David’s Quick Take for the TL;DR Media Consumer:

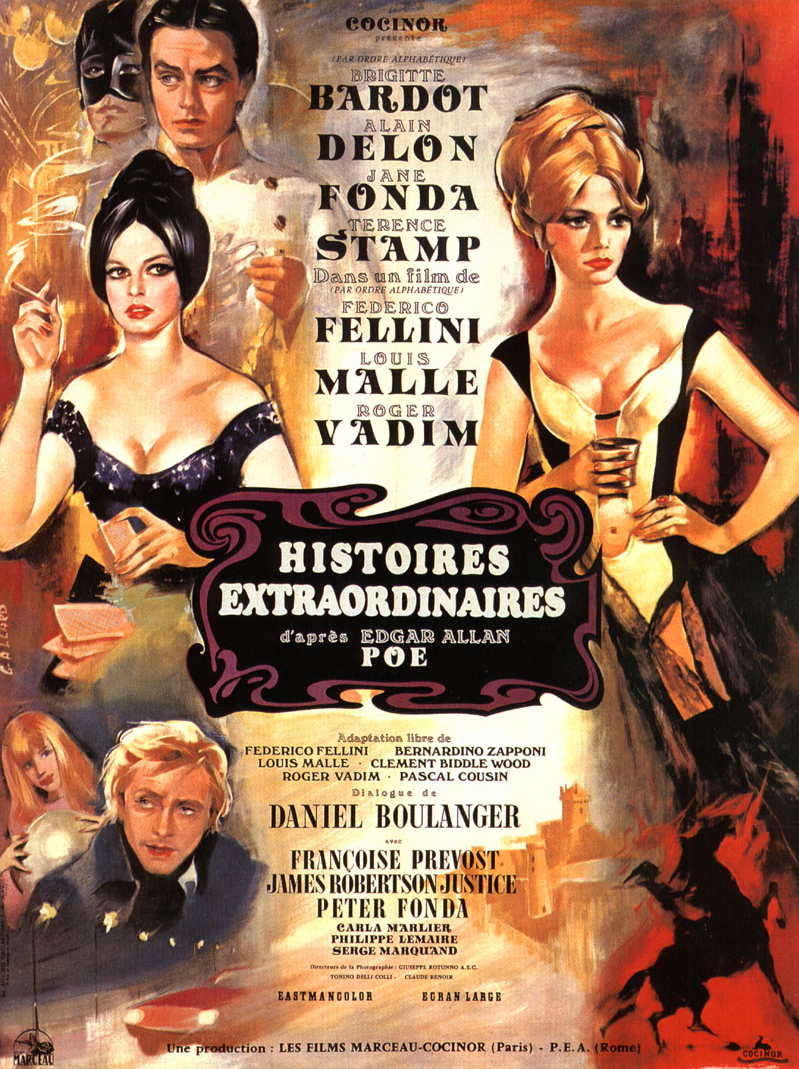

The resume is solid and the references check out: Federico Fellini, Louis Malle, Roger Vadim each shouldering a directorial third of the project, with talented crews working at their behest to create visually elegant environments to support the stories they tell. Top shelf recruits from leading “beautiful people” actors of their generation: Brigitte Bardot. Alain Delon. Jane Fonda. Peter Fonda. And then there’s Terence Stamp, probably less renowned than the preceding quartet, is roguishly seductive as a disheveled blond wastrel with a suicidal bent. Source material drawn and freely adapted from short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. Ray Charles contributes to the soundtrack. A goosebump inducing first person POV midnight dash through the streets and alleyways of Rome in a vintage 1964 Ferrari LMB Fantuzzi just adds extra sprinkles on top. Though the overall impact of the film makes it feel like a minor but fun diversion, Spirits of the Dead is a wonderful discovery that I would not have made if not for the opportunity presented to me by Criterion’s new FilmStruck streaming service.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

Omnibus films were a thing in art house cinema circles back in the mid-1960s, offering audiences a chance to sample the works of various auteurs in one convenient sitting, while providing those same directors an opportunity to stretch their creative wings without the pressures and logistical challenges of having to shoot a full-scale feature. With all of the attractive and marketable ingredients listed above, it’s not at all surprising that this project got the green light. One of the most interesting aspects of this film is in observing how each director took advantage of the invitation to collaborate.

Roger Vadim, married at the time to Jane Fonda, enlisted his wife to once again star in a sexy genre romp (switching over from Barbarella: Queen of the Galaxy‘s sci-fi to this nominal exercise in horror), apparently utilizing some of those same costumes (or at least, the highly revealing, form-fitting patterns used to create them.) Metzengerstein, a gothic tale of haunted equine revenge, gives Vadim a generous platform to illustrate variations on aristocratic decadence and debauchery that enticingly showcase Jane’s lithe anatomy. Her willingness to play a thoroughly sadistic libertine might surprise viewers who mainly know her from the mainstream Hollywood work she did in subsequent decades. The location shots, in the vicinity of a magnificent old castle on the north coast of France, are shot with lush eloquence by Claude Renoir (Jean’s nephew), and a few scenes of Jane frolicking on horseback across an isolated coastal landscape are reminiscent of what Caleb Deschanel accomplished a decade later in the earlier portions of The Black Stallion (though here with exponentially sexier results.) These indulgences, along with Poe’s rendering of a male protagonist, were not present in the original short story, so credit goes to Vadim and his screenwriting partner Pascal Cousin for making that crucial innovation, on behalf of what I consider to be much more compelling visual and narrative possibilities.

Louis Malle gets the middle portion of this two hour trilogy, a doppelganger yarn named William Wilson, and by just about all accounts, it’s the least successful of the three installments. I don’t think its all that bad, myself, even though it may feel a little more paint-by-numbers than the shorts that serve as brackets. Alain Delon plays the titular figure, a military officer who manages to outperform the Countess Metzengerstein when it comes to unblinking cold-hearted cruelty inflicted on innocent others. We first meet young Wilson as a child, portrayed by a kid who appears to have had an extraordinary advantage in growing up to be as gorgeous as M. Delon himself. His steely resolve in both the commission of crimes and receiving his punishments is quite unnerving as it demonstrates some fundamental disconnect between the young man’s will and anything resembling a conscience. But we quickly discover that his conscience, once expunged from the child’s mind and soul, seems to have taken on a life of its own, in the person of another individual who goes by the name of William Wilson. Both men prove to be visually indistinguishable from each other, but the more ethically-oriented of the two seems to have a habit of receding into the background up until the moment that the depraved W.W. ascends to the pinnacle of his sins. The incidents pile up on top of each other, escalating from one outrage to the next, until the stage is set for a suitably tense showdown at the card table with a cigarillo-smoking Brigitte Bardot in black wig and equally opaque mascara. The scene is replete with a kinkiness worthy of late Bunuel. From that peak moment, the segment grinds on down to its predictable but nevertheless poetically poignant resolution. This telling is the most faithful to Poe of the three tales told in Spirits of the Dead, which might as well serve as an effective retort to those critics who consider it the least successful. As for Malle, his involvement produced a well-timed payday, as it helped to finance his next feature, the controversial Murmur of the Heart, and bought him a bit of time from more commercial pursuits so that he could head off to southeast Asia to capture the footage that eventually became the documentaries Phantom India and Calcutta (soon to be discussed on an upcoming episode of The Eclipse Viewer podcast.)

Federico Fellini’s Toby Dammit was based on Poe’s story “Never Bet the Devil Your Head,” but it’s more accurate to say that the adaptation emerged from the suggestion of just a few lines from Poe’s manuscript. It’s the only three of the segments set in a contemporary context, the preceding two each filmed as obvious period pieces more suggestive of Poe’s typically timeworn and eldritch atmospheres. This free and loose approach served Fellini very well, as he emerges from this joint effort of Histoires Extraordinaire (the French title) with the film most worthy of standalone and repeat viewing. Toby Dammit functions as a culmination of sorts for what Fellini had been working on up to that point in the decade, going back to his blockbusters La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2, along with his first color production Juliet of the Spirits.

Elements from each of those films can be discerned in this story of an alcoholic British actor, renowned for his Shakespearean work but going through a personal breakdown after an extended period of hedonistic self-indulgence. His anxiety is stirred up by a recognition that the various deceits and flourishes he employed to advance his career, common as they are in the toolbox of most any artist or creative type, are on the verge of being discovered by his admirers. Dammit’s distress is further compounded as he comes to grips with the surfeit of illusions that underwrite his entire industry, leading him to behave recklessly in a futile effort to escape the traps he laid for himself over the course of a career he now sees as riddled with masturbatory self-absorption. Clearly, these are concerns that Fellini brooded over himself even at the height of his success. His genius at transforming such episodes of crippling doubt and self-loathing into piercingly funny scenarios established the manic escapades of La Dolce Vita and the fully realized waking nightmares of 8 1/2 as cinematic milestones. Toby Dammit will never enjoy such an exalted reputation, but it’s absolutely worthy of seeking out for anyone curious to track Fellini’s artistic progress. In his 1969 review for the New York Times, Vincent Canby called it both “marvelous” and “major.” I think it serves as an effective bridge (to which I’ll add, “no pun intended,” for the sake of readers familiar with the short’s grim finale) between Fellini’s artistic peak of the early 1960s and the more wildly flamboyant, excessive and inconsistent carnivals of his later work from 1969’s Satyricon onward. Toby Dammit draws this macabre triptych to a memorable and impressive close, in sync with the spirit of its times with a playful, freewheeling, slightly surrealistic vibe that somewhat incongruously brought to my mind the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, filmed right around this same time.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

As I think I’ve already conveyed, I found Spirits of the Dead highly entertaining and a very welcome gap-filler in my knowledge of the respective directors and actors involved in its creation. I love the brevity of the episodic format. I enjoyed reading the Poe stories (linked below), noting the unique twists that each creative team introduced into their narratives. The sum total of the effort may not have made much of a lasting impact in the annals of film history, and given the abundance of talent involved, that might be regarded as a significant shortcoming in the opinions of some viewers. Even though there is a UK blu-ray available, I don’t think this movie really needs a Criterion upgrade. But there’s plenty to enjoy here. Spirits of the Dead feels like a perfect example of the kind of stuff that FilmStruck can specialize in preserving for the sake of satisfying curiosity in those so affected.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- New York Times (1969)

- Ozu’s World

- Screen Anarchy

- Oh, the Horror!

- Need Coffee

- Infini-Tropolis

- Source Material – Short Stories by Edgar Allan Poe:

A nice fan-made music video featuring footage of Metzengerstein:

Previously: Genocide

Next: Shame