David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

Capricious Summer is fairly easy to watch (a slight 76 minute feature, in color), summarize (a whimsical sex comedy about three middle-aged men in a small rustic town are shaken out of their routines when they’re distracted by the arrival of an itinerant magician and his beautiful assistant) and compartmentalize (coming at the tail end of the Czech New Wave, this is Jiří Menzel’s less celebrated follow-up to the Oscar-winning Closely Watched Trains.) But just as conveniently as the film might fit within those pigeonholes, there’s a serious risk of underestimating what Menzel places before us here.

Comfortably nestled within a volume of the Eclipse Series expressly dedicated to the aforementioned Czech New Wave, Capricious Summer is at risk of being regarded as simply one of six quirky, enjoyable treats in that box. Each film has its own distinctive feel, flavor and lasting impression, but in commercial terms, they’re altogether too obscure to warrant their own individual releases outside of the curated sets that Eclipse specializes in. This particular title is probably my second favorite in the set (behind the incredible Daisies), one that I enjoyed watching as a man in a similar stage of life as the protagonists. I relished the opportunity to have a few hearty laughs at the expense of fellows who seem a bit more forlorn and confused at this stage of their journey than I tend to think I am myself. I’m not sure how it would come across to viewers who have not yet acclimated themselves to Czech film – it’s probably advisable to go with the more popular Milos Forman films from this era (Loves of a Blonde or The Fireman’s Ball) as an entry point – but once you’re over that hurdle, Capricious Summer is nicely accessible.

It also holds up well under closer scrutiny, as I’ve recently discovered through some conversation with my online friend and occasional podcasting partner (over on FlixWise) Martin Kessler, a filmmaker now based in Toronto but with deep personal and family roots in what is now the Czech Republic. Our correspondence by email is quoted below.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

It will take a bit of reading to get to the specific response to that section header about how Capricious Summer was received by its initial audience, but for starters, it’s crucial to point out that the film was released in May 1968, quite a significant reference point in Czech and Slovak history. Smack dab in the middle of the Prague Spring, one of numerous cultural and political flashpoints in that incredibly tumultuous year. So with that brief preamble, let’s get into the conversation between me and Martin. I’ll italicize his words, and publish mine in plain text…

Just to get things started, I want to reference a comment you recently made on Twitter in response to Aaron West, where you said the dialogue in Capricious Summer was “like poetry” to the point where you thought it might be difficult to translate, or at least that something might be lost. Could you elaborate on that? With your knowledge of the original language and cultural context, perhaps there are some insights you can pass along to English-speaking viewers.

Yeah, the dialogue has a poetic (or maybe lyrical is a better way to describe it) quality. Part of it comes from evoking the way people wrote/spoke in that time period in which Capricious Summer is set: the 1920s, between the two wars. It sounds old fashioned, there are some words and phrases you wouldn’t hear spoken today, and has some typically Czech word play. I haven’t read the story it was based on, but I believe Vladislav Vančura wrote mostly in dialogue, almost like a playwright. He also wrote the story that Marketa Lazarová is based on, which also has highly stylized dialogue. I don’t know if any of Vančura’s work has been translated into English. I think he may have also made films, but between Nazi and Communist censorship, I’m not sure any of them still exist.

I watched Capricious Summer again last night, to track with what you’re saying by intentionally tuning my ear to the sound and rhythms of the voices. I could definitely pick up on some rhetorical flourishes, some deliberate cadence that seemed like it was meant to evoke a certain mood, or perhaps an era. At times, it felt like the actors were reciting a finely wrought script, with earthy overtones and sardonic accents to be sure, but words precisely chosen nevertheless. I’m surprised to discover the link between this film and Marketa Lazarová – maybe I missed that, or have just forgotten about it in the interval since I reviewed that incredible film last year.

I don’t think I saw anyone mention the connection to Marketa Lazarová when either was released by Criterion. There have been other films adapted from Vančura’s writing too. Another pretty well-known one is Luk Královny Dorotky (The Bow of Queen Dorothy), which is by the same filmmaker who adapted End of August At the Hotel Ozone, and I think works almost like an anthology film with three stories.

From a more personal perspective, I feel like the film captures some essentially Czech values, especially regarding sexuality and good humour over things like piety, commerce, and patriotism. There’s some overlap with Švejk-ism in how the ex-soldier is treated. I’ve seen it characterized as a light sex-comedy, but I think that betrays the film’s political and cultural context. Like for instance that the story was set in really the only period in 400 years that it had been a free country (until 1989), and the film was made and released at a time when people were not free. That element of the film was quite powerful to people who saw it on its initial release, including my father who would have been 15 or 16 when he saw it. I know he also took his grandfather (who had lived through the period the film was set in) to see it, and supposedly it was the only film aside from Winnetou he had seen in something like 35 years. I was told that my great-grandfather was quite moved by it though slightly embarrassed that one of the actors showed his rear end.

This historic background context is wonderfully valuable and informative to me. I think I recognized that there was a lot more than “light sex comedy” going on here, even though it is fun and easy to laugh at the plight of middle-aged men coming into contact with the realization of a fantasy and then not being all that able to uphold their end of the bargain! But imagining what this film would have meant to Czech viewers of 1968, in the midst of a very tumultuous and unpredictable political crisis, opens up new avenues of reflection on the film. I also find myself surprisingly affected by the account of your great-grandfather who found his way to watch this film as a rare special occasion. I suppose I can understand his abashed response to the brief flash of bare male ass in that early scene, given the ethos of his times. But was he similarly discomforted by the sight of Jana Preissova’s side boob? ;)

Philip Kaufman’s audio commentary for the Unbearable Lightness of Being relates a good understanding of the context for that period in Czech history when Capricious Summer was released. He explained about how sexuality and humour functioned as rebellious acts during that time. I know for Capricious Summer and its like, people unfamiliar with Czech culture often don’t pick up on the political dimension woven into the aesthetics of the film. In contrast to the sort of social-realist heavy handed message films that were pushed by the communist regime, the so-called ‘Films about nothing’ were quite bold in their depictions of life.

It’s been several years since I watched The Unbearable Lightness of Being. I meant to get to it after Trevor and I did our podcast on the Pearls of the Czech New Wave set last summer. This conversation rekindles my sense of urgency! I have been listening to an audiobook titled 1968: The Year That Rocked The World, that goes into quite a bit of detail about the many historic upheavals of that year, including Dubcek’s efforts at reform, the Prague Spring and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. I can’t say that I’ve mastered all the details of what went on at the time, but the narrative certainly paints a vibrant, dynamic and ultimately tragic picture of what the Czechs and Slovaks had to endure. Plugging Capricious Summer‘s irreverent, mildly satirical humor into that setting definitely enhances my admiration for what Menzel accomplished in this seemingly slight exercise.

I wish I had a better knowledge of poetic devices so I could say which were being specifically used, but I think it’s that combination of period, poetry, and humour that would be difficult to translate. I haven’t seen it commented on, so it’s maybe a bit too bad that that atmosphere the dialogue contributes to, of being in the eye of a historical storm, is lost. I don’t know how an English translation might give it that nuance or quality without coming across as stuffy or clunky or whatever.

Especially since the translation can only be text on the screen, which mostly fails to capture the nuances of voice tone and tempo built into the script. I suppose that it will have to be sufficient to just draw a viewer’s attention to this characteristic of the dialog so that, as was the case in my most recent viewing, we can at least listen to the sound and cadence of the voices. Without understanding a word that was spoken, I was at least able to recognize a certain lyricism and poetic attitude that came through in the conversations.

The film Kolya, which won a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in the 1990s, had a joke that played on the word for ‘beautiful’ in Czech and the world for ‘red’ in Russian, but I don’t think there’s any way that could be translated to English. I’m not sure how that was handled.

Capricious Summer‘s comic-political element of lustful and somewhat powerful older men being ground to a halt by young women was pretty common. You see it in Daisies, with the two girls having men buy them dinner and ditching them on the train. Or in both of the Miloš Forman films that Criterion has released. There are a bunch of other examples in great Czech films. It’s really too bad how few of them have been released in North America.

The examples you cite are all quite enjoyable and it’s definitely illuminating to see them lined up like that as case studies in humor directed at men in the declining phases of their virility! It’s a timeless source of amusement, and a bittersweet opportunity to have a laugh at their (and in some cases, our own) expense!

Here is a photograph of my great grandfather (with his mother) from around the time Capricious Summer takes place:

What an extraordinary portrait!

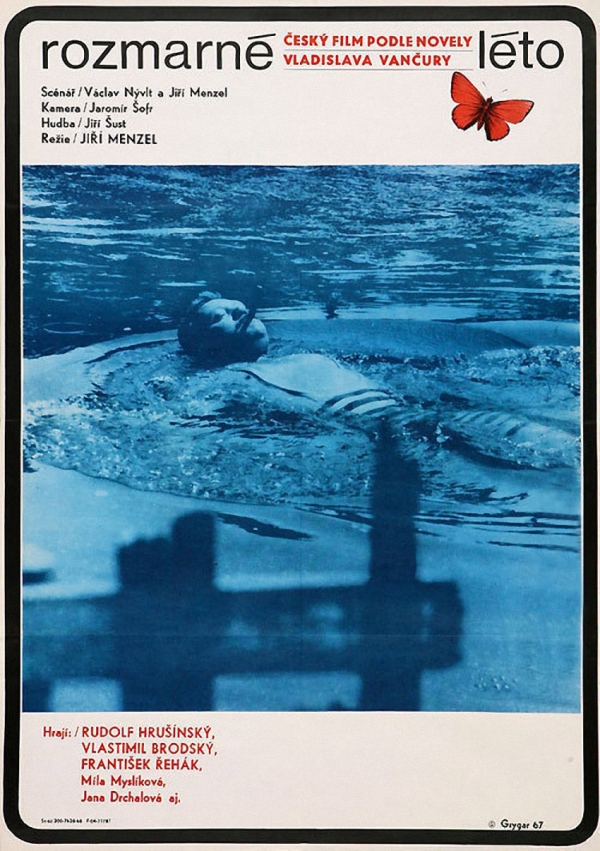

That poster for the film (at the top of this post) is interesting. The red text at the top specifically advertises it as a Czech film based on Vančura’s novel, and draws more attention to that than anything else. I’d guess it was a selling point for the film when it was first released.

A printed quote at the beginning of the film and the opening credits also seem to emphasize the connection to Vančura, either as an assumption that the name is meaningful to contemporary viewers, or as an endorsement to become more familiar with his work.

I don’t know if it’s too much of a culture jump, but last time around watching Capricious Summer, in a roundabout way it reminded me of Japanese Ukiyo-E artwork, depicting the beauty of impermanence, the ‘floating world’, and the colourful, peaceful scenes of everyday life. But I think maybe there’s some similarity in Capricious Summer’s ‘rained yesterday and will rain tomorrow’ sense of ethereal impermanent beauty. Again going back to the context the film was made in, the story really is just this wafer-thin slice of whimsy in between mountains of turmoil. There’s a weight to its nuanced language, the breezy thoughtfulness, the humour, the free sexuality, the rich food. There’s a melancholy that comes with beauty that’s so carefree and fleeting.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Besides these recent ruminations, I’ve also written (in 2012) and podcasted (in 2015) about this film. The links embedded in that sentence will give you access to that information. As for now, I think the dialog above adequately sums up my current take on the film. So let me say, thank you so much Martin for this extraordinary background information and personal account of what Capricious Summer means to you! I’ll never watch this film again without thinking about what you’ve shared.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Director page for Jiří Menzel on Central Europe Review

- Guardian interview (2008) with Menzel by Steve Rose

- The Ceremony of the Everyday (career recap) on Central Europe Review

- Filmmaker Magazine interview (2008) by Nick Dawson

- A Common Reader (review)

- dcpfilm review by anonymous

- E Street Film Society review by Daniel Barnes

- Expats.cz review by Jason Pirodsky

Previously: Salesman

Next: Rosemary’s Baby