David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

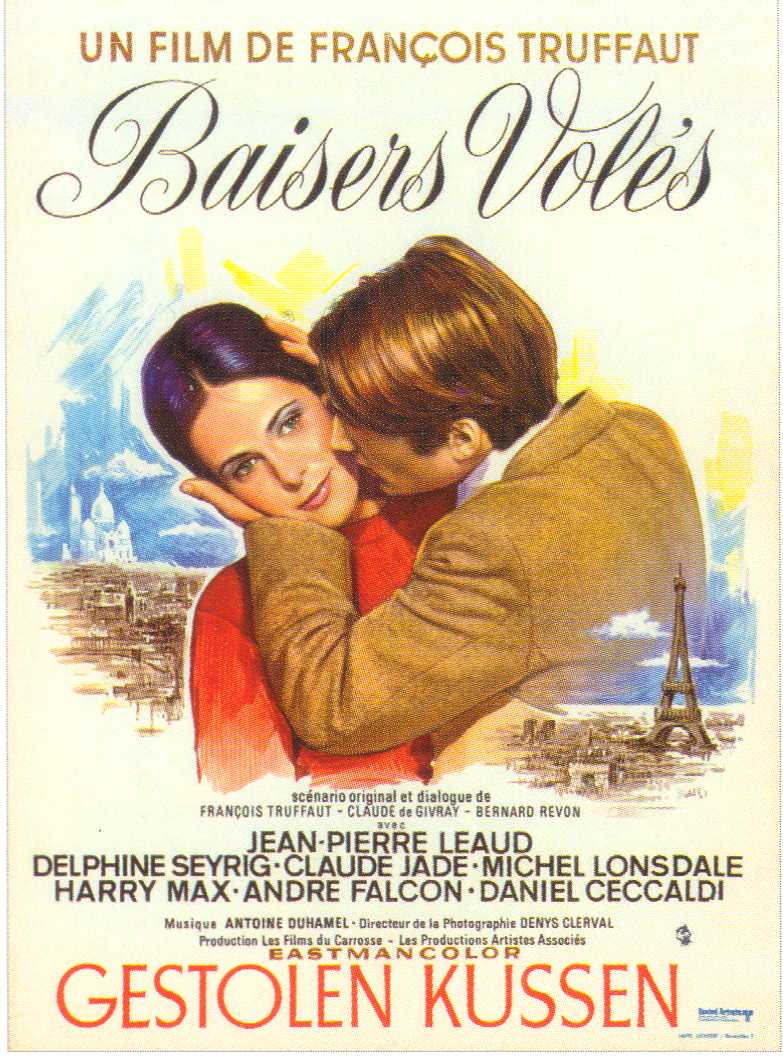

Stolen Kisses was Francois Truffaut’s third exploration of the character Antoine Doinel, to whom we were introduced when he was a child in The 400 Blows and was glimpsed a few years later in a short segment Antoine and Colette that was part of an omnibus film titled Love at 20. Here we see Antoine as a young man, as he stumbles into adulthood working a variety of unskilled entry-level jobs, impulsively falling in love and gliding from one scrape with authority into another as he seeks to find his way through the world. The tone of this film is lighter, more overtly a romantic comedy, and seemingly inconsequential in terms of enduring substance and social commentary when compared to The 400 Blows. It could have been easily plausible to make this same movie with a lead character of a different name, even if Truffaut had still cast Jean-Pierre Leaud as its star performer. Leaud was by now a familiar representative of his emerging generation through his mid-60s work with Jean-Luc Godard, most notably Masculin Feminin, and seemed to have a unique ability to reference the restless, unsettled state of flux so common to people in their early twenties, both then and now.

But of course the continuity of following the history of young Antoine, an iconic face of the Nouvelle Vague, has a lot of appeal. The end result is that Stolen Kisses can easily be enjoyed on its own terms if one should happen to watch it without any awareness that this was the same kid that the rest of us saw romping through Paris and going AWOL from the detention facility nearly a decade earlier. But it does add an extra measure of satisfaction to get an update on that little mischief maker whose fate was so uncertain when he was seen standing on the ocean shore. Francois Truffaut had comfortably settled into the job of creating popular, accessible entertainment, fully informed by the critical sensibilities that had led him to become a director rather than a mere commentator. In Stolen Kisses, he skillfully wove a blend of comedy, romance, even a touch of mystery and suspense in the last third of the film, that earned him an Academy Award nomination and provided plenty of momentum to leave audiences wanting to know more about the further adventures of Antoine Doinel.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

Given the Parisian setting of Stolen Kisses and Francois Truffaut’s known involvement in the tumultuous protests that swept across France in the first half of 1968, I was expecting to see something more politically charged when I first sat down to watch the film. A few important references are made to current events, starting with the opening sequence which is a tribute to Henri Langlois, recently deposed head of the Cinemateque francaise, a martyr for the cause of cinema, we might say. The visuals show the entryway to the Cinemateque, its gates locked and a handwritten “CLOSED” sign in the window. That scene has nothing to do with the rest of the movie, but it’s still important.

The other key bits that locate the film in its unique timeline are a few glances at TV screens mentioning that student demonstrations are going on, events to which Antoine seems all but oblivious, or at the very least, disinterested. I take that level of detachment from the heated controversies of the times as Truffaut’s endorsement of the truth that for a lot of poor and working class people, active engagement in social causes and overt, organized defiance of civil authorities is a form of privilege that they simply don’t have time for or find all that satisfying, since the problems they’re dealing with probably won’t be alleviated even if the revolution should happen to succeed. Antoine is currently being buffeted about by a swirl of confusing emotions and massive uncertainty about what his future holds in store. Assembling in marches and chanting slogans expressing the outrage of the masses would be nothing more than a distraction from the more urgent needs he has to attend to just to stay afloat.

In addition to those obvious nods to current events, Stolen Kisses also ventures into territory similarly explored in 1967’s The Graduate, involving an affair between an older married woman and a bewildered, besotted younger man who can’t say no to her advances even though he recognizes the trouble he’s getting himself into. Both films balance the unsustainable fling with a more conventional romantic interest between lovers of similar age and experience, and they each wind up with the attractive young couple paired up at the end and making their exit from the screen into a future sure to be littered with formidable difficulties but a tinge of hope that things might somehow work out after all.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

It’s taken me a couple weeks or so to figure out what I wanted to write about this film. There are several reasons for that – the recent political conventions and my subsequent absorption with all the analysis of what it all means for our upcoming election and a busy schedule full of summertime activities have distracted me from blogging. Even more than that though, I just didn’t have a whole lot to say about Stolen Kisses. After my first watch, my initial response was that it was a pleasantly entertaining 90 minute diversion, much more of a lightweight offering than I was expecting. That about summed it up. I’m glad that I didn’t just drop a few quick lines to that effect and move on to the next thing, since I’ve enjoyed having various scenes from the film rolling around in my head since then. The trailer above offers a nice refreshing summary of some of those moments, Even without subtitles, it provokes smiles and charming recollections: Antoine’s fearless jaunts through Parisian street traffic, his barely concealed hilarity at the absurd self-seriousness of the adult world at work, his helpless distraction at the sight of a pretty face, his nervous gulp despair when he feels the weight of authority and responsibility pressing down upon him.

And the supporting cast leaves its own splendid impression. Delphine Seyrig as the store owners wife who recognizes Antoine’s enchantment and pursues him for her own satisfaction is perfectly amazing here, as she’s been in the varied roles I’ve seen her take on in films as diverse as Last Year at Marienbad, Muriel or the Time of Return, Who Are You, Polly Magoo, Mr. Freedom, The Milky Way, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and her crowning triumph, Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles. Claude Jade as Christine, Antoine’s more age-appropriate on & off girlfriend, is beautiful and sensitive and a perfect grounding force for Antoine’s mercurial impulses. The older men in the film all play a part in helping to draw tentative boundaries around Antoine, each conveying aspects of their hard-earned experience that in their opinions will help the impetuous fellow understand that he needs to make certain adjustments to fit into whatever role society will eventually press upon him. Of course, Antoine reacts to what they tell him but the viewer is never all that sure about how much is really sinking in, as his frequent furtive glances give the impression that he’s always keeping an eye on the nearest exit.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Criterion Collection

- Criterion Confessions

- Criterion on the Brain

- In the Realm of Cinema

- Le Drugstore 1968

- New York Times review (Vincent Canby, 1969)

- Only the Cinema

- Senses of Cinema

- Spirituality and Practice

Note: The next film on my timeline is Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell. I’ve already reviewed that film in conversation with Trevor Berrett in an episode of The Eclipse Viewer. So I’m not feeling any urgency to watch it again and give it a fresh review here. Instead, I’m moving on to The Immortal Story, a new Criterion release at the time of this writing. Nice timing! Whoops, I changed my mind…

Previously: Zatoichi and the Fugitives