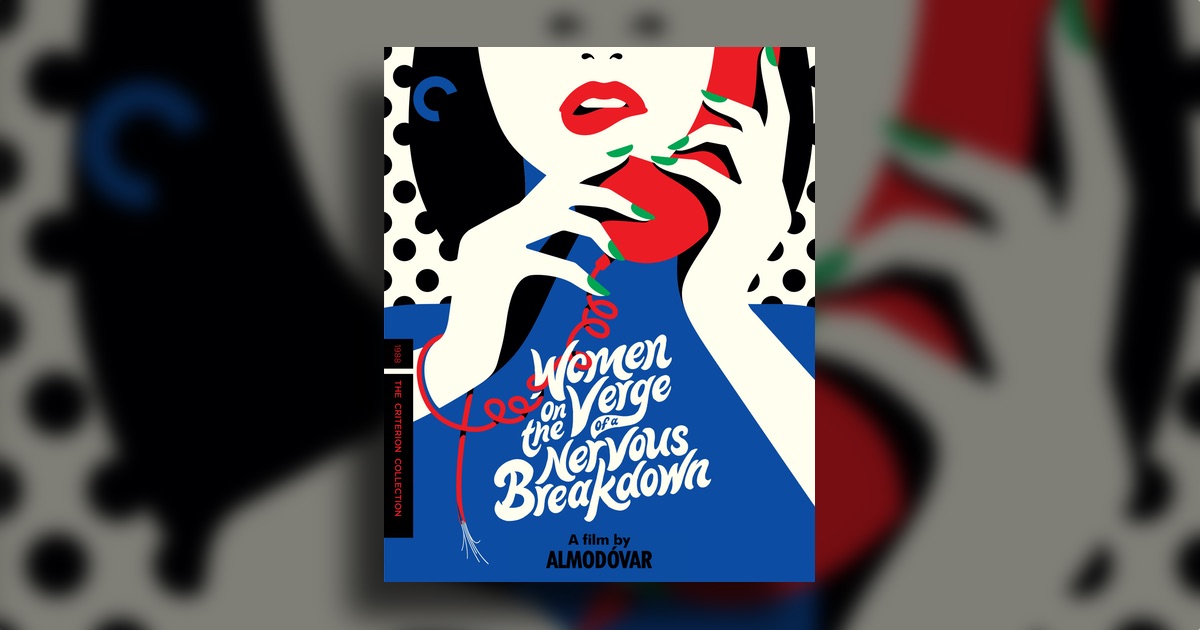

It’s only February, yet The Criterion Collection has already released two exceptional screwball comedies this 2017. The first, His Girl Friday, released last month (and reviewed by David Blakeslee here), is a film that comes to mind whenever the term “screwball comedy” is bandied about. The second is Pedro Almodóvar’s 1988 film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Almodóvar, particularly at this early point in his career, was better known for dark comedies that did all they could to confront and provoke and remind everyone that with the demise of Franco’s regime Almodóvar intended to utilize a newly discovered freedom of expression, so the film’s provenance, combined with the film’s dark premise, means that the delirious, escalating light comedy of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown will come as a surprise (a pleasant surprise, I think) to first-time watchers familiar with the rest of Almodóvar’s work. And I’m willing to bet first-time watchers will look forward to the pleasure of a revisit. It’s a delight.

But let’s start with the dark premise. When he sat down to write the film, Almodóvar was inspired by Jean Cocteau’s single-character tragedy The Human Voice, a dramatic monologue from a woman recently abandoned by her love, in which the steps of her breakdown are dramatized over a series of phone calls. Almodóvar’s title, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, pays homage to the plight of Cocteau’s protagonist, and the starting place is similar: when Almodóvar’s film begins we have another woman trying to call the lover who has abruptly abandoned her. The woman is Pepa, coyly played by the lip-biting Carmen Maura, who had worked with Almodóvar in all but one of his first handful of films. The lover is Iván (Fernando Guillén), an attractive but vacuous, cowardly man whose best quality is his seductive voice. Pepa has been trying to talk to Iván, and her penthouse is suffering from her frustration: she’s burned the bed, she’s thrown the telephone out the closed window (a few times). Iván, though, is avoiding Pepa at all costs, and Pepa might be thinking about ending all with gazpacho spiked to the brim with sleeping pills. Meanwhile, Pepa’s friend Candela (María Barranco) has come to Pepa’s home to hide from the police because she hooked up with a terrorist who told her a bit too much.

However, as serious as these concerns are, and as real as the emotional stress is to the women, the film is consistently light and often hilarious (I laughed out loud throughout the last third). These are women on the verge of a breakdown, and we are pretty sure they’re going to be okay. Pepa, for one, is a fighter. Even if her potential suicide keeps getting delayed by another knock at the door or another telephone call, we don’t for a second think she’s going to end her life. It’s clear all along that her intention is to confront her weak lover and make him tell her to her face that their relationship is over. She might not know it, but she doesn’t want him back; she just wants the dignity of a real breakup.

Furthermore, the tone of the film couldn’t be lighter. From the very beginning, we find ourselves in an artificial Madrid we are happy to inhabit. The sun is shining, the air is bright and open, the streets are nearly empty unless you need a taxi, in which case you need only raise your hand and the few people who are out and about are going about their day with a bounce in their step.

The prosperity, the goodness, the happy coincidences, all are deliberately heightened. As I mentioned above, Almodóvar was conscious of his freedom in post-Franco Spain, and Elvira Lindo spends a lot of time in her essay accompanying this release talking about how “the city opened up like a flower” in the 1980s, leading to other kinds of tragedies which aren’t part of this film. In the interview with him included in this Criterion edition, Almodóvar states that he wanted the film to exude freedom, a sense that the dark curtains had been lifted and light and air were flowing in. Post-Franco, he says, things were infinitely better. Sadly, though, at least one thing did not change, and its the tragedy the film deals with with a light touch: men still leave women, and in the most cowardly way.

Iván’s fortunes, though, are about to turn. He’s left a suitcase at Pepa’s home that he tries to retrieve through the picture. Any attempts spook Candela since she is always afraid the police have finally arrived to take her away. And the penthouse is soon filled with more unexpected visitors. In a grand coincidence (the film celebrates these unlikely developments with glee) Iván’s grown son, Carlos, played by a wonderfully stuttering Antonio Banderas, shows up with his fiancé, looking to lease the penthouse. Recognizing that his father is a bit of a louse, Carlos doesn’t judge Pepa for her anger, and they strike up a friendly relationship. Of course, the police do arrive, but not alone. They show up at the same time as Lucía, Carlos’s mother; she’s made her way to Pepa’s penthouse to find out just where Iván is. We learn that she spent years in a mental institution after Iván abandoned her (perhaps she’s the main character in Cocteau’s The Human Voice. Lucía seems fine now, if a bit angry to find her son consorting with Pepa.

I’m glad to have joined in the fun, and I don’t think anyone will mind if you pop over to Pepa’s penthouse. Make sure you come in time for some gazpacho!