Jan’s erotic arousal via jealousy of seeing his wife interacting with another man, a fisherman named Filip who will reappear in other, more ominous roles as the story progresses. Likewise, Eva occasionally rediscovers whatever it was that initially drew her to the side of this idealistic, insecure dreamer, lighting up the screen with her delightful, clear-eyed smile and offering an affectionate embrace to repair the damage of careless harsh words delivered in moments of frustration.

Once the war breaks out, the trials they’re subjected to place excruciating strain on their already fractured relationship, leaving us in the audience to contemplate how well we might stand up under such pressures. In 1968, the Vietnam War weighed heavily on the minds of the kind of people who would be drawn to watch an Ingmar Bergman film, and the director himself felt some sense of obligation to address the current events. In his 1990 biography Images: My Life in Film, he writes:

To tell the truth, I was exorbitantly proud of this film. I also felt I had made a contribution to the current social debate (the Vietnam war). I convinced myself that Shame was welll made. I had suffered under the same delusion after finishing A Ship Bound for India. And the same thing would happen to me again later when making The Serpent’s Egg…

When I made Shame, I felt an intense desire to expose the violence of war without restraint. But my intentions and wishes were greater than my abilities. I did not understand that a modern portrayer of war needs a totally different fortitude and professional precision than what I could provide.

Once the outer violence stops and the inner violence begins, Shame becomes a good film. When society can no longer function, the main characters lose their frame of reference. Their social relations cease. The people crumble. The weak man becomes ruthless. The woman, who had been the stronger, falls apart. Everything slips away into a dream play that ends on board the refugee boat. Everything is shown in pictures, as in a nightmare…

Bergman goes on from there to proclaim his penance for mistakes he considers himself to have made in not picking up on some of the flaws that he now perceives in this film, which didn’t even merit a single mention in his earlier, more narrative autobiography The Magic Lantern, published in 1987. I’ll certainly grant him the right to critique his own work, even though I regret his apparent inability to appreciate the greatness of what he did achieve. I deeply appreciate his total lack of concern with so many of the conventions of our typical war movies – valor on the battlefield, the heroic sacrifice of strong young men on behalf of a noble cause, the bold willingness to confront the forces of evil no matter what the cost, or even the heart-wrenching trust invested by ordinary people on behalf of their cynical manipulative leaders who enlist their tribe’s blood and resources in the pursuit of wicked objectives. Those dimensions of war have been amply chronicled over the years, and I’m glad to have been stirred to my depths on many occasions when such themes have been explored.

What Bergman accomplished here, for which I’m grateful, is the exposure of just how venal and antagonistically reactive ordinary people can and do become when the thin veneer of civilized behavior is no longer considered necessary or expedient in light of present circumstances. In Shame (an emotional sensation that Bergman indirectly attributes to God, the dreamer of “dreams we have to participate in,” but which just as applicably applies to each of us as individuals), Bergman strives to expose the base impulses of lust, power, revenge, hatred and fear that continue to drive so much of our behavior, despite our best efforts to sublimate and regulate all of that energy beneath the facade of cultured and domesticated life. I don’t fault our collective efforts to keep our worst instincts under some measure of control, but I also derive a certain refreshment from a frank acknowledgement that such primitive drives lurk just faintly beneath the surface in so many of our interactions. The layer of protection that safeguards us from each other, and from ourselves, is merely skin-deep. Shame broke through the comforting delusions that wars in Vietnam and elsewhere around the globe in the late 1960s were somehow simply not possible in Europe, North America or other regions currently experiencing domestic tranquility. Bergman reminds us that our very neighbors, or even we ourselves, may be the agents of terrifying cruelty and barbarism, when we lose our capacity to redirect our passions in order to avoid the sensation that gives his film its title.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

I’ll keep this part brief, since I’ve already expressed quite a bit about what Shame communicates to me in the paragraphs above. With the recent election of Donald Trump, a presidential candidate who embodies numerous authoritarian tendencies, and is widely regarded as the most shameless American politician in recent memory, I watched and rewatched this film as if it might serve as a prophetic oracle of some sort. Bergman never gets into the politics of what made this unnamed Nordic society go to war with itself, and that’s a big part of what makes the film so successful, in my mind anyway. The particular points of conflict, the issues that divide neighbors and citizens against each other, are not very important after one steps back a pace or two to take in the larger situation. Whether we’re residents of Aleppo, Ukraine, the Congo or on one side or the other of the Red-Blue divide in the USA, we’re all at risk of falling into the drifting aimlessness of Shame‘s disturbing finale, even if the topography of our local region makes the analogy more metaphoric than literal in our particular situations.

It’s apparently built into our nature to take sides, to divide along partisan lines, and to perceive within those divisions some larger sense of purpose and duty that will, in many cases, cause us to not only jeopardize our own well-being for the sake of a cause, but also to feel the right to annihilate those who adopt the opposing position. We might consider our role in the larger historical process to be of more lasting significance than our interpersonal commitments. Or we might regard ourselves as apolitical, content (or even morally obliged) to separate ourselves from all the ideological strife and tumult in order to pursue more righteous and edifying goals. Both postures are accompanied by significant risks, with blind spots that lead to complacency, apathy or ill-founded certitude. The net effect that Shame had on me was to stir up anxiety, provoke feelings of dread and (I hope) help me to sharpen my focus in order to detect and address any signs of incipient totalitarianism as our society goes through the upcoming shift in governing authority. Maybe my apprehensions will prove in hindsight to be a bit exaggerated. I won’t take that for granted. I want my future reality to be lived with Shame to the fullest extent possible.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- New York Times (1968)

- Le Mot du Cinephiliaque

- Milk Plus

- Not Coming to a Theater Near You

- Ozu’s World

- Roger Ebert

- The Stop Button

- Thrill Me Softly

Previously: Spirits of the Dead

Next: Faces