David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

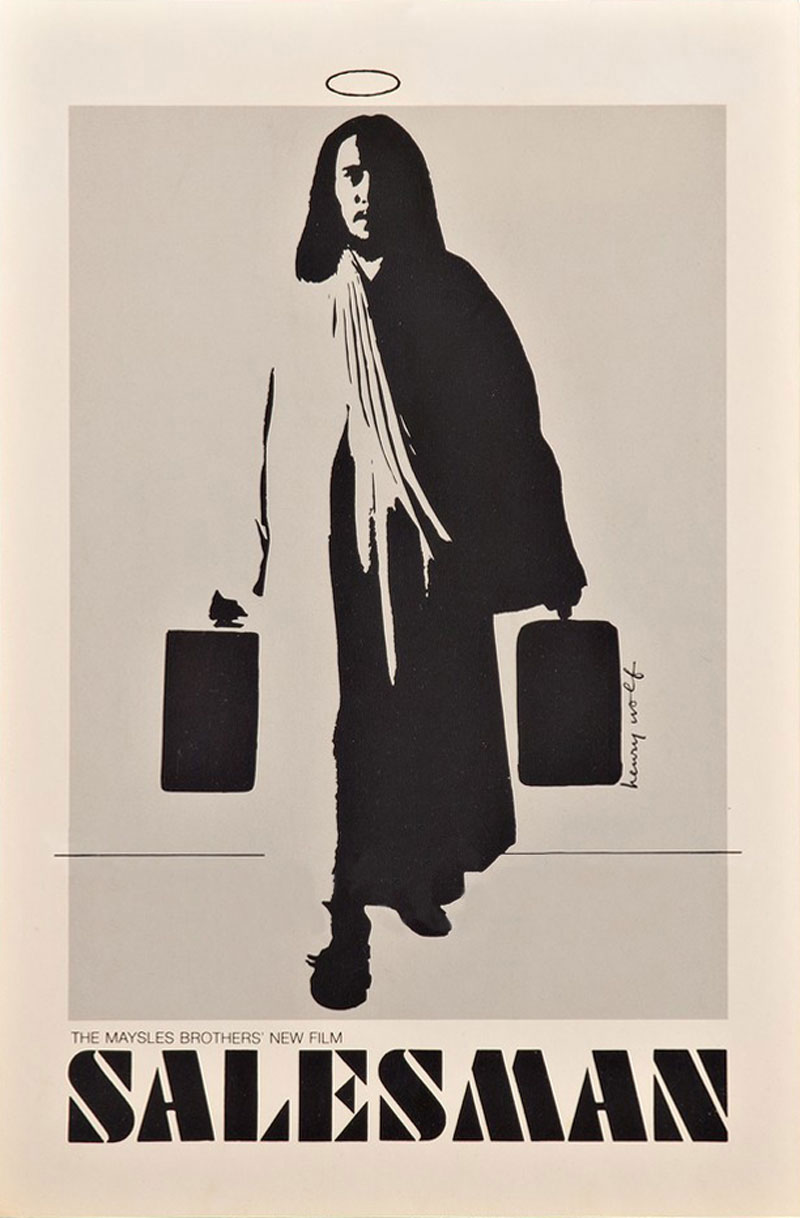

Though it’s far from sadistic or brutal, Salesman is designed to stir up a viewer’s discomfort, even to the point of outrage, with an end goal of rousing our empathy. The merciless exposure of a quartet of traveling door-to-door Bible peddlers (though they’re explicitly told to avoid thinking of themselves in such terms) strikes us as quite funny at first but gradually wears us down to a state of mournful pity as we tap into the grim desperation that pushes them forward to each new sales call, each awkward encounter with a reluctant prospect. In the early going, we’re struck by the refreshingly honest and fairly astonishing footage as we take in this unrehearsed, unscripted record of high pressure tactics used by representatives of the Mid-American Bible Company. We get a rare opportunity to view the operation from a variety of angles:

- the direct encounter between salesmen and their working-class customers in the intimate setting of private homes.

- the motivational/confrontational meetings organized by district managers tasked with ratcheting up a fresh surge of zeal within their forlorn recruits – typically middle aged white Catholic men, presumably lacking in technical or professional skills who are averse to more physically intensive forms of labor.

- the tedious hours in between pitches, generally spent in transit or in shabby hotel rooms where the men bunk up for the night, four to a room to cut down on costs.

- the awkward silences – those moments of pensive reflection in between the leverage, the small talk, the quippy banter and passive-aggressive cajoling that disguise the exploitation and resentment that seem to fuel the whole ghastly enterprise.

Salesman is a remarkable, definitive example of direct cinema that launched Albert and David Maysles, and their brilliant editor Charlotte Zwerin, into a celebrated run of great non-fiction American films over the next several decades.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

Culled from some 100 hours of footage shot in late 1966 and early 1967, Salesman provided piercing insight into the lives of ordinary people who hardly did the sort of things that normally got much cinematic attention. This was a movie about squares, uptight folks hard-pressed by the demands of economics and society to fit in, to play by the rules, to walk the straight and narrow, for the most part anyway. And a big part of their upbringing was to maintain a reliably predictable politeness that would practically oblige the occupants (most of them housewives trained to be accommodating hosts) to open the door and allow the salesman to enter their homes, where they would patiently listen to the spiel and be subjected to the resulting pressures.

The Maysles brothers had set out to film some kind of sales operation as they pooled resources to make their first feature film outside of the television documentary jobs that had earned their paychecks over the first half of the decade. They hadn’t initially set out to focus on the religious element – the product being pushed might have been anything, when the project itself was first imagined – but that Bible angle certainly made the story all the more compelling. The audience was forced to grapple with the degree to which spiritual convictions, guilt and sentimentalism all played significant roles in creating dramatic tension in a potential customer’s decision on whether or not to spend fifty or more hard-earned dollars (that’s quite a lot, in 1967 currency) on ornate gilt-edged and lavishly illustrated leather bound volumes of the Good Book. These particular editions were presented as suitable family heirlooms, but in the context of the shabby working class households that we see the salesmen visiting, it’s painfully obvious that most of the Bibles sold would have limited functional value beyond alleviating the pangs of conscience that compelled their new owners to make that commitment.

For contemporary audiences, Salesman was a revelation, one that’s easy for us to overlook after half a century of technical innovation in the cinematic arts. The efficient portability of new (relatively) lightweight cameras and tape recorders allowed David and Albert to capture familiar reality with unalloyed freshness. Unscripted scenes featuring real people speaking as themselves in ordinary circumstances, easy transitions from interiors to exteriors, and the ability to cheaply shoot dozens of hours of film in creating a rich archive of material to draw from – all these new breakthroughs also allowed for the development of a new aesthetic, where sharp focus, crisp lighting, expert framing and aural clarity were no longer prioritized or privileged as essentials of quality movie-making. A raw “warts and all” portrayal of life as we actually lived it was now possible, and this film was a provocative example of what we might be surprised to discover when we focus on the mundane.

Along the same line, cinema vérité had been making an impact throughout the decade, and was already well enough established as its own sub-genre that the Maysles specifically voiced their objections to including their film among its ranks. They preferred the term “direct cinema.” The dispute nowadays feels more semantic than substantial, but I guess the distinction provided some separation with European innovators like Jean Rouch (Chronicle of a Summer) aligned the Maysles brothers with filmmakers like Robert Drew and D.A. Pennebaker, with whom they worked on the documentaries about John F. Kennedy just recently released by the Criterion Collection. (And I guess it’s also important to mention that Allan King’s Actuality Dramas were apparently something different altogether!)

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

I’ve watched Salesman several times over the years, generally with rapt fascination as I surf the emotional wave of sarcasm, bemusement and pathos that the Maysles and Zwerin construct here. As my familiarity increased, the strategic importance of so many editing decision has become more clear and obvious. Scenes where “nothing happens” on screen are placed with excruciating precision, silent punctuation marks that bring us into a squirming communion with sad lost souls. I’ve watched it with friends and family, and all by myself, just to reconnect with a cultural realm so redolent of the environments in which I grew up. Everyone smoked, the cars were massive. Relationships between friends, spouses, sales reps and customers were deprecating all around. The men seem weighed down by burdens of fatigue and cynicism, and the women seem stunted and trivial from the limited options of education and empowerment made available to them.

It’s a grey, grim world, with little if any hope of lasting reprieve from the dog-eat-dog consumerism gnawing at the psyches of its forlorn inhabitants. The feeble attempts at bravado, camaraderie and mutual encouragement don’t come across as disingenuous as much as they feel like last-gasp efforts to breath some life into a grinding ordeal that’s slowly running out of steam. I suppose a charge could be brought against Salesman that it’s somewhat cruel to bring such dismal exchanges to the surface, forcing us to pay attention and notice these people who might otherwise spiral off into anonymous oblivion, content in their self-induced delusions of a life well lived.

I actually give the film credit for the role it presumably played in drawing down the curtain on that era of door-to-door hucksterism. I still receive the occasional cold-caller earnestly knocking on my front porch, typically to inquire about home repairs or wanting to make sure that we’re getting the best deal possible on our natural gas supply. But such an approach is usually considered rather intrusive and probably not all that effective either. For this, and for establishing the Maysles as a cultural force to be reckoned with in cinema and beyond, I’m happy to give Salesman a strong endorsement. It comes in Criterion Green, or Masters of Cinema White, which I refer to as the Antique Gold. Now which color would look best on the coffee table in your living room?

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

Christian Science Monitor (interview with Albertr Maysles)

Previously: 2001: A Space Odyssey

Next: Capricious Summer